The emergence of the Thai people is only strengthened since the XIVth century. Nevertheless it is a very ancient people of Southern China. It is a member of the Austro-Asiatic group (Chủng Nam Á) (or Baiyue or Bách Việt in Vietnamese). It is this group French archaeologist Bernard Groslier often indicated under the name of « Thai-Vietnamese group ».

Repulsed by the Tsin of Shi Huang Di, the Thai people try to resist again and again. For Vietnamese writer Bình Nguyên Lôc, the subjects of Shu and Ba (Ba Thục) kingdoms annexed very early by the Tsin in the Szechuan (Tứ Xuyên) (1), were the Proto-Thai (or Tày). According to this writer, they belonged to the Austroasiatic group of branch Âu (or Ngu in language mường or Ngê U in Chinese mandarin (quan thoại)) to which the Thai and the Tày were attached.

For him as for other Vietnamese researchers Trần Ngọc Thêm, Nguyễn Đình Khoa, Hà Văn Tấn etc .., the Austro-Asiatic group contains 4 different subgroups: subgroup Môn-Khmer, subgroup Việt Mường (branch Lạc), subgroup Tày-Thái (branch Âu) and subgroup Mèo-Dao to which it is necessary to add the subgroup Cham, Raglai, Êdê to define the Indonesian race (or Proto-Malay) (2) (Chủng cổ Mã Lai).

The contribution of the Thai people in the foundation of the Ậu Lạc kingdom of Thục Phán (An Dương Vương) is no longer in doubt after the latter managed to eliminate last king Hùng of the Văn Lang kingdom because the name « Âu Lạc » (or Ngeou Lo) evoke obviously the union of two ethnic groups Yue of branch Âu (Proto-Thai) and branch Lạc (Proto-Viet ). Furthermore, Thục Phán originating from the royal family of Shu (Thục), an Yue of Thai branch, which shows at such a point the union and the common fate of these two ethnic groups in front of the Chinese expansion.

It is what is has been reported in Chinese historical writings ( as Kiao -tcheou wai-yu ki or Kouang-tcheou ki) but it has been refuted by some Vietnamese historians because the Shu kingdom was too far the Văn Lang kingdom. This latter has been annexed very early ( more than a half century before the foundation of the Văn Lang kingdom) by the Tsin. But according to Bình Nguyên Lộc writer, in the compagny of his trusted friends, Thục Phán having lost his homeland, was forced to seek refuge at this time in the country having the same ethnic affinity, that is to say Si Ngeou (Tây Âu) located beside the Văng Lang kingdom of the Vietnamese. Furthermore, the Chinese have no interest in falsifying history by reporting that the ruler of the Âu Lạc kingdom was the Shu prince. For this latter and his trusted friends, the requests for asylum need a certain time, which explains at least a half century in this exodus before the foundation of his Âu Lạc kingdom. Moreover, he was at the head of an army of 30.000 soldiers. It is impossible for him to assure all logistical aspects and render his army invisible during the exodus by crossing through Yunan mountainous regions administered by others ethnic ennemies or people close to the Chinese. It is likely that he needed what is necessary before his conquest with Si Ngeou people (or Proto-Thaïs). Despite the legend of the Vietnamese magic crossbow, An Dương Vương (Ngan-yang wang) was a historical personage. The discovery of his capital archeological remains (Cổ Loa, huyện Đông An, Hànội ) does not question the existence of this kingdom established about three centuries before Jesus Christ. This one was later annexed by Zhao To (Triệu Đà), founder of the Nan Yue kingdom.

A long common history with the Vietnamese.

The Lạc Long Quân-Âu Cơ myth insinuate so skilfully the union and the separation of two Yue ethnic groups, one being of Lạc branch (the Proto-Vietnamese) coming down to the plains by the pursuit of water courses and rivers, the other (the Proto-Thaïs) taking refuge in mountainous areas. There are the Mường in this exodus. Being close to the Vietnamese at the linguistic level, the Mường have managed to keep their ancestral customs because they were sent away and protected in high mountains. They had a social organization similar to that of the Tày and the Thaïs.

Located in Kouang Tong (Quãng Đông) and Kouang Si (Quãng Tây) provinces, the Si Ngeou (Tây Âu) kingdom is none other than the land of the Proto-Thaïs (Thai ancestors). It is here that Shu prince Thục Phán took refuge before the Văn Lang kingdom conquest. It should also be remembered that Chinese emperor Shi Houang Di had to mobilize at this time more than 500.000 soldiers for the Si Ngeou kingdom conquest after having successfully defeated the Chu kingdom (Sỡ Quốc) army with 600.000 soldiers. You have to think that in addition to the implacable resistance of its warriors, the Si Ngeou kingdom should be very large and densely populated for the commitment of the substantial military force from Shi Houang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng).

Despite the premature death of Si Ngeou king named Yi-Hiu-Song (Dịch Hu Tống),the resistance led by the Yue of Thai branch or (Si Ngeou)(Tây Âu) succeeded in obtaining a few expected results in Southern Kouang Si with the death of general T’ou Tsiu (Uất Đồ Thư) leading a Chinese army of 500.000 men, which has been mentioned in Master Houa-nan annals (or Houai–nan –tseu in Chinese or Hoài Nam Tử in Vietnamese) written by Liu An (Lưu An), grandson of Kao-Tsou emperor (or Liu Bang), founder of Han dynasty between 164 and 173 before our era. Si Ngeou was known for the courage of its formidable warriors. This corresponds exactly to the temperament of the Thai living in the past, described by French writer and photographer Alfred Raquez:(3)

Being belligerent and adventure racer, the old-time Thai were almost constantly at war with their neighbours and often saw their successfull excursions. After each victorious campaign, the prisoners were taken with them and deported in a part of Siam territory as far away as possible from their countries of origin.

After the disappearance of this kingdom and that of Âu Lạc, the Proto-Thaï remaining in Vietnam at this time under the bosom of Zhao To (a former general of Tsin dynasty who later became the first emperor of Nan Yue kingdom) had their descendants forming properly today the ethnic minority Tày of Vietnam. Other Proto-Thaï fled to Yunnan where they united at the eighth century in Nanzhao kingdom (Nam Chiếu) then Dali (Đại Lý) where buddhism of Greater Vehicle began to take root. Unfortunaly, their attempt was in vain. Shu, Ba, Si Ngeou, Âu Lạc (5), Nan Zhao, Dali countries are part of the list of kingdoms annexed one after the other by the Chinese during their exodus. In these countries submitted, the Proto-Thaïs presence was very important. In front of the Chinese continous pressure and the Himalaya inexorable barrier, the Proto-Thaï had to get back in the Indochinese peninsular (4) by penetrating slowly like a fan in Laos, northwest region of Vietnam (Tây Bắc), northern Thailand and Upper Burma.

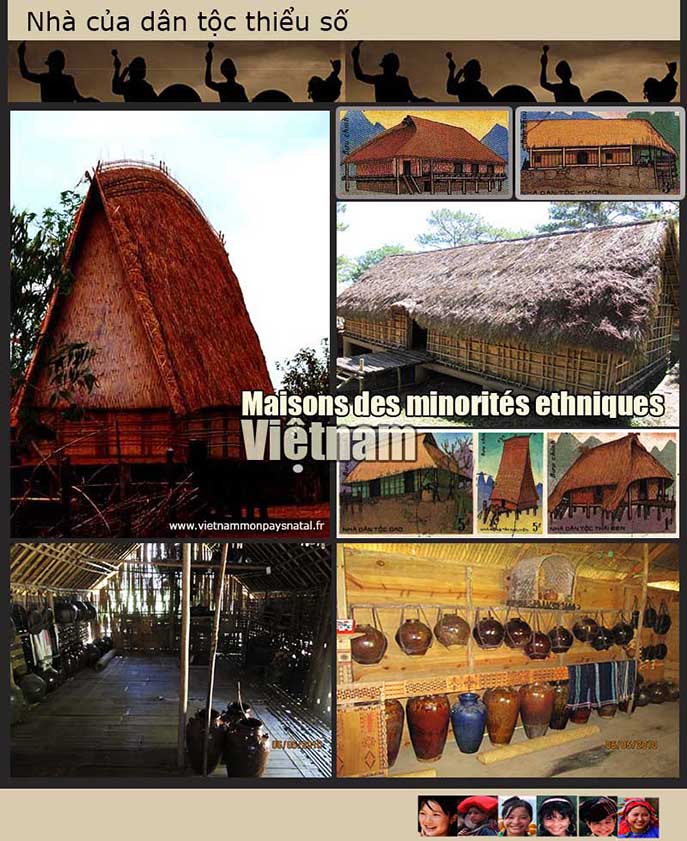

According to Thai historical inscriptions found in Vietnam, there are three important waves of migration initiated by the Thai of Yunnan in northwest of Vietnam during the 9th and 11th centuries. This corresponds exactly to the period where Nanzhao was annexed by Dali destroyed, in turn, three centuries later by Kubilai Khan Mongols in China. During this penetration, the Proto-Thaïs were separated into groups: the Thaï of Vietnam, the Thaï in Burma (or Shans), the Thaï in Laos (or Ai Lao in Vietnamese) and the Thaï in Northern Thailand. Each of these groups began to adopt the religion of these host countries. The Thaï of Vietnam do not have the same religion as those of other territories. They continue to keep animism (vạn vật hữu linh) or totemism.

This is not the case of the Thaï living in Northern Thailand, Upper Burma, Laos which were occupied at this time by Indianized and Buddhist theravàda Môn-Khmer kingdoms (Angkorian empire, Môn Dvaravati, Haripunchai, Lavo kingdoms etc …) after the dislocation of Indianized Funan kingdom. The Môn had a key rôle in the transmission of Theravadà Buddhism from Sinhalese tradition for Thai newcomers.

- Social and political organization of the Thaï

- Sukhothai kingdom

- Sukhothai Art

- Ayutthaya kingdom

- Pictures of Oriental Venice (Vọng Các)

- Bangkok (Vọng Các)

- Botanical garden Noong Nooch (Pattaya)

(1): Pays des pandas. C’est aussi ici qu’on a découvert la culture de Ba-Shu célèbre pour ses masques zoomorphes de Sanxingdui et pour le mystère des signes sur les armures. C’est aussi le royaume de Shu-Han (Thục Hán) de Liu Bei (Lưu Bị) à l’époque des Trois Royaumes.(Tam Quốc)

(2) Race de l’Asie du Sud-Est préhistorique.

(3): Comment s’est peuplé le Siam, ce qu’est aujourd’hui sa population. Alfred Raquez, (publié en 1903 dans le Bulletin du Comité de l’Asie Française). In: Aséanie 1, 1998. pp. 161-181.

(4) Indochina in wider sense. This is not French Indochina.

(5) The Âu Lạc kingdom of An Dương Vương was annexed by Chinese General Zhao To (Triệu Đà) who later became the founder of Nanyue kingdom. This one will be in turn under the control of Han dynasty, half a century later.

Bibliography