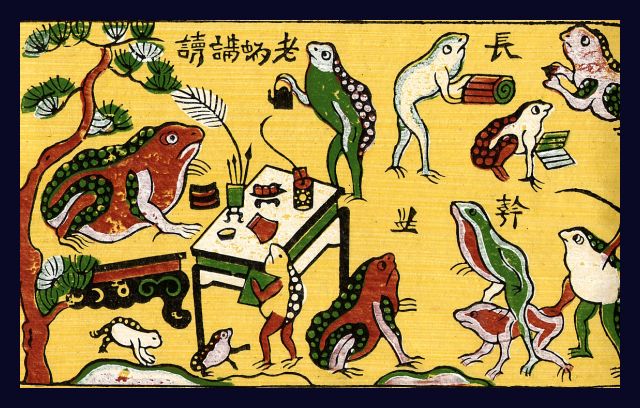

One also retains the outstanding event underlined by the Chinese historian Trịnh Tiều in his work « Thông Chí« : In the southern China, under the reign of Nghiêu king (2253 before J.C.), there was the emissary of a tribe named Việt Thường who offered to the king as a pledge of allegiance, an old tortoise living more than 1000 years and 3 meters long. One found on its back, the inscriptions carrying the characters in the shape of a tadpole (văn Khoa Ðẩu) and allowing to interpret all the changes of the Sky and nature. King Nghiêu decided to attribute to them the name Qui Lịch (or tortoise calendar). This form of writing was recently found on a stone belonging to the cultural vestiges of the region Sapa-Lào Cai in the North of Vietnam. The Vietnamese historian Trần Trọng Kim raised this question in his work entitled Việt Nam sử lược (Abstract of the history of Vietnam). Many clues have been found in favour of the interpretation of the same tribe and people. One cannot refute there is an undeniable bond between the writing in the shape of tadpoles and the toad found either on the bronze drums of Ðồng Sơn or the Ðông Hà popular Vietnamese stamps, the most of which known remains the stamp « Thầy Ðồ Cóc » (or the Master toad). On the latter, one finds the following sentence: Lão oa độc giảng ( the old toad holds the monopoly of teaching ). Although it had appeared 400 years ago only, it ingeniously reflected the perpetual thought of the Hùng vuong time. It is not by chance that one attributed to the toad the Master role but one would like to highlight the importance of the representation and the significance of this image.

The toad was the carrier of a civilization whose the writing in the shape of tadpoles was used by the Lac Viet tribe at the Hùng Vương time because he was the father of the tadpole. In the same way, through the stamp of « Chú bé ôm con cóc » (or the child embraces the toad ), one detected all the original thought of Lạc Việt people. The respect of the child towards the toad or rather its Master (Tôn Sư trọng đạo) was an already existing concept at the Hùng vương time. Could one conclude from it there was a correlation with what one found later in the confucean spirit with the sentence « Tiên học lễ, hậu học văn » ( First learn the moral values then the culture )?

The master toad (Thầy Ðồ Cóc)

In Vietnam, the tortoise is not not only the symbol of longevity and immortality but also that of transmission of spiritual values in the Vietnamese tradition. One finds its representation everywhere, in particular in commonplaces like communal houses, pagodas and temples. It is used at the temple of literature ( Văn Miếu ) to raise steles praising the merits of laureates to the national contests.

The crane on the tortoise back

The crane on the tortoise back

On the other hand, in the temples and communal houses, one sees the tortoise always carry a crane on its back. There is an undeniable resemblance between this crane and the bird wader with a long beak found on the bronze drums of Ðồng Sơn. The crane statue on the tortoise back probably reflects the perpetuity of all the religious beliefs resulting from the Văn Lang civilization through the time.

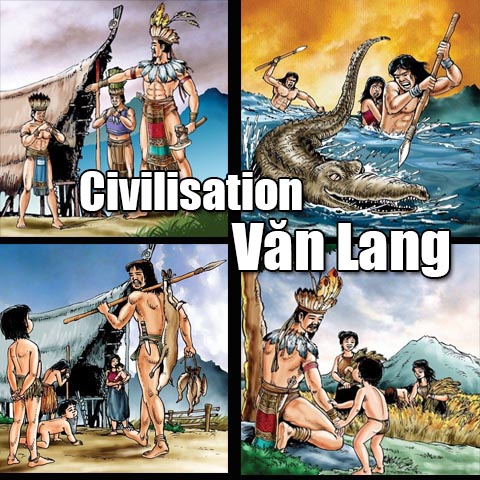

The tortoise omnipresence in the history and culture of the Vietnamese results neither from the long domination of the Chinese nor the effect of chance but it owed to the fact that the Văn Lang kingdom should be located in an area populated by large tortoises. It was only in the south of the Basin Yang Tsé river (Sông Dương Tữ) that one can find this species of large tortoises in extermination. It is what was reported by the Vietnamese author Nguyễn Hiến Lê in his work entitled « Sử Trung Quốc » (History of China ) (Editor Văn Hoá 1996) « .

It is not very probable to find one day, the archaeological vestiges proving the existence of this kingdom like those already found with the Shang dynasty. But nothing invalidates this historical truth because in addition to the facts evoked above, there is even in this kingdom the intangible proof of a very old civilization often named « the Văn Lang civilization » , one found the base of which in the theory of Yin and Yang and the five elements (Thuyết Âm Dương Ngũ Hành ).

Âm Dương

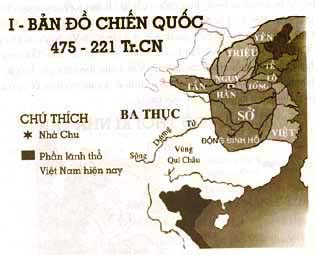

This one was highlighted through the sticky rice cake « Bánh Chưng Bánh dầy » which was exclusively specific to the Vietnamese people since the kings Hùng period. One could raise questions about the origin of this theory which was attributed until now to the Chinese. According to the historical Memoires of Si Ma Qian ( Sử Ký Tư Mã Thiên ), one knew that the philosopher of the country of Qi ( Tề Quốc ) ( 350-270 before J.C.) Tseou Yen (Trâu Diễn), was the first Chinese to highlight the relation between the theory of Yin and Yang and that of the 5 elements ( Wu Xing )(Thuyết Âm Dương Ngũ Hành) at the time of the Warring States (thời Chiến Quốc).

The Yin and the Yang was evoked in the Zhouyi book (Chu Dịch) by the son of king Wen (1)or Duke of Zhou (Chu Công Đán) while the theory of the five elements had been found by Yu the Great (Đại Vũ) of the Xia dynasty ( Hạ ). There was practically an interval of 1000 years between these two theories. The concept of the five elements was quickly integrated into the yin and the yang to give an explanation on the « tao » which is at the origin of everything. In spite of the success met in a great number of domains (astrology, geomancy, traditional medicine), it is difficult to give a coherent justification to the level of the publication date of these theories because the concept Taiji (thái cực) ( supreme limit ) from which the two principal elements were born ( the yin and the yang ), was introduced only at the time of Confucius (500 years before J.C. ). Taiji was the object of meditation for philosophers from all horizons since the philosopher of the Song period and founder of the Neo-Confucianism, Zhou Dunyi ( Chu Ðôn Di ), had given to this concept a new definition in his bestseller: « Treatise on the figure Taiji » ( Thái Cực đồ thuyết ):

Vô cực mà là thái cực, Thái cực động sinh Dương, động đến cực điểm thì tĩnh, tĩnh sinh Âm, tĩnh đến cực đỉnh thì lại động. Một động một tĩnh làm căn bản cho nhau….

From Wuji (no limit) to Taiji (supreme limit or grand extreme). The supreme limit, once in motion, generates the yang and at the limit of motion, it is in the rest state. In turn, this one generates the yin and at the limit of the rest state, it is the return to the motion state. For the latter and the rest state, each takes roots in the other.

For the Chinese, there is a sequence in the beginning of the universe:

Thái cực sinh lưỡng nghi là Âm Dương, Âm Dương sinh Bát Quái

Taiji is the « One » referred to in the Dao principle of creation. From Taiji, Yin and Yang which are the basic attributes of the universe give rise to the eight trigrams.

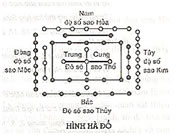

Hà Đồ (Map of the River)

The incoherence is so visible in the chronological order of these theories because one had attributed to Fu Xi (Phục Hi)(1) the invention of the eight trigrams 3500 years ago before J.C. while the concept of Yin and Yang was introduced at the time of Zhou (1200 years before J.C.). While relying on the recent archaeological discoveries, in particular on the discovery of the manuscripts on silk at Mawangdui (1973), the Chinese specialists of today advance unimaginable statements: The hexagrams precede the trigrams…, which proves that the chronological order of these theories is likely to be modified unceasingly in accordance with the new situations. One is brought to find in this imbroglio, an another explanation, an another approach, an another assumption according to which the theory of Yin and Yang and 5 elements was adequated to an another civilization. It would be that of Văn Lang. The confusion continues to be anchored in the reader mind with the famous River map and Writing of Luo (Hà Ðồ Lạc Thư).

The incoherence is so visible in the chronological order of these theories because one had attributed to Fu Xi (Phục Hi)(1) the invention of the eight trigrams 3500 years ago before J.C. while the concept of Yin and Yang was introduced at the time of Zhou (1200 years before J.C.). While relying on the recent archaeological discoveries, in particular on the discovery of the manuscripts on silk at Mawangdui (1973), the Chinese specialists of today advance unimaginable statements: The hexagrams precede the trigrams…, which proves that the chronological order of these theories is likely to be modified unceasingly in accordance with the new situations. One is brought to find in this imbroglio, an another explanation, an another approach, an another assumption according to which the theory of Yin and Yang and 5 elements was adequated to an another civilization. It would be that of Văn Lang. The confusion continues to be anchored in the reader mind with the famous River map and Writing of Luo (Hà Ðồ Lạc Thư).

The Writing of Luo was to be found before the appearance of the Plan of the River. That highlights the contradiction found in the chronological order of these discoveries. Certain Chinese had the occasion to call in question the traditional history established up to that point in the confucian orthodoxy by the Chinese dynasties. It is the case of Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) who saw in this famous plan the work of man. He refuted the « gift from heaven » in his work entitled « Questions of a child about Yi King ( Yi tongzi wen ) » (Zhongguo shudian, Peking 1986). He preferred the version of the human invention.

How can one grant the veracity to the Chinese legend when a complete inconsistency is known in the chronological order of the discovery of these famous Plan of the River and Writing of Luo?

Fou Xi (Phục Hi) (3500 before J.C.) discovered first, the River map ( Hà Ðồ ) at the time of an excursion on the Yellow River (Hoàng Hà). He saw leaving the water a dragon horse (long mã) bearing on its back this plan. It is to You the Great (Đại Vũ) (2205 before J.C.) that one attributed the discovery of the Writing of Luo found on the tortoise back. However it is thanks to the Writing of Luo and with its explanation (Lạc Thư cửu tinh đồ) that one manages to establish and interpret correctly the stellar diagram drawn from the polar star (Bắc Ðẩu) and found on this famous Plan of the river according to the Yin and Yang and 5 elements.

The famous word « Luo » ( Lạc ) found in the text of the Great Commentary of Confucius:

Thị cố thiên sinh thần vật, thánh nhân tắc chi, thiên địa hóa thánh nhân hiệu chi; thiên tượng, hiện cát hung, thánh nhân tượng chi. Hà xuất đồ, Lạc xuất thư, thánh nhân tắc chi

Cho nên trời sinh ra thần vật, thánh nhân áp dụng theo; trời đất biến hoá, thánh nhân bắt chước; trời bày ra hình tượng. Hiện ra sự tốt xấu, thánh nhân phỏng theo ý tượng. Bức đồ hiện ra sông Hoàng Hà, hình chữ hiện ở sông Lạc, thánh nhân áp dụng.

The Heaven gives rise to the divine things, the Wise men take them as criterion. The Heaven and the Earth know changes and transformations, the Wise men reproduce them. The images expressing fortune and misfortune are suspended in the Heaven, the Wise mens imitate them. The Plan comes from the Yellow River, the Writing from the Luo river, the Wise men take them as models.

continues to be interpreted until today like the name of the Luo river, an affluent of the Yellow River which crosses and nourishes the center of China. One continues to see in these famous Plan of the River and Writing of Luo the first premises of the Chinese civilization. From the drawings and figures to the trigrammatic signs, from the trigrammatic signs to the linguistic signs, one thinks of the march of the Chinese civilization in Yi King without believing that it could be the model borrowed by the Wise one from another civilization. However if Luo is associated with the word Yue, that indicates the tribe Lạc Việt (Luo Yue ) from which the Vietnamese come. Does it seem like a sheer coincidence or a name used by the Wise men You the Great or Confucius to refer to the Văn Lang civilization? Lạc Thư indicates effectively the writing of the tribe Luo, Lạc tướng its generals, Lạc điền its territory, Lạc hầu its marquis etc…..

It is rather disconcerting to note that the theory of Yin – Yang and 5 elements finds its perfect cohesion and its functioning in the intangible proof of the Văn Lang civilization, the sticky cake. In addition to the water, one finds in its constitution the 4 essential elements (meat, broad beans, sticky rice, bamboo or latanier leaves). The cycle of generation (Ngũ hành sinh) of 5 elements is quite visible in the making of this cake. At the interior of the cake, one finds a red piece of porkmeat (Fire) surrounded by a kind of paste made with yellow broad beans (Earth). The whole thing is wrapped by the white sticky rice (Metal) to be cooked with boiling water (Water) before finding a green colouring on its surface thanks to the latanier leaves (Wood).

The two geometrical forms, a circle and a square which this cake takes, correspond well to the Yin ( Âm ) and the Yang (Dương). As the Yang breath reflects plenitude and purity, one gives it the shape of a circle. However, one finds in the Yin breath the impurity and limitation. That is why it recovers the form of a square. A light difference is notable in the definition of Yin-Yang of the Chinese and that of the Vietnamese. For the latter, Yin tends to be in motion (động).

Cycle of generation

Fire->Earth->Metal->Water->Wood

Ngũ hành tương sinh

It is for that reason one finds only the presence of the 5 elements in the Yin (Âm) represented by the rice cake in the form of a square ( Bánh chưng ). It is not the case of the cake in the shape of a circle that the Yang (Dương) symbolizes, this latter tending to carry the « motionless » character (tĩnh). It is probably the reason which explains until today why the theory of Yin-Yang and 5 elements does not know a giant leap in its evolution and that its applications continue to carry the mystical and confused character in the public opinion because of the error introduced into the definition of Yin-Yang by the Chinese.

One is accustomed to saying « Mẹ tròn, con vuôn » in Vietnamese to wish the mother and her child a good health at the time of birth. This expression is used as a phrase of courtesy if it is not known that it was bequeathed by our ancestors with an aim of holding our attention on the creative character of the Universe. From this latter were born Yin and Yang which are not only in opposition but also in interaction and correlation. The complementarity and the indissociability of these two poles are at the base of the satisfying development of nature. The typically Vietnamese game « Chơi ô ăn quan » also testifies to the perfect operation of the theory of Yin-Yang and 5 elements. The game stops when one does not find any more tokens in the two extreme half-circles corresponding to the two poles Yin and Yang.

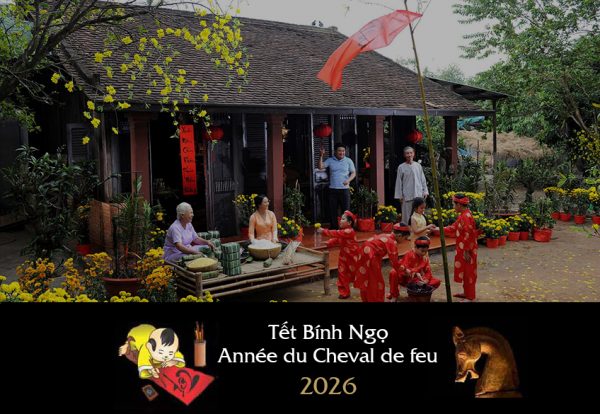

No Vietnamese hides his emotion when he sees on his ancestor altar the sticky rice cake at the time of the Tết festival. For him, this dish looking less attractive and not having any succulent taste, bears a particular significance. It testifies not only to the respect and affection that the Vietnamese likes to maintain with regard to his ancestors but also the impression of a 5000-year old civilization. This sticky rice cake is the undeniable proof of the perfect functioning of Yin and Yang and 5 elements. It is the only intact legacy that the Vietnamese succeeded in receiving on behalf of his ancestors in the swirls of history. It cannot compete with the masterpieces of other civilizations like the Wall of China or pyramids of the Pharaohs built with sweat and blood. It is the living symbol of a civilization which bequeathed to humanity a knowledge of priceless value. One continues to use it in a great number of domains of application (astronomy, geomancy, medicine, astrology etc….). Return to Part 1