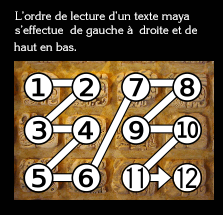

Cho đến năm 1950, nhờ nhà ngôn ngữ nga Yuri Knorosov mà hệ thống chữ viết Maya được giãi mã. Ông nầy đã chứng minh lối viết của người Maya trong việc phiên âm là loại logo âm tiết (từ 900 đến 1200 dấu) so với lối viết của người Ai Cập (734 dấu). Rồi đến 1978, nhà nghiên cứu văn khắc người Mỹ, ông J. Juteson của đại học Stanford đưa vào trong luận án dành về văn tự của người Maya, một ý niệm về việc bổ sung ngữ âm. Có luôn cả văn phạm của người Maya được cung cấp gần đây trong những năm 1980-1990 với các công việc của L. Schele (1982), B. Macleod (1983) và V. Bricker (1986). Nhờ đó mà sự hiểu biết về lối viết của người Maya đuợc thông suốt từ đây. Ngày nay, có thể khẳng định là chữ viết của người Maya là loại logo âm tiết. Nhờ sự tiến triển trong việc giãi mã và các cuộc khai quật mà cái nhìn về người Maya cũng được thay đổi nhất là với những gì họ để lại trong kho tàng tượng hình gồm có hiện nay hơn mười ngàn văn bản. Muốn hiểu một văn tự của người Maya, chúng ta phải đọc từ trái qua phải và từ trên xuống dưới.

Trước đây, chúng ta thường cho rằng người Maya là những người hiền hòa so với người Aztec hiếu chiến. Nhưng nhờ những khám phá khảo cổ gần đây về một số văn bản chữ tượng hình bao gồm các cột (hoặc tấm bia) kỷ niệm, bàn thờ, bản treo tường vân vân… chúng ta mới biết rằng họ cũng rất ưa thích chiến tranh. Đế chế của họ không dựa trên một tổ chức tập trung như của người Inca ở dãy núi Andes. Tuy nhiên, giống như người Hy Lạp, họ sống tập trung ở các thành bang và liên tục chiến đấu với nhau để chiếm quyền bá chủ. Họ đôi khi được gọi là người Hy Lạp của thế giới mới.

Trong mỗi thành phố, có một vị vua thần linh, người nầy được giao nhiệm vụ làm trung gian giữa thần dân và thế giới thần linh, tựa như pháp sư thời xưa. Ngoài việc cung cấp thực phẩm và dùng sức dành được chiến thắng chống lại kẻ thù của mình, nhà vua cần phải bắt tù nhân để hiến tế máu sau đó và mong có được ân huệ của các vị thần linh nhằm đảm bảo sự vĩnh cửu của thành phố của mình trước những thảm họa thiên nhiên (động đất, bão, biến đổi khí hậu vân vân). Người ta cũng thường thấy các chức sắc cao cấp Maya thực hiện nghi lễ trích máu với dao bằng bạch kim hoặc cái gai nhọn của con cá đuối. Mặc dù họ đã phải chịu đựng những hình thức đau đớn trên lưỡi và dương vật của họ, họ vẫn thấy rằng đây là hành động tự nguyện của họ, một sự hy sinh cao cả, vì máu được coi là tài sản quý giá nhất của con người, được dùng để duy trì trật tự vũ trụ và lợi ích của triều đại.

Các lễ vật cúng được thấy rất nhiều và đa dạng. Ngoài máu, họ còn có thể nuôi dưỡng các vị thần bằng mùi và vị. Đôi khi, theo truyền thống của họ, họ quen ném nạn nhân, đặc biệt là các cô gái và trẻ em còn trinh, xuống giếng (hoặc cenote). Đây là trường hợp của Giếng Hy sinh tại Chichen Itza, nơi xương người được tìm thấy (13 sọ của đàn ông, 21 trẻ em và 8 phụ nữ) nhờ quá trình thoát nước được thực hiện bởi các nhà khảo cổ học. Người cai tri (hay lãnh chúa) hay thường tổ chức việc thờ cúng các thần thánh này nên được họ bảo vệ và tôn trọng trong tư tưởng của người Maya. Chính vì thế khi qua đời, lãnh chúa được đi theo con đường gắn liền với sự chuyển động vũ trụ của mặt trời hay mặt trăng để xâm nhập vào âm phủ (thế giới ngầm) và tái sinh ở thiên giới để trở thành một thần thánh nhờ sức mạnh siêu nhiên được ban cho bởi các vị thần. Mặt khác, đối với một người Maya bình thường thì người nầy phải chết trong địa ngục sau một hành trình gian nan đầy nguy hiểm nhưng có thể trở lại trần gian trong một số dịp nhất định với sự đồng ý của thần chết để tham gia vào các nghi lễ do con cháu người nầy thực hiện.

Sự tôn kính mà người Maya bày tỏ với các vị thần của họ thông qua việc hiến tế con người và sự hy sinh bản thân (sẹo và đâm xuyên qua da thịt) đã làm mờ đáng kể cho hình ảnh của họ. Đây là lý do tại sao khi đến lãnh thổ của họ, người Tây Ban Nha xem coi họ là người man rợ tại vì những phong tục nhất định nầy. Tuy nhiên, họ đã phát minh ra con số 0 hai thế kỷ trước khi người châu Âu mượn nó từ người Ả Rập sau các cuộc Thập tự chinh. Số 0 này thường được biểu thị bằng một cái vỏ, một bông hoa và đôi khi là một hình xoắn ốc. Họ quan tâm đến toán học và thiên văn học. Họ biết cách sử dụng riêng các số dương.

Dân tộc Maya là một trong số ít các dân tộc bị thu hút bởi thời gian. Nhờ biết sử dụng hệ thống vigesimal (dựa trên hệ nhị thập phân), họ đã thiết lập nhiều lịch để dự đoán các sự kiện quan trọng (ví dụ như các lời tiên tri), xác định các ngày quan trọng trong lịch sử và chuẩn bị thời gian thuận lợi cho các nghi lễ để các lực siêu nhiên mang lại tích cực cho nông nghiệp và cuộc sống hàng ngày của họ bằng cách trở lại các mùa màng và thời kỳ màu mỡ của trái đất. Lịch của họ cũng chính xác như lịch của chúng ta. Họ đã có thể tính toán được các giai đoạn của sao Kim và thời gian đồng hành của sao Hỏa với độ chính xác đáng kinh ngạc 780 ngày mặc dù chúng ta biết rằng vào thời điểm đó, họ hoàn toàn không có các thiết bị quang học. Người ta có thể nghĩ rằng ngoài khả năng quan sát và kiên nhẫn của họ, họ còn có khả năng suy luận và kết luận rất xuất sắc. Đây là trường hợp của một trong những đài quan sát của người Maya ở Chichén Itzá, Yucatan, Caracol (hay con ốc sên trong tiếng Tây Ban Nha), nơi người ta có thể theo dõi nơi chân trời các vị trí khác nhau của các thiên thể (mặt trời, mặt trăng hoặc sao Kim) từ cửa sổ của tháp. Sự di chuyển của các thiên thể vẫn là một lĩnh vực đặc biệt đối với người Maya vì nó có liên quan chặt chẽ đến việc thờ phượng các vị thần linh. Những vị thần này có mặt ở khắp mọi nơi, ngay cả trong thế giới bên dưới, nơi có nhiều vị thần linh và nhiều cấp độ (9 vị thần, 9 tầng dưới đất).

Malgré cela, une percée significative dans le déchiffrement de l’écriture maya eut lieu dans les années 1950 grâce aux travaux du linguiste russe Yuri Knorosov. Ce dernier parvint à prouver que l’écriture utilisée par les Mayas pour la transcription de leur langue, était de type logo-syllabique (de 900 à 1200 signes) comparable à l’égyptien classique (734 signes). Puis en 1978, l’épigraphiste américain de l’université Stanford, J. Justeson introduisit dans sa thèse consacrée à l’écriture maya, l’idée de compléments phonétiques. Même une grammaire se constitua récemment dans les années 1980-1990 avec les travaux de L. Schele (1982), B. Macleod (1983) et V. Bricker (1986). Cela facilite la meilleure compréhension de la tradition écrite par des Mayas.

Aujourd’hui, on peut dire que l’écriture maya est de type logo-phonétique. Grâce à cette avancée dans le décryptage et dans les fouilles archéologiques, on est obligé de modifier la vision qu’on a eue à l’égard des Mayas en saisissant tout ce qu’ils avaient laissé dans le corpus hiéroglyphique composé actuellement de plus de dix mille textes. Pour connaître le contenu d’un texte maya, il faut suivre l’ordre de lecture qui s’effectue de gauche à droite et de haut en bas.

Dans le passé, on avait l’habitude de présenter les Mayas comme pacifiques, comparés à des Aztèques belliqueux et guerriers. Mais grâce aux découvertes archéologiques récentes de plusieurs textes hiéroglyphiques couvrant les colonnes commémoratives (ou stèles), les autels, les panneaux muraux etc…, on sait qu’ils étaient aussi adeptes de la guerre.

Leur empire ne s’appuyait pas sur une organisation centralisée comme les Incas des Andes. Par contre, analogues aux Grecs, ils vivaient regroupés dans les cités-états et ils ne cessaient pas de guerroyer entre eux en quête d’hégémonie. On les appelle parfois sous le nom des Grecs du nouveau monde.

Dans chaque cité, il y a un roi d’essence divine, chargé d’être le médiateur entre ses sujets et le monde des dieux comme le chaman de jadis. Outre la procuration de la nourriture et la force de travail gratuite en cas des victoires contre ses ennemis, le monarque a besoin de faire des prisonniers destinés aux sacrifices de sang dans le but de s’attirer les grâces des dieux et d’assurer l’éternité de sa cité face aux calamités naturelles (séismes, ouragans, changements climatiques etc…). Il est fréquent de voir aussi l’acte rituel de la saignée effectuée par les hauts dignitaires mayas à l’aide d’un couteau en obsidienne ou d’un aiguillon de pastenague. Malgré les mortifications très douloureuses soit sur leur langue soit leur pénis, ces derniers trouvaient dans leur acte volontaire une sacrifice suprême car le sang qui était considéré comme le bien le plus précieux de l’homme, servait à maintenir l’ordre cosmique et les intérêts dynastiques.

Les offrandes étaient multiples et diverses. Outre le sang, ils pouvaient nourrir les dieux avec des odeurs et des saveurs. Parfois, dans leur tradition, ils étaient habitués à jeter dans le puits (ou cénote) des victimes, en particulier des jeunes filles vierges et des enfants. C’est le cas de la Cenote du Sacrifice à Chichen Itza où on a retrouvé des ossements humains ( 13 crânes d’hommes, 21 d’enfants et 8 de femmes) lors du drainage effectué par des archéologues. Le souverain qui célébrait ainsi ce culte divin était traité avec respect et protégé par les divinités dans la pensée maya. C’est pourquoi lors de sa mort, il emprunta le même chemin lié au mouvement cosmique du soleil ou de la lune pour pénétrer dans l’inframonde (milieu souterrain) et renaquit dans le monde céleste pour devenir une divinité grâce au pouvoir surnaturel accordé par les dieux.

Par contre, pour un Maya ordinaire, il devait mourir au fond de l’inframonde après un long parcours périlleux mais il pouvait revenir sur terre en certaines occasions avec le consentement des dieux de la mort pour participer aux rites pratiqués par ses descendants. L’hommage que les Mayas avaient accordé à leurs dieux par les sacrifices humains et les autosacrifices (scarification et percement des chairs) porte un préjudice considérable à leurs images. C’est pourquoi, lors de l’arrivée des Espagnols sur leur territoire, ils étaient considérés comme des barbares à cause de certaines coutumes. Pourtant ils ont inventé le zéro deux siècles avant l’emprunt des Européens aux Arabes après les croisades. Ce chiffre 0 était représenté souvent par une coquille, une fleur et parfois une spirale. Ils étaient férus de mathématiques et d’astronomie. Ils savaient utiliser exclusivement des nombres positifs.

Les Mayas étaient l’un des rares peuples qui ont été fascinés par le temps. Grâce à leur système vigésimal (à base 20), ils établissaient plusieurs calendriers permettant de prédire d’importants évènements (les prophéties par exemple), de fixer les grandes dates de l’histoire et de préparer les moments propices aux cérémonies destinées à influencer positivement l’effort des forces surnaturelles sur leur agriculture et leur vie quotidienne par le retour des saisons et les époques de fertilité de la terre. Leur calendrier solaire était aussi précis que le nôtre. Ils ont réussi à calculer les phases de Vénus et la période synodique de Mars de 780 jours avec une précision stupéfiante bien qu’on sache qu’à cette époque, ils furent dépourvus entièrement des instruments d’optique.

On est amené à penser qu’outre leur faculté d’observation et leur patience inouïe, ils avaient un sens de la logique et une déduction extrêmement remarquable. C’est le cas de l’un des observatoires mayas trouvés dans le Yucatan à Chichén Itzá, le Caracol (ou l’escargot en espagnol) où on peut suivre à l’horizon différentes positions des astres (soleil, lune ou Vénus) depuis les lucarnes de la tour. Le mouvement de ceux-ci restait un domaine privilégié pour les Mayas car il était lié étroitement au culte des dieux. Ces derniers foisonnaient partout même dans l’inframonde où il y avait autant de dieux que de niveaux. (9 dieux, 9 niveaux souterrains).

Despite this, a significant breakthrough in deciphering Maya writing occurred in the 1950s thanks to the work of the Russian linguist Yuri Knorosov. He managed to prove that the writing used by the Mayas for transcribing their language was of a logo-syllabic type (ranging from 900 to 1200 signs), comparable to classical Egyptian (734 signs). Then, in 1978, the American epigraphist from Stanford University, J. Justeson, introduced the idea of phonetic complements in his thesis dedicated to Maya writing. Even a grammar was developed recently in the 1980s-1990s with the work of L. Schele (1982), B. Macleod (1983), and V. Bricker (1986). This facilitates a better understanding of the written tradition by the Mayas.

Today, it can be said that Maya writing is of the logo-phonetic type. Thanks to this progress in decipherment and archaeological excavations, we are forced to change the view we had of the Mayas by understanding everything they left in the hieroglyphic corpus currently composed of more than ten thousand texts. To know the content of a Maya text, one must follow the reading order which is done from left to right and from top to bottom.

In the past, the Mayas were usually presented as peaceful, compared to the warlike and warrior Aztecs. But thanks to recent archaeological discoveries of several hieroglyphic texts covering commemorative columns (or stelae), altars, mural panels, etc., we know that they were also keen on war.

Their empire was not based on a centralized organization like the Incas of the Andes. However, similar to the Greeks, they lived grouped in city-states and continuously waged war among themselves in search of hegemony. They are sometimes called the Greeks of the New World.

In each city, there is a king of divine essence, responsible for being the mediator between his subjects and the world of the gods, like the shaman of old. Besides providing food and free labor in case of victories against his enemies, the monarch needs to take prisoners destined for blood sacrifices to gain the favor of the gods and ensure the eternity of his city in the face of natural calamities (earthquakes, hurricanes, climate changes, etc.). It is also common to see the ritual act of bloodletting performed by high Maya dignitaries using an obsidian knife or a stingray spine. Despite the very painful mortifications on their tongue or penis, they found in their voluntary act a supreme sacrifice because the blood, considered the most precious asset of man, served to maintain cosmic order and dynastic interests.

The offerings were many and varied. In addition to blood, they could feed the gods with smells and flavors. Sometimes, in their tradition, they were accustomed to throwing victims into the well (or cenote), especially virgin girls and children. This is the case of the Cenote of Sacrifice in Chichen Itza where human bones (13 skulls of men, 21 of children and 8 of women) were found during the drainage carried out by archaeologists. The sovereign who celebrated this divine cult in this way was treated with respect and protected by the deities in Mayan thought. Therefore, upon his death, he took the same path linked to the cosmic movement of the sun or the moon to enter the underworld (underground environment) and was reborn in the celestial world to become a divinity thanks to the supernatural power granted by the gods.

On the other hand, for an ordinary Maya, he had to die at the bottom of the underworld after a long perilous journey but he could return to earth on certain occasions with the consent of the gods of death to participate in the rites practiced by his descendants. The homage that the Maya had paid to their gods through human sacrifices and self-sacrifices (scarification and piercing of the flesh) caused considerable harm to their image. This is why, when the Spanish arrived on their territory, they were considered barbarians because of certain customs. Yet they invented zero two centuries before the Europeans borrowed it from the Arabs after the Crusades. This number 0 was often represented by a shell, a flower and sometimes a spiral. They were keen on mathematics and astronomy. They knew how to use only positive numbers.

The Maya were one of the few peoples fascinated by time. Using their vigesimal (base 20) system, they established several calendars that allowed them to predict important events (prophecies, for example), to fix the major dates in history, and to prepare the right moments for ceremonies designed to positively influence the efforts of supernatural forces on their agriculture and daily life through the return of the seasons and the periods of fertility of the earth. Their solar calendar was as precise as ours. They managed to calculate the phases of Venus and the synodic period of Mars of 780 days with astonishing precision, although it is known that at this time they were entirely deprived of optical instruments.

We are led to believe that in addition to their powers of observation and their incredible patience, they had a sense of logic and an extremely remarkable deduction. This is the case of one of the Mayan observatories found in the Yucatan at Chichén Itzá, the Caracol (or the snail in Spanish) where one can follow on the horizon different positions of the stars (sun, moon or Venus) from the skylights of the tower. The movement of these remained a privileged domain for the Mayans because it was closely linked to the worship of the gods. The latter abounded everywhere even in the underworld where there were as many gods as there were levels. (9 gods, 9 underground levels).