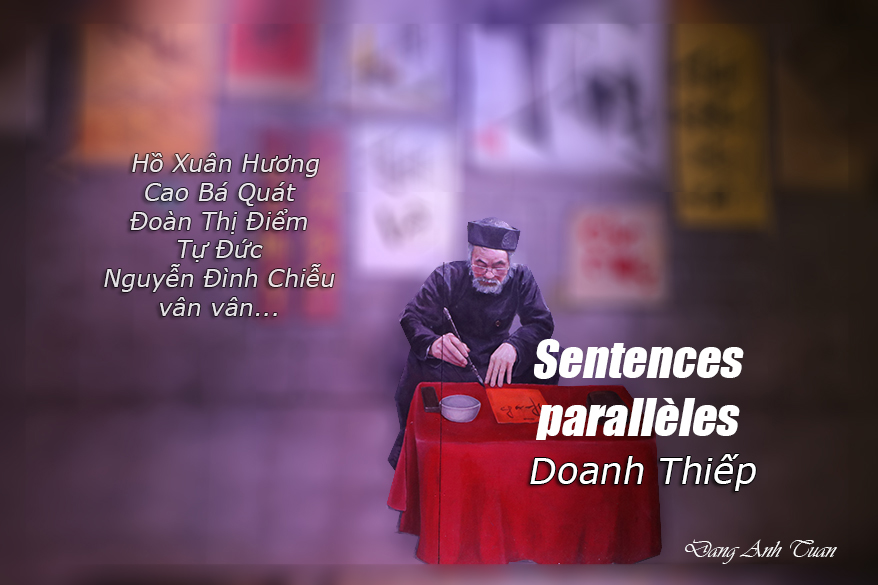

Doanh thiếp

Version vietnamienne

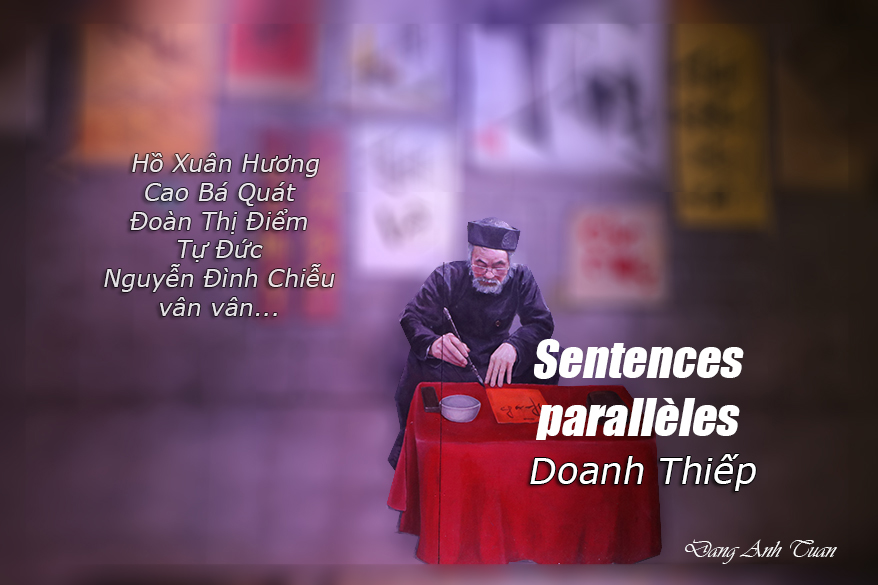

L’un des charmes de la poésie vietnamienne réside dans l’utilisation des sentences parallèles. On y trouve non seulement l’antithèse des significations ou des mots employés mais aussi la pertinence dans la pratique de ces sentences. C’est pourquoi les sentences parallèles constituent l’une des difficultés majeures pour les novices mais elles deviennent néanmoins l’un des attraits incontestables pour les poètes vietnamiens connus comme Hồ Xuân Hương, Tự Ðức, Cao Bá Quát, Ðoàn Thị Ðiểm, Nguyễn Ðình Chiễu etc …

Ceux-ci ont eu l’occasion de les utiliser savamment. Ils nous ont légué des sentences dignes de leur talent inouï et servant toujours de référence dans la poésie vietnamienne. Grâce à l’antinomie trouvée dans les mots ou les significations à l’intérieur d’un vers ou de strophe en strophe, le poète réussit à faire ressortir une raison ou une critique et à renforcer la vigueur de sa pensée. Les sentences sont composées à partir des règles prosodiques établies essentiellement sur l’alternance des tons bằng et trắc (1) tout en s’appuyant sur la puissance des combinaisons des mots utilisée de manière harmonieuse et accrue par l’extrême musicalité de la langue vietnamienne et sur l’antithèse des significations (ou d’idées) ou la cohérence et la mise en corrélation des significations.

Les sentences parallèles constituent en quelque sorte un passe-temps intellectuel, un art dont les poètes de grand renom ne peuvent pas se passer. Ces derniers ont réussi à l’exercer avec une facilité étonnante et une ingéniosité remarquable. Les sentences parallèles reflètent exactement ce que le poète a vu et ressenti dans la vie quotidienne.

Rien n’est étonnant de voir l’engouement des Vietnamiens pour cette prosodie subtile au fil des générations. Elle devient non seulement le plaisir du peuple mais aussi une arme aussi efficace contre l’obscurantisme, l’oppression et la provocation.

Thịt mỡ, dưa hành câu đối đỏ,

Cây nêu, tràng pháo, bánh chưng xanh

Viande grasse, légumes salés, sentences parallèles rouges,

Mât du Tết, chapelets de pétards, gâteaux de riz du nouvel an.

Les sentences parallèles font partie de ce que chacun des Vietnamiens ne peut pas manquer à l’occasion de la fête du Tết. Elles témoignent de la familiarité et de l’attachement profond que le Vietnamien aime réserver à cette prosodie populaire lors du nouvel an. Riche ou pauvre, poète ou non, chacun tente d’avoir ces sentences pour les déposer devant l’autel des ancêtres ou pour les accrocher à l’entrée de sa maison. Il les compose lui-même ou se procure auprès des lettrés celles qui formulent le mieux ses aspirations personnelles.

Les sentences parallèles trouvent probablement leur origine dans la littérature chinoise et sont connues en vietnamien sous le nom « Doanh thiếp (2) » . Elles comprennent deux vers: l’un est appelé le vers supérieur (vế trên) et l’autre le vers inférieur (vế dưới). Le vers supérieur est le vers composé et proposé par une personne souhaitant le commencement des sentences tandis que le vers inférieur est celui qu’une autre personne veut terminer pour la réplique.

On trouve quelques caractéristiques communes à ces deux vers:

– Le nombre de mots doit y être le même.

– Le contenu doit y être convenable au niveau de la signification quand il s’agit de l’antithèse ou de la cohérence des idées.

– La forme doit y être respectée quand il s’agit de l’opposition totale des mots employés (respect de l’ordre de l’emplacement des mots, des adjectifs et des verbes, observation des règles d’opposition des registres sonores bằng et trắc).

Dans l’exemple cité ci-dessous,

Gia bần tri hiếu tử

Quốc loạn thức trung thần.

Nhà nghèo mới biết con hiếu thảo

Nước loạn mới biết rõ tôi trung

La famille pauvre discerne des enfants pieux

Le pays en désordre reconnaît des sujets fidèles.

on constate qu’il y a le même nombre de mots (5 mots dans chaque vers), le parallélisme des idées et l’observation stricte des registres sonores bằng et trắc employés dans les deux vers. A la place du ton bằng (nghèo) du vers supérieur on retrouve un ton trắc (loạn) au même emplacement dans le vers inférieur. De même, les tons trắc restants du vers supérieur hiếu et tử sont remplacés respectivement par les deux tons bằng trung et thần dans le vers inférieur.

Les sentences parallèles constituées de un à sept mots pour chacun des vers s’appellent des petites sentences parallèles (ou tiểu đối en vietnamien). Lorsqu’elles contiennent plus de sept mots et suivent les règles prosodiques de la poésie, on les désigne sous le nom de « sentences parallèles poétiques » (ou thi đối). C’est le cas de l’exemple cité ci-dessus. En cas du parallélisme d’idées, on les appelle câu đối xuôi en vietnamien. Dans ce cas, aucune opposition d’idées n’y est décelée. Par contre, il y a une cohérence et une corrélation entre leurs deux vers, c’est ce qu’on trouve dans ces deux sentences suivantes:

Vũ vô kiềm tỏa năng lưu khách

Sắc bất ba đào dị nịch nhân.

Sans avoir la serrure à la porte, la pluie peut retenir celui qui est pressé de partir

Sans la possibilité de faire les vagues de la mer, la beauté d’une fille peut noyer celui qui s’en est épris.

Dans le cas contraire, on les appelle câu đối ngược en vietnamien. Dans ce type de sentences, l’antinomie de significations ou d’idées est visible dans les deux vers. C’est le cas de l’exemple suivant:

Hữu duyên thiên lý năng tương ngộ

Vô duyên đối diện bất tương phùng

Có duyên dù ở xa ngàn dậm cũng có thể gặp nhau

Còn không có duyên rồi dù ở có đối mặt cũng không gặp được nhau.

Malgré plusieurs milliers de kilomètres de distance, on peut se rencontrer lorsqu’on a la chance.

En dépit de la proximité géographique, on ne peut pas se voir lorsqu’on n’a pas la chance.

Les sentences parallèles sont employées fréquemment par le poète Cao Bá Quát. Il y a eu une anecdote sur lui lors du passage de l’empereur Minh Mạng dans son village quand il était encore un jeune garçon entêté. Au lieu de se cacher, il se jeta dans un étang pour prendre une baignade. Devant son attitude absurde, il fut ligoté et emmené devant Minh Mạng sous un soleil accablant. Surpris par sa hardiesse et son jeune âge, celui-ci lui proposa de le libérer à condition qu’il réussît à composer une sentence appropriée répondant à celle émise par l’empereur. En voyant la poursuite engagée par le plus gros poisson sur le petit dans l’étang, l’empereur commença à dire:

Nước trong leo lẽo, cá đóp cá

L’eau étant tellement limpide, le grand happe le petit.

Sans hésitation, Cao Bá Quát répliqua avec une facilité étonnante:

Trời nắng chan chan, người trói người

Le soleil étant tellement accablant, le grand ligote le petit.

Émerveillé par sa promptitude et par son talent inouï, l’empereur fut obligé de lui rendre la liberté. Cao Bá Quát, connu pour son indépendance, sa présomption et son mépris à l’égard du système mandarinal, était obligé de relever souvent le défi lancé par ses adversaires. Un beau jour, profitant de sa participation à un exposé organisé par un mandarin sur la poésie, il ne cessa pas de faire le clown lorsque ce dernier continua à donner des explications simplistes sur les questions posées par le public. Énervé par sa provocation continue, le mandarin fut obligé de le défier dans l’intention de le punir immédiatement en lui demandant de donner une sentence appropriée répondant à celle émise par lui-même :

Nhi tiểu sinh hà cứ đác lai, cảm thuyết Trình, Chu sự nghiệp

Mầy là gả học trò ở đâu đến mà dám nói đến sự nghiệp của Trương Công và Chu Công?

Étant un élève venant de quel coin, oses-tu citer les œuvres de Trương Công et Chu Công?

Sans hésitation, il lui répondit avec impertinence:

Ngã quân tử kiên cơ nhi tác, dục ai Nghiêu Thuấn quân dân

Ta là bậc quân tử, thấy cơ mà dấy, muốn làm vua dân trở nên vua dân đời vua Nghiêu vua Thuấn.

Etant un homme de ren (3), profitant des moments opportuns pour m’élever, puis-je devenir roi à l’image des rois Nghiêu et Thuấn?

Les sentences parallèles constituaient autrefois un lieu de prédilection où les Chinois et les Vietnamiens aimaient s’affronter publiquement. La sentence répondante du lettré Giang Văn Minh, ancrée dans la mémoire de tout un peuple et perpétuée depuis plusieurs générations :

Ðằng giang tự cổ huyết do hồng.

Le fleuve Bạch Ðằng continue à être teinté avec du sang rouge.

illustre bien sa détermination infaillible face à la provocation de l’empereur des Ming avec sa sentence émise suivante:

Ðồng trụ chí kim đài dĩ lục.

Le pilier en bronze continue à être envahi par la mousse verte.

Il y a aussi des poètes anonymes qui nous ont laissé des sentences parallèles mémorables. C’est celles qu’on a trouvées sur l’autel du héros national Nguyễn Biểu dans la commune Bình Hồ au Nord Vietnam.

Năng diệm nhơn đầu năng diệm Phụ

Thượng tồn ngô thiệt thượng tôn Trần

Ăn được đầu người thì có thể ăn cả Trương Phụ

Còn lưỡi của ta thì còn nhà Trần

En mangeant la tête humaine, on peut manger aussi Trương Phụ

En ayant encore la langue, je peux survivre autant que la dynastie des Trần.

Grâce à ses deux sentences, le poète anonyme a voulu rendre un vibrant hommage au héros national. Celui-ci fut noyé par le généralissime chinois Trương Phụ après que ce dernier avait organisé un banquet somptueux en son honneur. Pour intimider Nguyễn Biểu, Trương Phụ n’hésita pas à lui présenter un plat où on trouvait la tête décapitée d’un adversaire. Au lieu d’être effrayé par cette présentation, Nguyễn Biểu restant impassible, se servit des baguettes pour déloger les yeux et les mangea savoureusement.

Lors de la chute de Saigon en 1975, un anonyme a composé les deux sentences parallèles suivantes:

Nam Kì Khởi Nghĩa tiêu Công Lý

Ðồng Khởi vùng lên mất Tự Do.

Le soulèvement du Sud anéantit la justice

La révolte en marche fait périr la liberté

car les noms des boulevards Công Lý et Tự Do ont été remplacés respectivement par Nam Kì Khởi Nghĩa et Ðổng Khởi dans la ville bouillonnante du Sud. C’est par le biais de ces sentences que le poète anonyme a voulu mettre en relief sa critique acerbe à l’égard du régime.

Profitant de la subtilité trouvée dans les sentences parallèles et du sens figuré dans la langue vietnamienne, les hommes politiques vietnamiens, en particulier l’empereur Duy Tân, ont eu l’occasion de s’en servir souvent pour sonder ou ironiser sur l’adversaire. Caressé par l’idée de fomenter depuis longtemps une insurrection contre les autorités coloniales, Duy Tân, profitant de l’excursion maritime qu’il a effectuée avec le premier ministre Nguyễn Hữu Bài à la plage Cửa Tùng (Quảng Trị), proposa à ce dernier de lui donner une réplique appropriée à sa sentence émise:

Ngồi trên nước không ngăn được nước

Trót buôn câu đã lỡ phải lần

Etant assis sur l’eau, on est incapable de la retenir

En commettant l’erreur de jeter l’appât, on n’a plus la possibilité de le retirer.

À travers ces deux sentences, Duy Tân voulut connaître l’intention politique de son ministre Nguyễn Hữu Bài car le mot « nước » en vietnamien désigne à la fois l’eau et le pays. Il aimerait savoir si ce dernier était de son avis ou à la solde des colonialistes français. Connaissant la conjoncture politique et étant un proche des autorités coloniales, Nguyễn Hữu Bài préféra l’immobilisme et adopta une politique de concertation en donnant la réplique suivante:

Ngẫm việc đời mà ngán cho đời

Liệu nhắm mắt đến đâu hay đó

En réfléchissant mûrement sur la vie, on en est dégoûté.

En tentant de fermer les yeux, on n’a qu’à attendre le moment propice.

Étant chargé de juger le tort de Ngô Thời Nhiệm d’être le partisan de l’empereur Quang Trung, Ðặng Trần Thường l’a défié en émettant la sentence suivante:

Thế Chiến Quốc, thế Xuân Thu, gặp thời thế, thế thời phải thế,

À l’époque des Royaumes Combattants ou des Printemps Automnes, quiconque rencontrant le moment opportun, en profite pour devenir celui qu’il est.

Ngô Thời Nhiệm a réussi à donner sa sentence répliquante avec ironie à Ðặng Trần Thường, un partisan de l’empereur Gia Long:

Ai Công hầu, ai Khanh tướng, trên trần ai, ai dễ biết ai

On est duc et marquis ou mandarin et ministre; quiconque vivant dans cette société, distingue facilement le rôle que chacun assume.

Il réussit à montrer non seulement sa bravoure mais aussi son mépris à l’égard des gens arrivistes comme Ðặng Trần Thường. Irrité par ces propos vexants, ce dernier donna l’ordre à ses subordonnés de le fouetter à mort devant le temple de la littérature. Ngô Thời Nhiệm n’a pas eu tort de rappeler à Ðặng Trần Thường cette remarque car il fut condamné à mort plus tard par l’empereur Gia Long.

Phu’, c’est le nom en vietnamien qu’on attribue aux sentences parallèles ayant un grand nombre de membres de phrases. C’est le cas de l’exemple de sentences employées par Ngô Thời Nhiêm et Ðặng Trần Thường. Lorsque celles-ci comprennent trois ou plus (dans l’exemple cité ci-dessus) de membres, au milieu desquels on insère un membre très court, on les appelle sous le nom phú gối hạc (la rotule de la grue) en vietnamien car on trouve une ressemblance avec le schéma de la patte de la grue avec les deux membres longs séparés par la rotule.

Ces sentences parallèles deviennent au fil des années l’expression populaire véridique de tout un peuple en lutte permanente contre l’obscurantisme et l’oppression. En donnant à ce dernier l’occasion de montrer son caractère, son tempérament et son âme, elles réussissent à justifier ce que la romancière Staël a l’occasion de dire: En apprenant la prosodie d’une langue, on entre intimement dans l’esprit de la nation qui la parle. C’est avec ces sentences parallèles qu’on peut comprendre et sentir mieux le Vietnam. On serait alors plus proche de son peuple et de sa culture.

(1) bằng deux accents: accent grave et sans accents ; trắc: 4 accents: accent retombant, tilde, accent aigu et accent intensif.

(2) Doanh thiếp: manuscrit accroché au poteau de la maison.

(3) Être ren: c’est savoir faire régner bonne foi, tolérance, diligence et générosité.

![]()