Version française

Version anglaise

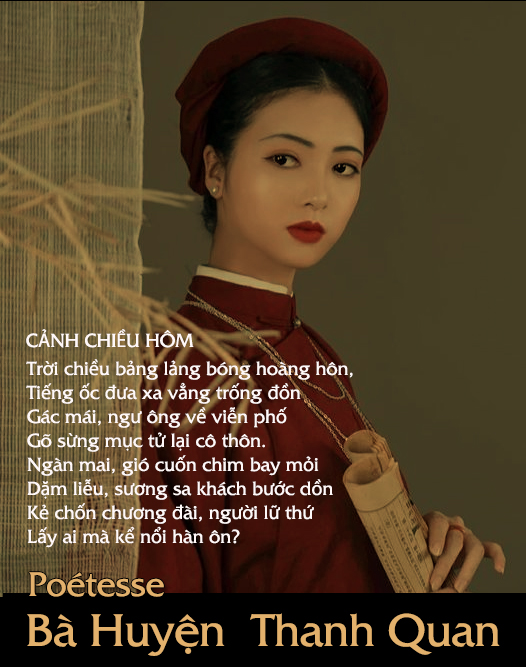

Ít ai biết tên thật của bà trong làng văn học Việt Nam ở đầu thế kỷ XIX. Chỉ gọi bà là bà huyện Thanh Quan vì chồng bà tên là Lưu Nghị, có đậu cử nhân năm 1821 (Minh Mạng thứ 2) và có một thời làm tri huyện Thanh Quan (tỉnh Thái Bình). Thật sự tên thật của bà là Nguyễn Thị Hinh người phường Nghi Tâm, huyện Vĩnh Thuận, gần Hồ Tây, quận Tây Hồ (Hà Nội). Cha của bà là ông Nguyễn Lý (1755-1837) đỗ thủ khoa năm 1783 dưới đời vua Lê Hiến Tông. Qua các bài thơ nôm bi thương của bà, chúng ta thường thấy có sự nhớ thương day dứt không nguôi, có một nỗi buồn của nữ sĩ đa tài về những sự thay đổi của cảnh vật thâm trầm nhất là Thăng Long nơi mà sinh ra cũng không còn là kinh đô của đất nước mà là Huế. Còn chồng bà cũng bị cách chức một thời sau đó được thăng lên chức Bát phẩm Thư lại bộ Hình và mất sớm ở tuổi 43. Bà rất nỗi tiếng « hay chữ » nhất là về loại thơ Đường. Loại thơ nầy còn được gọi là cổ thi vì được dùng cho việc thi cử tuyển chọn nhân tài, rất phổ biến ở Việt Nam vào thời Bắc thuộc (Nhà Đường). Bởi vậy thơ nầy mới có tên là thơ Đường.

Lọai thơ nầy chỉ vỏn vẹn có 8 câu ; mỗi câu 7 chữ tức là có tất cả là 8×7= 56 chữ thế mà bà mô tả và dựng lên được một cách tài tình, một bức tranh tuyệt vời từ ngọai cảnh lẫn nội dung. Tuy nhiên thể thơ nầy nó có luật rất chặt chẽ và được điều chỉnh bởi ba quy tắc thiết yếu :vần, điệu và đối khiến ở Việt Nam từ 1925 thì các thi sĩ không còn tôn trọng quy luật bằng-trắc để có thể hiện được sự lãng mạn của mình trong từng câu thơ. Nhưng những bài thơ thất ngôn bát cú của bà Thanh Quan thì phải xem đây là những viên ngọc quý trong làng văn học Việt Nam. Bà đã thành công trong việc vẽ được một cảnh quan nhỏ bé với 56 chữ và bày tỏ cảm xúc sâu sắc của mình một cách tinh tế và sử dụng ngôn ngữ Hán Việt trong thể thơ thất ngôn bát cú một cách điêu luyện.Theo nhà nghiên cứu Trần Cửu Chấn, thành viên của Viện hàn lâm văn học và nghệ thuật Paris thì các bài thơ của bà được xem như là những viên ngọc quý được bà chọn lọc và gọt dũa đặt trên vương miện hay được cắt bằng men.

Các bài thơ Đường của bà không chỉ mang tính chất cổ điển mà còn thể hiện được sự điêu luyện trong cách dùng chữ. Bà còn có tài năng biết biến thành những biểu tượng vô hồn như đá (Đá vẫn trơ gan cùng tuế nguyệt), nước (Nước còn chau mặt với tang thương), hay cỏ cây (Cỏ cây chen đá, lá chen hoa) thành những vật thể sinh động, còn mang tính và hồn người và còn biết dùng màu sắc đậm nhạt để thể hiện sự tương phản (Chiều trời bảng lảng bóng hoàng hôn/ Vàng tỏa non tây bóng ác tà) hay đưa quá khứ về cùng với hiện tại (Lối xưa xe ngựa hồn thu thảo/Nền cũ lâu đài bóng tịch dương/Ngàn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ) khiến các bài thơ tả cảnh của bà trở thành những bức tranh thiên nhiên tuyệt vời cũng như các bức tranh thủy mà họa sĩ dùng bút lông vẽ trên lụa với sắc thái đậm nhạt nhờ quan sát chính xác.

Những bài thơ Đường của bà rất được các nho gia xưa ngâm nga yêu chuộng. Tuy rằng chỉ tả cảnh và bày tỏ nỗi cảm xúc của mình nhưng lời thơ rất thanh tao của một bà thuộc tầng lớp qúy tộc cao có học thức thường nghĩ ngợi đến nhà, đến nước. Đây là lời nhận xét của nhà nghiên cứu văn học Dương Quảng Hàm. Bà có tấm lòng thương tiếc nhà Lê nhưng đồng thời chỉ bày tỏ tâm sự của một người không bằng lòng với thời cục, mong mỏi sự tốt đẹp như đã có ở một thời xa xôi trước đây mà thôi. (Nghìn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ/ Cảnh đấy người đây luống đoạn trường). Cụ thể bà còn giữ chức Cung Trung Giáo Tập để dạy học cho các công chúa và cung phi dưới thời vua Minh Mang cûa nhà Nguyễn. Có một lần vua Minh Mạng có một bộ chén kiểu của Trung Quốc mới đưa sang và vẽ sơn thủy Việt Nam cũng như một số đồ sứ kiểu thời đó. Vua mới khoe và ban phép cho bà được làm một bài thơ nôm. Bà liền làm ngay hai câu thơ như sau :

Như in thảo mộc trời Nam lại

Đem cả sơn hà đất Bắc sang.

khiến làm vua rất hài lòng và thích thú. Phài nói người Trung Hoa hay thường xem trọng sơn hà nên thường thấy ở trên các đồ kiểu còn ở Việt nam ta thì rất hướng về ruộng lúa xanh tươi thế mà bà biết vận dụng thành thạo chữ nôm để có hai câu thơ đối gợi ý tuyệt vời.

Nhưng sau khi chồng bà qua đời, một tháng sau bà xin về hưu và trở về sinh sống ở quê quán của mình cùng 4 đứa con. Bà mất đi ở tuổi 43 vào năm 1848.(1805-1848)

Các bài thơ nôm của bà tuy không nhiều chỉ có 6 bài nhưng thể hiện được tinh thần thanh cao của các nho sĩ, cùng với tinh túy của Đường thi. Viết chữ Hán thì đã khó mà sang chữ Nôm thì càng khó hơn vì khó học mà còn dùng lời văn trang nhã, điêu luyện và ngắn gọn như bà để giữ được quy tắc chặt chẽ của thơ Đường. Thật không có ai có thể bằng bà đựợc nhất là bà biết dùng ngoại cảnh để bày tỏ nỗi cô đơn và tâm trạng của mình. Bà cũng không biết cùng ai để chia sẻ cái ray rứt ở trong lòng (Một mảnh tình riêng ta với ta./Lấy ai mà kể nổi hàn ôn?). Bà luôn luôn tiếc nuối xót xa về quá khứ với một tâm hồn thanh cao lúc nào cũng hướng về gia đình và quê hương.

QUA ĐÈO NGANG

Bước tới đèo Ngang, bóng xế tà

Cỏ cây chen lá, đá chen hoa

Lom khom dưới núí, tiều vài chú

Lác đác bên sông, chợ mâý nhà

Nhớ nước đau lòng, con quốc quốc

Thương nhà, mỏi miệng cái gia gia

Dừng chân đứng lại: trời non nước

Một mảnh tình riêng ta với ta.

THĂNG LONG HOÀI CỔ

Tạo hoá gây chi cuộc hí trường

Đến nay thắm thoát mấy tinh sương

Lối xưa xe ngựa hồn thu thảo

Nền cũ lâu đài bóng tịch dương.

Đá vẫn trơ gan cùng tuế nguyệt

Nước còn cau mặt với tang thương

Nghìn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ

Cảnh đấy, người đây luống đoạn trường.

CẢNH CHIỀU HÔM

Trời chiều bảng lảng bóng hoàng hôn,

Tiếng ốc đưa xa vẳng trống đồn

Gác mái, ngư ông về viễn phố

Gõ sừng mục tử lại cô thôn.

Ngàn mai, gió cuốn chim bay mỏi

Dặm liễu, sương sa khách bước dồn

Kẻ chốn chương đài, người lữ thứ

Lấy ai mà kể nổi hàn ôn?

CHIỀU HÔM NHỚ NHÀ

Vàng tỏa non tây bóng ác tà

Đầm đầm ngọn cỏ tuyết phun hoa

Ngàn mai lác đác chim về tổ

Dậm liễu bâng khuâng khách nhớ nhà

Còi mục gác trăng miền khoáng dã

Chài ngư tung gió bãi bình sa

Lòng quê một bước dường ngao ngán

Mấy kẻ chung tình có thấu là..?

CHÙA TRẤN BẮC

Trấn bắc hành cung cỏ dãi dầu

Ai đi qua đó chạnh niềm đau

Mấy tòa sen rớt mùi hương ngự

Năm thức mây phong nếp áo chầu

Sóng lớp phế hưng coi đã rộn

Chuông hồi kim cổ lắng càng mau

Người xưa cảnh cũ nào đâu tá

Ngơ ngẩn lòng thu khách bạc đầu

CẢNH THU

Thấp thoáng non tiên lác đác mưa

Khen ai khéo vẽ cảnh tiêu sơ

Xanh um cổ thụ tròn xoe tán,

Trắng xoá tràng giang phẳng lặng tờ.

Bầu dốc giang sơn, say chấp rượu,

Túi lưng phong nguyệt, nặng vì thơ

Cho hay cảnh cũng ưa người nhỉ ?

Thấy cảnh ai mà chẳng ngẩn ngơ ?…

Peu de gens connaissaient son vrai nom dans la communauté littéraire vietnamienne au début du XIXème siècle. On l’appelait simplement Madame le sous-préfet du district Thanh Quan parce que son mari Lưu Nghi fut reçu aux trois concours de la licence en 1821 sous le règne de l’empereur Minh Mang et fut un temps sous-préfet du district de Thanh Quan (province de Thái Binh). En fait, son vrai nom était Nguyễn Thị Hinh. Elle était issue du village Nghi Tâm du district de Vĩnh Thuận, près du lac de l’Ouest dans l’arrondissement de Tây Hồ (Hanoï). Son père était Mr Nguyễn Lý (1755-1837) ayant eu réussi être le premier dans le concours interprovincial en 1783 sous le règne du roi Lê Hiến Tông. À travers à ses poèmes élégiaques, nous remarquons toujours la douleur et la tristesse sempiternelle de la poétesse talentueuse face aux changements ayant un profond impact au paysage, en particulier à l’ancienne capitale Thăng Long où elle est née. Cette dernière n’était plus la capitale du pays mais c’était plutôt Huế. Son mari fut licencié durant un certain temps avant d’être promu au poste de secrétaire du Ministère de la Justice. Il fut décédé prématurément à l’âge de 43 ans. Elle a un penchant pour la versification Tang. Ce type de poésie est également appelé la poésie antique car il est utilisé dans les concours destinés à recruter des gens de talent et il est très populaire au Vietnam durant la période de domination des gens du Nord (dynastie des Tang). C’est pourquoi il s’appelle la poésie des Tang.

Ce type de poème composé seulement de 8 vers de 7 pieds permet d’avoir un total de 8 × 7 = 56 mots. Pourtant la poétesse réussit à décrire avec ingéniosité un magnifique tableau porté à la fois sur le paysage externe et le contenu. Cependant, ce poème des Tang a des règles très strictes et est régie par trois principes essentiels: la rime, le rythme et le parallélisme. Depuis 1925 au Vietnam, les poètes ne respectent plus les règles de la métrique pour s’exprimer librement dans le but d’obtenir le lyrisme dans chaque vers. Mais les poèmes des Tang de Mme Thanh Quan doivent être considérés comme un joyau précieux dans le monde littéraire vietnamien. Elle a réussi à décrire et à brosser un petit paysage avec 56 mots et a exprimé ses profonds sentiments de manière raffinée. Elle a utilisé la langue sino-vietnamienne sous une forme poétique de 8 vers de 7 pieds avec adresse. Selon le chercheur Trần Cửu Chấn, membre de à l’Académie des Lettres et des Arts de Paris, ses poèmes Tang sont considérés comme des perles précieuses qu’elle sélectionne, polit et met sur une couronne en or ou ciselée en émail.

Ses poèmes n’ont pas seulement le caractère classique mais ils traduisent aussi la virtuosité dans l’utilisation des mots. Elle a également le talent de savoir transformer des éléments sans vie tels que la pierre (la pierre reste toujours impassible au fil du temps), l’eau (l’eau se montre indignée devant l’instabilité des choses de la vie) ou l’herbe et les arbres (l’herbe et les arbres s’intercalent avec les rochers tandis que les feuilles s’introduisent au sein des fleurs) en des êtres vivants ayant la nature humaine et l’âme et utiliser des couleurs foncée et claire pour faire sortir les contrastes (Sous le ciel blafard, le soir ramène les ombres du crépuscule / Le jaune brille sur les montagnes de l’ouest sous les rayons du soleil couchant) ou rapprocher le passé du présent (Lối xưa xe ngựa hồn thu thảo/ Sur la vieille voie prise par les calèches, se promène l’âme des herbes d’automne)(Nền cũ lâu đài bóng tịch dương/ Les vestiges du palais somptueux sont éclairés par les rayons du soleil couchant) (Ngàn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ/ Au fil des siècles, dans ce miroir antique, on met en parallèle le passé et le présent). Cela fait de ses poèmes Tang décrivant des scènes de paysage en de merveilleuses peintures naturelles comme les aquarelles que l’artiste réussit à peindre au pinceau sur le tissu en soie avec des nuances entre le foncé et clair à l’aide d’une observation rigoureuse.

Ses poèmes des Tang sont très appréciés par les anciens érudits confucéens. Bien qu’ils ne fassent que décrire le paysage et exprimer ses sentiments, les termes employés sont tellement raffinés et écrits par une dame aristocratique très instruite qui pense souvent à son foyer et à son pays. C’est le commentaire du chercheur littéraire Dương Quảng Hàm. Elle avait un attachement profond à la dynastie des Lê mais en même temps elle n’exprimait que les sentiments de quelqu’un qui n’était pas satisfait de la situation actuelle et qui espérait de retrouver ce qui existait auparavant. ( Ngàn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ/Cảnh đấy người đây luống đoạn trường) (Devant ce tableau, mes entrailles se sentent déchirées en morceaux). La preuve est qu’elle acceptait la tâche d’enseigner les princesses et les concubines sous le règne de l’empereur Minh Mạng de la dynastie des Nguyễn. Une fois, ce dernier reçut un nouvel service à thé en céramique venant de la Chine et ayant pour décor le paysage du Vietnam. Il le montra à ses subordonnés et demanda à la poétesse de composer un distique. Elle ne tarda pas à improviser les deux sentences suivantes:

Như in thảo mộc trời Nam lại

Đem cả sơn hà đất Bắc sang.

L’herbe et les arbres du Sud sont reproduits visiblement sur la céramique ainsi que les monts et fleuves du Nord ainsi ramenés.

Sa spontanéité rendit satisfait l’empereur. Il faut reconnaitre que les Chinois font souvent attention aux montagnes et aux fleuves qu’on retrouve souvent sur les objets de décoration. Par contre au Vietnam, on s’attache à la luxuriance des rizières. Elle réussit à saisir l’essentiel et à composer ces deux vers parallèles tout en sachant respecter strictement les règles de poésie des Tang. Lors du décès de son mari, un mois plus tard, elle demanda au roi de lui permettre de désister sa fonction et retourner à sa terre natale avec ses quatre enfants. Elle mourut en l’an 1848 lorsqu’elle n’avait que 43 ans. (1805-1848)

Étant en nombre limité (6 en tout), ses poèmes réussissent à refléter l’esprit noble des poètes et la quintessence de la poésie des Tang. La composition de ces poèmes est déjà difficile en caractères chinois mais elle parait insurmontable en caractères démotiques dans la mesure où il faut respecter en plus les règles strictes de la poésie des Tang. Peu de gens arrivent à l’égaler car elle sait utiliser des mots avec une rare finesse de langage pour révéler sa solitude et son état d’âme tout en s’appuyant sur le pittoresque des scènes de la nature. Elle ne sait non plus à qui elle peut révéler ses confidences. (Một mảnh tình riêng ta với ta./Lấy ai mà kể nổi hàn ôn?). Sous le poids de son état d’âme, elle se sent seule avec soi-même. Elle continue à éprouver des regrets et se retourner vers le passé avec son esprit noble et à penser sans cesse à son foyer et à sa terre natale.

LE COL DE LA PORTE D’ANNAM (*)

Au moment je gravis le Col de la Porte d’Annam, les ombres du crépuscule s’allongent vers l’occident

L’herbe et les arbres s’introduisent dans les rochers, les fleurs éclosent au milieu des feuilles.

Au pied de la montagne marchent quelques bûcherons , le dos courbé sous le faix;

Sur l’autre côté de la rivière s’élève un marché formé de quelques cases éparses.

En pensant avec douleur à la patrie absente le râle d’eau gémit sans arrêts,

Oppressée par l’attachement au foyer, la perdrix pusse des cris ininterrompus.

Je m’arrête sur le chemin et ne vois autour de moi que ciel, montagnes et mer;

Sous le poids de cet état d’âme, je me sens seule avec moi-même.

CRÉPUSCULE (*)

Sous un ciel blafard, le soir ramène les ombres du crépuscule

Au loin le son de la trompe des veilleurs répond au tam-tam du poste de garde.

Déposant sa rame, le vieux pêcheur regagne sa station lointaine;

Le jeune bouvier frappant sur les cornes de son buffle, retourne au hameau solitaire.

Les oiseaux volent avec effort vers les immenses touffes d’abricotiers qui ondulent sous le vent;

Le voyageur presse le pas sur la route que bordent les saules enveloppés de brume.

Moi je reste au logis ; vous , vous êtes en voyage;

À qui pourrais-je exprimer toutes mes confidences?

(*) Extrait du livre intitulé « Les grandes poétesses du Vietnam« , Auteur Trần Cửu Chấn. éditions Thế Giới

Few people knew her real name in the Vietnamese literary community at the beginning of the 19th century. She was simply called Madame the sub-prefect of Thanh Quan district because her husband Lưu Nghi passed the three licensing exams in 1821 under the reign of Emperor Minh Mang and was at one time the sub-prefect of Thanh Quan district (Thái Binh province). In fact, her real name was Nguyễn Thị Hinh. She came from Nghi Tâm village in Vĩnh Thuận district, near West Lake in Tây Hồ ward (Hanoi). Her father was Mr. Nguyễn Lý (1755-1837), who succeeded in being first in the interprovincial exam in 1783 under the reign of King Lê Hiến Tông. Through her elegiac poems, we always notice the eternal pain and sadness of the talented poetess in the face of changes that had a profound impact on the landscape, especially the ancient capital Thăng Long where she was born. The latter was no longer the country’s capital but rather Huế. Her husband was dismissed for a time before being promoted to the position of secretary of the Ministry of Justice. He died prematurely at the age of 43. She had a penchant for Tang versification. This type of poetry is also called ancient poetry because it was used in exams intended to recruit talented people and it was very popular in Vietnam during the period of Northern domination (Tang dynasty).

This type of poem composed of only 8 lines of 7 syllables allows for a total of 8 × 7 = 56 words. Yet the poetess manages to ingeniously describe a magnificent picture focused both on the external landscape and the content. However, this Tang poem has very strict rules and is governed by three essential principles: rhyme, rhythm, and parallelism. Since 1925 in Vietnam, poets no longer adhere to the rules of meter to express themselves freely with the aim of achieving lyricism in each line. But Mme Thanh Quan’s Tang poems must be considered a precious jewel in the Vietnamese literary world. She succeeded in describing and painting a small landscape with 56 words and expressed her deep feelings in a refined manner. She used the Sino-Vietnamese language in a poetic form of 8 lines of 7 syllables with skill. According to researcher Trần Cửu Chấn, a member of the Academy of Letters and Arts of Paris, her Tang poems are considered precious pearls that she selects, polishes, and places on a golden crown or engraved with enamel.

Her poems not only have a classical character but also convey virtuosity in the use of words. She also has the talent to transform lifeless elements such as stone (stone remains impassive over time), water (water shows indignation at the instability of life’s things), or grass and trees (grass and trees intermingle with the rocks while the leaves penetrate among the flowers) into living beings with human nature and soul, and to use dark and light colors to bring out contrasts (Under the pale sky, the evening brings back the shadows of twilight / Yellow shines on the western mountains under the rays of the setting sun) or to bring the past closer to the present ((Lối xưa xe ngựa hồn thu thảo/The old path taken by carriages, the soul of autumn grass wanders there) (Nền cũ lâu đài bóng tịch dương/The remains of the sumptuous palace are illuminated by the rays of the setting sun) (Ngàn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ/ Over the centuries, in this ancient mirror, the past and present are compared). This makes her Tang poems, which describe landscape scenes, like wonderful natural paintings such as watercolors that the artist manages to paint with a brush on silk fabric with shades between dark and light through rigorous observation.

Her Tang poems are highly appreciated by ancient Confucian scholars. Although they only describe the landscape and express her feelings, the terms used are so refined and written by a highly educated aristocratic lady who often thinks of her home and country. This is the commentary of the literary researcher Dương Quảng Hàm. She had a deep attachment to the Lê dynasty but at the same time only expressed the feelings of someone who was not satisfied with the current situation and hoped to regain what existed before. ( Ngàn năm gương cũ soi kim cổ/Cảnh đấy người đây luống đoạn trường) (A thousand years the old mirror reflects the present/That scene, those people, all heartbreaking) (In front of this picture, my entrails feel torn to pieces). The proof is that she accepted the task of teaching the princesses and concubines under the reign of Emperor Minh Mạng of the Nguyễn dynasty. Once, the latter received a new ceramic tea set from China decorated with the landscape of Vietnam. He showed it to his subordinates and asked the poetess to compose a couplet. She quickly improvised the following two lines:

Như in thảo mộc trời Nam lại

Đem cả sơn hà đất Bắc sang.

The grass and trees of the South are visibly reproduced on the ceramics, as well as the mountains and rivers of the North brought there.

Her spontaneity pleased the emperor. It must be acknowledged that the Chinese often pay attention to the mountains and rivers frequently found on decorative objects. In contrast, in Vietnam, the focus is on the lushness of the rice fields. She succeeded in capturing the essence and composing these two parallel verses while strictly respecting the rules of Tang poetry. Upon the death of her husband, a month later, she asked the king to allow her to resign from her position and return to her homeland with her four children. She died in the year 1848 when she was only 43 years old (1805-1848).

Being limited in number (only 6 in total), her poems manage to reflect the noble spirit of the poets and the quintessence of Tang poetry. Composing these poems is already difficult in Chinese characters, but it seems insurmountable in demotic characters since one must also strictly adhere to the rules of Tang poetry. Few people manage to equal her because she knows how to use words with rare linguistic finesse to reveal her solitude and state of mind while relying on the picturesque scenes of nature. She also does not know to whom she can reveal her confidences. (Một mảnh tình riêng ta với ta./Lấy ai mà kể nổi hàn ôn?). She continues to feel regrets and to turn back to the past with her noble mind, constantly thinking of her home and her native land.

THE PASS OF THE GATE OF ANNAM (*)

As I climb the Pass of the Gate of Annam, the shadows of twilight stretch towards the west.

Grass and trees penetrate the rocks, flowers bloom amidst the leaves.

At the foot of the mountain walk some woodcutters, their backs bent under the load;

On the other side of the river rises a market made up of a few scattered huts.

Thinking painfully of the absent homeland, the water’s moan groans without stopping,

Oppressed by attachment to home, the partridge utters uninterrupted cries.

I stop on the path and see around me only sky, mountains, and sea;

Under the weight of this state of mind, I feel alone with myself.

TWILIGHT (*)

Under a pale sky, the evening brings back the shadows of twilight

In the distance, the sound of the watchmen’s horn answers the drum of the guard post.

Laying down his oar, the old fisherman returns to his distant station;

The young herdsman, striking the horns of his buffalo, returns to the solitary hamlet.

The birds fly with effort towards the vast clumps of apricot trees swaying in the wind;

The traveler quickens his pace on the road lined with willows wrapped in mist.

I stay at home; you, you are traveling;

To whom could I confide all my secrets?

(*) Excerpt from the book titled « The Great Poetesses of Vietnam, » Author Trần Cửu Chấn. Thế Giới editions