Version vietnamienne

English version

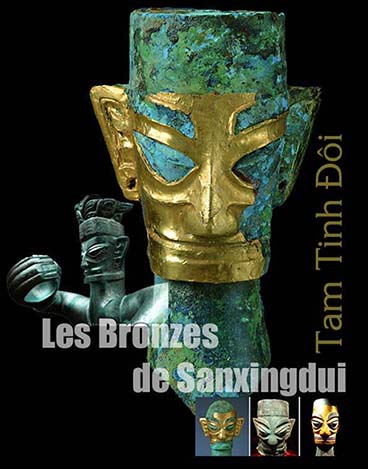

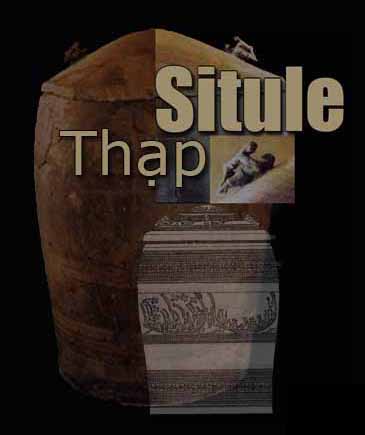

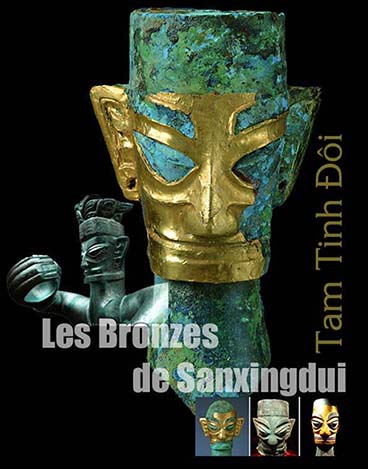

Depuis la découverte d’un grand nombre d’éléments de jade par le hasard à partir d’un coup de pioche effectué en 1929 par un fermier, suivie ensuite par les deux fouilles sacrificielles en 1986 par les archéologues chinois, Sanxingdui révèle un pan inconnu de la civilisation de Sichuan. Jusqu’alors, selon les textes chinois, la civilisation chinoise émerge seulement dans la plaine centrale dont le cœur antique reste Anyang, l’ancienne capitale des Shang. C’est dans l’historiographie traditionnelle, que Yu le Grand, (Đại Vũ) le dompteur des eaux et le fondateur de la dynastie mythique des Xia, aurait le mérite d’inventer la métallurgie dans la vallée du fleuve jaune. Désormais, les archéologues sont obligés de réévaluer leurs idées sur les premiers développements de l’âge du bronze car il y avait à cette époque d’autres foyers de civilisation aussi originaux et contemporains des Shang.

L’image idéale d’une civilisation chinoise issue d’Anyang (An Dương) s’effrite depuis la découverte du site Sanxingdui car ce dernier, situé dans une périphérie barbare, révèle une culture aussi sophistiquée que celle des Shang et ignorée jusque-là par les historiens chinois et par les écrits. Selon l’expert en archéologie Task Rosen du « British Museum », la découverte de la culture de Sanxingdui semble être plus remarquable que celle des guerriers et des chevaux en terre cuite de Qin Shi Huang Di à Xian. Les quatre plaques incrustées de turquoise et trouvées dans la fosse de Sanxingdui sont très similaires à celles rencontrées dans la région d’Erlitou (province de Henan) que les archéologues ont considéré jusqu’alors comme le berceau de la culture du bronze chinois. Cette parenté témoigne évidemment de l’échange commercial et de la transmission de savoirs techniques sophistiqués de la plaine centrale vers le Sichuan. Cette région du cours moyen du fleuve Bleu (ou Yangzi Jiang)(Dương Tữ Giang) a joué peut-être, selon le sinologue Alain Thote, le relais dans cette transmission.

Les résultats de l’analyse isotopique du plomb dans le bronze, que ce soit celui du site Sanxingdui, de la tombe de la reine guerrière Fu Hao (Phụ Hảo) de la dynastie des Shang à Anyang (An Dương) dans la province de Henan ou de Xin’gan au Jiangxi confirment la présence irréfutable du même plomb venant de la province de Yunnan. Dans ces trois régions, la technique de fabrication est la technique de la fonte renversée dans des moules d’argile segmentés, née au XVIème siècle avant notre ère dans la culture d’Erlitou (Période Xia?)(Nhà Hạ). Sur la base de ces résultats, on est amené à supposer que ces échanges aient été établies entre différentes régions vers le milieu du IIème millénaire avant J.C. Les interactions culturelles ne sont plus mises en doute sur une vaste étendue de la Chine ancienne. Les Shang n’étaient pas les seuls à détenir le pouvoir universel comme cela a été donné par les écrits chinois mais ils avaient des voisins aussi puissants qu’eux et avec lesquels ils échangeaient des liens plus ou moins étroits.

Situé à une quarantaine de kilomètres au nord de la capitale Chengdu (Thành Đô) de Sichuan, le site archéologique Sanxingdui, proche de la ville de GuangHan (Quãng Hán) est désigné au début comme un endroit de terre damée où se trouve la formation de trois buttes (Trois Etoiles). C’est seulement lors de la découverte des deux célèbres fosses en 1986 que les archéologues commençaient à s’intéresser à ce site qui, grâce à la fouille en 1996, se révélerait être l’ancienne occupation d’une cité remontant aux environs de 1800 avant J.C. et s’étendant sur une dizaine de kilomètres. Ces deux fosses sont situées à trente mètres l’une de l’autre et ont chacune une profondeur d’environ 1,5 m et un écart d’âge de quelques décennies (30 ans au moins).

La première contient un total de 420 objets, des fragments d’os carbonisés, de défenses d’éléphants, de coquillages marins (cauris) etc. tandis que dans la deuxième il y a non seulement un nombre de pièces trois fois plus important (1300 environ) mais aussi des pièces imposantes (une gigantesque statue verticale et mince en bronze, , des arbres sacrés en bronze et des masques anthropomorphes). Aucun ordre précis n’est établi lors du dépôt de ces pièces. Par contre ces offrandes regroupées par catégories d’objets, ont été brisées et brûlées volontairement en grande partie dans les fosses. Parmi les trouvailles archéologiques du site Sanxingdui, les plus beaux éléments restent la statue d’un personnage monumental haut d’environ 1,71 m et debout sur un socle à décor masqué (constitué de quatre masques têtes d’animaux renversés) et portant selon certains archéologues, dans ses mains disproportionnées, soit un ou des objets de forme cylindrique soit une défense d’éléphant et un arbre des esprits en bronze brisé, pouvant atteindre 4 m de haut dans sa reconstitution et relatant le culte du soleil.

Mais ce sont plutôt les masques saisissants de bronze qui retiennent l’attention des archéologues lors la fouille de la fosse sacrificielle n°2 car ces têtes de bronze ont chacune un aspect plus grotesque que les figures humaines, de grandes oreilles d’éléphants, un nez droit, un visage carré, une bouche étroite occupant la largeur du visage et des yeux un peux exagérés ayant la forme de la graine de l’amande. On en a retrouvé treize au total au moment de la découverte de cette fosse.

Contrairement aux Shang laissant des inscriptions sur leurs bronzes, le site de Sanxingdui n’a donné aucune trace écrite. Les archéologues ont été contraints de lui attribuer méthodiquement le caractère profondément religieux et sacrificiel. Leur justification s’appuie d’abord sur un faisceau dense de croyances à travers les masques, les créatures hybrides entre l’homme et la bête, les dragons, les hommes-oiseaux, les objets rituels trouvés dans les fosses, puis sur l’absence d’ornements et l’état des offrandes délibérément détruites et rendues inutilisables et surtout sur le tassement de la terre de remblai en plusieurs couches marquant l’intention de vouloir sceller pour toujours ce site. Selon Niannian Fan, un scientifique spécialisé dans l’étude des rivières à l’université de Sichuan (Chengdu), le site Sanxingdui a été enseveli par le glissement du terrain dû à la montée et descente hâtive du lit de la rivière Minjiang lors d’un séisme majeur ayant eu lieu il y a plus de 3000 ans.

Niannian Fan tente de conforter son hypothèse en trouvant dans les anciens écrits historiques, un catastrophe majeur survenu en 1099 dans la capitale des Zhou (Shaanxi). Pour lui, les habitants de Sanxingdui furent obligés de transférer à cette époque leur cité à Jinsha, distant de 50 km de Sanxingdui et situé sur les berges de la rivière Modi. Malgré cela, l’hypothèse du séisme et du glissement du terrain n’est pas très convaincant car il ne peut pas expliquer les raisons pour lesquelles les objets rituels ont été cassés délibérément avant d’être jetés dans les fosses de Sanxingdui à l’époque où ce dernier fut abandonné.

Selon le sinologue français Alain Thote, du fait de ses débordements, la rivière traversant le site était certainement responsable de la disparition d’une partie des vestiges située au cœur de la cité Sanxingdui. Outre les raisons inconnues de l’abandon précipité du site Sanxingdu et de son futur remplacement par le site Jinsha découvert en 1996 dans la banlieue ouest de Chengdu, la découverte continue à être empreinte de mystère et éveiller l’intérêt et la soif de la connaissance de la vérité. Certains objets ont trouvé une explication probante, d’autres restant en suspens jusqu’à aujourd’hui. Depuis longtemps, on a cru que le royaume de Shu (Thục Quốc) appartenait à la légende mais la découverte de Sanxingdui révèle désormais non seulement son existence datant d’au moins de 5000 ans à 3000 ans mais aussi la complexité de ses rites à travers ses artefacts fascinants et étranges. Ceux-ci sont principalement les têtes humaines fabriquées dans un système très élaboré de conventions propres à l’art de Sanxingdui dans le but de les mettre à distance par rapport au monde réel et d’éviter de refléter exactement ce dernier.

Par contre, aucun souci d’individualisation n’est trouvé dans toutes ces têtes. La fosse n°1 contenait 13 têtes humaines en bronze tandis que dans la deuxième fosse, il y avait quarante quatre dont quatre étaient partiellement recouvertes d’une feuille d’or. De faible épaisseur, celle-ci était découpée et incisée ou martelée selon une technique proche du repoussé. Sa présence est décelée soit sur les ornements de l’arbre en bronze, soit sur les masques ou sur une canne longue de 142 cm dans les deux fosses de Sanxingdui et sur le site de Jinsha. En l’état des connaissances des archéologues, les feuilles d’or associées aux objets rituels étaient à la fois minces, légères et assez peu décorées. De plus, l’or n’était pas fondu à la cire perdue. Ce matériau précieux provenait probablement des gisements aurifères de Sichuan connue autrefois comme une région riche en ressources minières. C’est l’une des caractéristiques de l’art de Sanxingdui car l’or n’était pas utilisé encore à la fin du IIème millénaire avant notre ère à la capitale Anyang des Shang contemporains dans leur art.

Lame de cérémonie zhang (Nha chương)

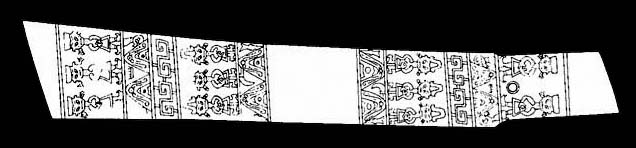

Connues sous le nom de « zhang », les lames en jade ou taillées dans des pierres ayant l’aspect du jade se terminent en une ou deux pointes et constituent la deuxième caractéristique trouvée dans l’art de Sanxingdui. Leur possession témoigne de l’appartenance à un certain rang dans la société de Sanxingdui. Elles semblaient revêtir à cette époque, une importance particulière dans les cérémonies rituelles réservées aux élites de Sanxingdui. Ces dernières devaient s’en servir en les prenant à deux mains en avant de leur poitrine, dans une attitude déférente en présence du roi ou dans un geste d’offrande devant les dieux. Selon le sinologue Alain Thote, rien n’est permis de trancher encore entre ces deux théories.

Leur emploi connut un succès inouï révélé à Sanxingdui par la multitude des formes et l’enrichissement du décor finement incisé à l’aiguille. Cela témoigne incontestablement de la volonté de développer une recherche esthétique très poussée et de la créativité originale dans leur réalisation par rapport aux zhang trouvés en Chine du Nord et du Centre. Pourtant, selon l’étude de la carte des découvertes, associée à une analyse chrono-typologique, on sait que cette pièce est originaire de la Chine du Nord et elle est absente sur les sites de la région du cours moyen du fleuve Bleu. Cela conforte l’hypothèse d’une transmission directe de cet objet rituel, de la plaine centrale à Sichuan au cours du deuxième millénaire pour laisser à la fin de sa diffusion, aux élites de Sanxingdui, la prééminence d’en faire un très large usage.

[Les bronzes de Sanxingdui: Partie 2(Suite)]

English version

Since the discovery of a large number of jade items by chance from a pickaxe strike made in 1929 by a farmer, followed by two sacrificial excavations in 1986 by Chinese archaeologists, Sanxingdui reveals an unknown aspect of the Sichuan civilization. Until then, according to Chinese texts, Chinese civilization only emerged in the central plain, whose ancient heart remains Anyang, the former capital of the Shang. In traditional historiography, Yu the Great (Đại Vũ), the tamer of waters and founder of the mythical Xia dynasty, is credited with inventing metallurgy in the Yellow River valley. From now on, archaeologists are forced to reassess their ideas about the early developments of the Bronze Age because at that time there were other centers of civilization as original and contemporary as the Shang.

The ideal image of a Chinese civilization originating from Anyang (An Dương) has been eroding since the discovery of the Sanxingdui site because the latter, located in a barbaric periphery, reveals a culture as sophisticated as that of the Shang and previously ignored by Chinese historians and writings. According to archaeology expert Task Rosen from the British Museum, the discovery of the Sanxingdui culture seems to be more remarkable than that of the terracotta warriors and horses of Qin Shi Huang Di in Xian. The four turquoise-inlaid plaques found in the Sanxingdui pit are very similar to those encountered in the Erlitou region (Henan province), which archaeologists had until now considered the cradle of Chinese bronze culture.

This kinship obviously testifies to commercial exchange and the transmission of sophisticated technical knowledge from the central plain to Sichuan. This region of the middle course of the Blue River (or Yangzi Jiang) (Dương Tữ Giang) may have played, according to sinologist Alain Thote, a relay role in this transmission. The results of isotopic analysis of lead in the bronze, whether from the Sanxingdui site, the tomb of the warrior queen Fu Hao (Phụ Hảo) of the Shang dynasty at Anyang (An Dương) in Henan province, or Xin’gan in Jiangxi, confirm the irrefutable presence of the same lead coming from Yunnan province.

In these three regions, the manufacturing technique is the inverted casting method in segmented clay molds, which originated in the 16th century BCE in the Erlitou culture (Xia Period?)(Nhà Hạ). Based on these results, it is assumed that these exchanges were established between different regions around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. Cultural interactions are no longer in doubt across a vast expanse of ancient China. The Shang were not the only ones holding universal power as stated in Chinese writings, but they had neighbors as powerful as themselves with whom they exchanged more or less close ties.

Located about forty kilometers north of the capital Chengdu (Thành Đô) in Sichuan, the Sanxingdui archaeological site, near the city of GuangHan (Quãng Hán), was initially designated as a place of compacted earth where three mounds (Three Stars) are found. It was only with the discovery of the two famous pits in 1986 that archaeologists began to take an interest in this site, which, thanks to excavations in 1996, revealed itself to be the ancient occupation of a city dating back to around 1800 BCE and covering about ten kilometers. These two pits are located thirty meters apart from each other, each about 1.5 meters deep, and have an age difference of a few decades (at least 30 years).

The first contains a total of 420 objects, including fragments of charred bones, elephant tusks, marine shells (cowries), etc., while the second not only has about three times as many pieces (around 1300) but also large items (a gigantic vertical and slender bronze statue, sacred bronze trees, and anthropomorphic masks). No specific order was established during the deposition of these pieces. However, these offerings, grouped by categories of objects, were largely broken and deliberately burned in the pits. Among the archaeological finds at the Sanxingdui site, the most beautiful elements remain the statue of a monumental figure about 1.71 meters tall, standing on a base decorated with masks (consisting of four overturned animal head masks) and holding, according to some archaeologists, in its disproportionate hands either one or several cylindrical-shaped objects or an elephant tusk and a broken bronze spirit tree, which can reach up to 4 meters tall in its reconstruction and relates to the sun cult.

But it was the striking bronze masks that captured the archaeologists’ attention during the excavation of Sacrificial Pit No. 2. Each of these bronze heads had a more grotesque appearance than the human figures, with large elephant ears, a straight nose, a square face, a narrow mouth spanning the width of the face, and slightly exaggerated eyes shaped like almond seeds. A total of thirteen were found at the time of this pit’s discovery.

Unlike the Shang, who left inscriptions on their bronzes, the Sanxingdui site yielded no written records. Archaeologists were forced to methodically attribute to it a profoundly religious and sacrificial nature. Their justification is based first on a dense bundle of beliefs through masks, hybrid creatures between man and beast, dragons, bird-men, ritual objects found in the pits, then on the absence of ornaments and the state of the offerings deliberately destroyed and rendered unusable and especially on the compaction of the earth of embankment in several layers marking the intention to want to seal forever this site. According to Niannian Fan, a scientist specialized in the study of rivers at the University of Sichuan (Chengdu), the Sanxingdui site was buried by the landslide due to the hasty rise and fall of the bed of the Minjiang River during a major earthquake that took place more than 3000 years ago.

Niannian Fan attempts to support his hypothesis by finding in ancient historical writings a major disaster that occurred in 1099 in the Zhou capital (Shaanxi). According to him, the inhabitants of Sanxingdui were forced to relocate their city to Jinsha at that time, 50 km from Sanxingdui and located on the banks of the Modi River. Despite this, the earthquake and landslide hypothesis is not very convincing because it cannot explain why ritual objects were deliberately broken before being thrown into the Sanxingdui pits at the time when the city was abandoned.

According to French sinologist Alain Thote, due to its overflowing, the river flowing through the site was certainly responsible for the disappearance of part of the remains located in the heart of the Sanxingdui city. Apart from the unknown reasons for the hasty abandonment of the Sanxingdu site and its eventual replacement by the Jinsha site discovered in 1996 in the western suburbs of Chengdu, the discovery continues to be shrouded in mystery and to arouse interest and a thirst for knowledge of the truth. Some objects have found a convincing explanation, others remain unresolved until today. For a long time, it was believed that the kingdom of Shu (Thục Quốc) belonged to legend but the discovery of Sanxingdui now reveals not only its existence dating back at least 5000 years to 3000 years but also the complexity of its rites through its fascinating and strange artifacts. These are mainly the human heads made in a very elaborate system of conventions specific to the art of Sanxingdui in order to distance them from the real world and to avoid reflecting it exactly.

On the other hand, no concern for individualization is found in all these heads. Pit No. 1 contained 13 bronze human heads while in the second pit, there were forty-four, four of which were partially covered with gold leaf. Thin, this was cut and incised or hammered using a technique close to repoussé. Its presence is detected either on the bronze tree ornaments, or on the masks or on a 142 cm long cane in the two pits of Sanxingdui and on the site of Jinsha. According to the state of knowledge of archaeologists, the gold leaves associated with ritual objects were both thin, light and relatively undecorated. Moreover, the gold was not melted using the lost wax method. This precious material probably came from the gold deposits of Sichuan, formerly known as a region rich in mineral resources. This is one of the characteristics of Sanxingdui art because gold was not yet used in their art at the end of the 2nd millennium BC in the contemporary Shang capital of Anyang.

Known as « zhang, » blades made of jade or jade-like stones end in one or two points and constitute the second characteristic found in Sanxingdui art. Their possession indicates belonging to a certain rank in Sanxingdui society. At this time, they seemed to have held particular importance in ritual ceremonies reserved for the elites of Sanxingdui. The latter were to use them by holding them with both hands in front of their chest, in a deferential attitude in the presence of the king or in a gesture of offering before the gods. According to sinologist Alain Thote, there is still no definitive answer between these two theories.

Their use enjoyed unprecedented success in Sanxingdui, revealed by the multitude of forms and the enrichment of the finely incised needlework. This undoubtedly demonstrates the desire to develop a very advanced aesthetic research and the original creativity in their realization compared to the zhang found in North and Central China. However, according to the study of the map of the discoveries, associated with a chrono-typological analysis, we know that this piece originates from North China and it is absent on the sites of the region of the middle course of the Blue River. This supports the hypothesis of a direct transmission of this ritual object, from the central plain to Sichuan during the second millennium to leave at the end of its diffusion, to the elites of Sanxingdui, the preeminence to make a very wide use of it.

[The Sanxingdui Bronzes: Part 2(Continued)]

Références bibliographiques

Références bibliographiques

Re-examination of the artifact pits of Sanxingdui. Shi Jingsong. Chinese archeology

New research exploring the origins of Sanxingdui. Rowan Flad. Backdirt 2008

Art et archéologie de la Chine impériale. Alain Thote, Robert W. Bagley. Livret annuaire 2002-2003-2004, pp 362-369

La redécouverte de la Chine ancienne. Corinne Debaine-Francfort. Découvertes Gallimard.