French version

Being known in China under the name « Yi », the Lô Lô are also called Mùn Di, Màn Di, La La, Qua La, Ô Man, Lu Lộc Mà by the Vietnamese. They belong to the Tibeto-Burman ethno-linguistic group. A large number live in the highland areas of China (Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou et Kouang Si) except a little minority native of Yunnan installed in the Upper Tonkin at the time of migratory flows which were appeared in the 15th and 18 th centuries. At present, the population of this ethnic group amounts to about 4000 individuals in Vietnam. According to ethnologists, the Lô Lô are descendants of the nomadic people and sheep farmer Qiang (Khương tộc ) who emigrated from the South East of Tibet for taking up permanent residence in Sichuan (Tứ Xuyên) and Yunnan (Vân Nam).

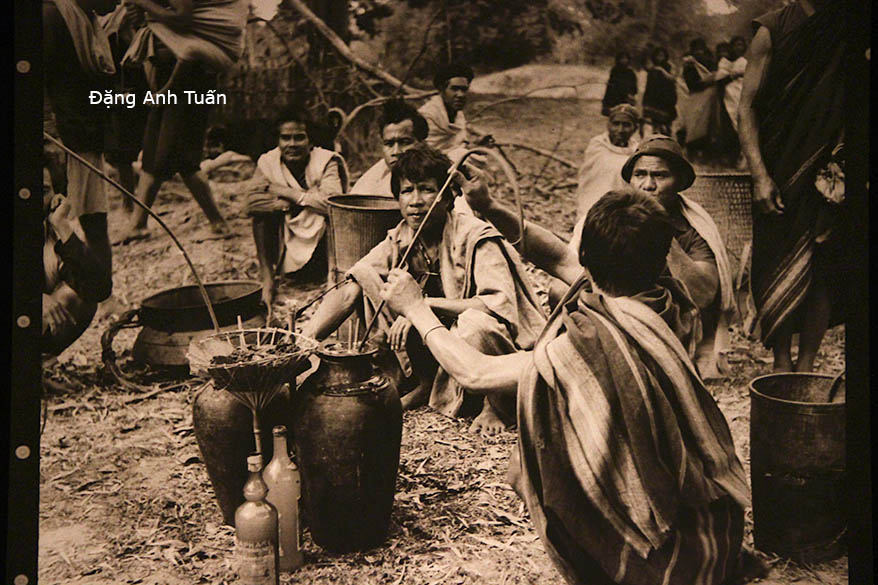

© Đặng Anh Tuấn

The one of 54 ethnic minorities in Vietnam

At the period of Chunqiu (or Spring and Autumn period)(Xuân Thu in Vietnamese), this people was always at war with the inhabitants of Yellow River (Hoàng Hạ), ancestors of the Chinese. Their expansion was stopped by the duke Mu of the Qin state (Tần Mục Công) which ruled between -660 et -621 and was one of five famous hegemons (Bá chủ) at this time thanks to the contribution made by his talented chancellor Baixi Li ( Bá Lý Hệ).

In the ethnic group Lô Lô, there are two small groups: the coloured Lô Lô (Lô Lô hoa ) and the black Lô Lô (Lô Lô đen). They live by using traditional irrigated rice method and slashand-burn agriculture with most important plants as corn, sticky rice and ordinary rice. That is what we see in Đồng Văn et Mèo Vạc districts on the fields and milpas. By contrast, in the Bảo Lạc district, except the permanents milpas, they use the field terraces. Their main food is the maize flour immersed in boiling water. The broth is not missing in their meal, which always requires the use of bowls and spoons in wood.

彝族 (Dân tộc Lô Lô)

In general, their homes are conveniently located in high and dry areas overlooking the valleys. They prefer to live near dense forests because forests and streams are considered by them as living spaces of the soil genius. They are just people who like to live in harmony with nature. They use the hoods with two shoulder straps in rattan or a variety of bamboo (giang) for transporting their possessions. They prefer to be married with people of their sample ethnic. They also practice exogamy just in case the marriage takes place between people from different parentages. The Lô Lô are monogamous. The young bride lives in the family of his husband. The adultery is condemned in their traditions. However, the levirate marriage is tolerated because the little brother of the deceased can take for the spouse his sister-in-law. Similarly, the son of the parternal aunt is allowed to be married with the daughter of the maternal uncle (cô cậu) but it is strictly forbidden to do the opposite.

In the family, everything is decided by the husband. The daughters inherit jewelry of their mother and receive upon their marriage a dowry. About the heritage itself, the beneficiaries are male children in the family. When a person is died, his family organises a ritual ceremony in the intention of helping his soul to find the path towards his ancestors. Being known under the name » dance of the spirits », this rhythmic manifestation is led by his son-in-law carrying on his shoulders a bag containing a cloth ball representing the head of the deceased. Sometimes, instead of this ball, we find a piece of wood or a squash on which is drawn the figure of the deceased. This shows that the traces of the practice of headhunting remain vivacious among the Lô Lô. During the funeral, this son-in-law must carry one of the extremities of the coffin. It is him and brothers of the widow to throw the first handfuls of earth in the tomb of the deceased.

The Lô Lô clearly distinguish between close ancestors (in less than 5 generations) and distant ancestors (beyond six generations). For close ancestors, there is always an own altar in each family while for distant ancestors, the ritual takes place in the home of the lineage head (trưởng tộc). Like the Vietnamese people, the Lô Lô have the bronze drums which are used only during the funeral. These drums are always in pairs: a male and a female. They are placed in the supports next to feet of the deceased so that their eardrums are opposing each other. Then a player stands between them and strikes them alternatively with a unique drum stick. A beat for the male drum followed by another beat for the female drum, all of this is in a regular cadence.

The player must be single or a married man whose the wife is not pregnant at the funerals. Being a sacred instrument, the drum is buried or hidden in a place which is simultaneously clean and discreet. There is only the familial lineage head who knows this emplacement.

For the Lô Lô, there is a legend concerning the bronze drum:

Once upon a time, the country and its inhabitants were swallowed by the flood. Having had compassion for young girls who were dying, God provided assistance to them by putting respectively the big sister in the great bronze drum and the younger in the small drum. The drums were not drowned by the flood, which saved two young girls. After the deluge, they taked refuge in the mountains and were married. They had thus become the ancestors of ressurected humans.

Like the Vietnamese and the Chinese, the Lô Lô celebrate their new year at which are added other rites and festivals. The is the case of the ritual of new rice, the celebration of the 5th day of the 5th moon, that of the 15th day of the 7th moon etc.. We don’t forget to mention also the dance under the moonlight . The latter may last all night and assembles either a majority of girls and boys or a group of young girls or married womens. The dance starts with the formation of the circle carried out by the dancers who place their hands on the shoulders of others. They are accompanied by songs and movements simulating the daily activities such as the rice pounding and winnowing, the fruit picking or the embroidery etc …

Being the favourite entertainment for youth, the dance under the moonlight takes place on the site near to the village and it can take up to the morning light.

Althought the Lô Lô are not numerous in Vietnam, they are distinguished from other ethnies by their flamboyant clothing and the deep attachment to nature.

Althought the Lô Lô are not numerous in Vietnam, they are distinguished from other ethnies by their flamboyant clothing and the deep attachment to nature.

Bibliographic references:

- Ethnic minorities in Vietnam. Đặng Nghiêm Vạn, Chu Thái Sơn, Lưu Hùng . Thế Giới Publishers Hànội 2010

- Mosaïque culturelle des ethnies du Vietnam. Nguyễn Văn Huy. Maison d’édition de l’éducation. 1997

- Notes sur quelques danses de minorités ethniques du Nord Vietnam. Phạm Thị Điền. Etudes vietnamiennes. Tome 39 n°3