Một mảnh hồn của đất nước

Part 1

Version française

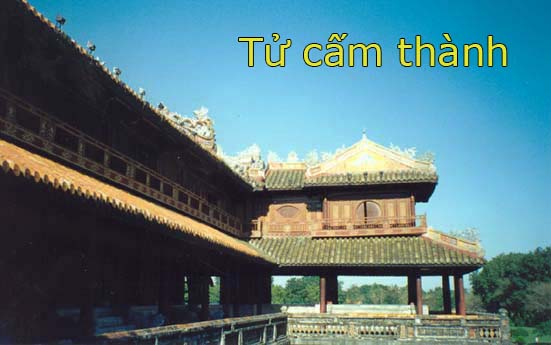

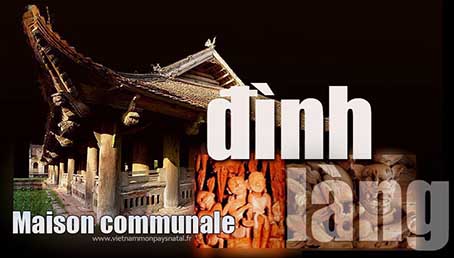

Đình Làng

These are two words that it is difficult to separate in the spirit of the Vietnamese because everywhere there is a Vietnamese village, there is also somewhere a communal house, a « đình ». This one, always covered with tiles, is a wooden colossal building on stilts. Unlike the pagoda which closes itself off, the « đình » has neither doors nor wall and communicates directly with the outside world. Its imposing wide roof cannot go undetected with its super elevated edges ( đầu đao ). Its location is the subject of meticulous studies of geomancy. Its construction is carried out in most cases on a fairly high terrain considered as a sacred space and it is oriented so as to have access to a water piece (lake, river , wells) with the aim of gathering the peak of well-being. (Tụ thủy, tụ linh, tụ phúc).

This is the case of the đình Tây Ðằng with a water piece filled with lotus in front of its porch in summer or the đình Ðồng Kỵ ( Từ Sơn, Bắc Ninh) erected in front of a river or that of Lệ Mật (Gia Lâm, Hànội) with a wide well. The Vietnamese communal house is often built within a green surroundings with the centuries-old banyan trees, frangipani, palm trees etc. ..

We cannot define better its role than that which has been summarily written by French Paul-Giran in his book entitled: Magie et Religion annamites, pp 334-335, 1912:

The đình where lives the genius protector of each village (thành hoàng) is the centre of the community’s collective life. It is here that there are the meetings of village notables allowing them to address the administration and justice issues. It is also here that one can see religious ceremonies and acts that are the life of the Vietnamese society.

We can say that it is somehow the town hall of a city today. But it is better considered that the latter because it is the strong emotional bond with the entire community of the village. Through it, the Vietnamese can regain not only his roots but also the aspirations and shared memories of the village where he was born and he grew up. His deep attachment to his village, in particular his « đình », is not breaking the expression of his feelings that we usually find in popular songs:

Qua đình ngả nón trông đình

Ðình bao nhiêu ngói thương mình bấy nhiêu….

Passing by, she doffs her hat towards the communal house

The đình possess many tiled roof as much as she loves you…

or

Trúc xinh trúc mọc đầu đình

Em xinh em đứng một mình cũng xinh

……………………………

Bao giờ rau diếp làm đình

Gỗ lim ăn ghém thì mình lấy ta ….

The beautiful bamboo grows at the entrance of the communal house

You are nice, my sweetheart even if you are alone

……………………………………….

Whenever lettuce can be used to build a communal house

and wood « lim » comestible, we could be married …

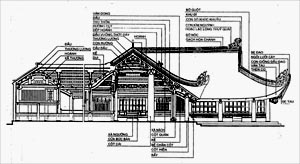

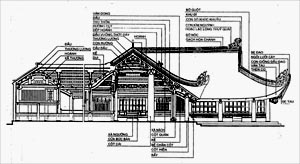

The image of the communal house is intimately rooted in the heart of the Vietnamese. The đình is the symbol of their identity. Already, in the XII century, under Lý dynasty, an edict stated that on all the Vietnamese territory, each village must build its own đình. This one followed the Vietnamese during their advancement to the south from the XIth to the XVIIIth century. Firstly, it was implemented in the center of Vietnam through Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An provinces under Lê dynasty and then Thuận Hóa and Quảng Nam provinces under Mạc dynasty and finally in the Mekong delta at the point of Cà Mau with Nguyễn lords. Its construction evolved to adapt not only to new climate, new lands acquired and new materials available found on local site but also traditions and regional customs throughout entire course over thousands of kilometers during the four centuries of expansion. Except the Central Highlands, cradle of the ancestral culture of ethnic minorities, the « đình » succeeds to distinguish itself in diversity with a style and a own architecture for each district within each region. Built a few centuries earlier, the « đình » in the North remains the reference for the majority of Vietnamese because it is chosen not for its aesthetic character but rather for its original character. It is the authentic symbol of rural life of the Vietnamese people over the centuries. It has been erected the first by Vietnamese village culture in the Red River delta. The đình in the north is not only an assembly of columns, main rafters and all sorts of components joined by mortises and tenons on stone foundation but it is also a wooden frame on which is based the roof reinforced by its own weight. One of the characteristics of Vietnamese communal house is found in the role of the columns used to sustain the roof. Its look is very imposing thanks to these large main columns.

Communal house Ðình Bảng ( Tiên Sơn, Bắc Ninh )

This is the case of đình Yên Đông destroyed by fire (Quảng Ninh) and main columns of which reach 105 cm in diameter. This impression is often illustrated by the expression that one has the habit of saying in Vietnamese: to như cột đình (colossal as the column of the đình ). That is what one see in the famous « Ðình Bảng » with its 60 wooden columns (gỗ lim) and its large roof completed by the edges elevated in the form of lotus petals. READING MORE

Đình Mông Phụ (Sơn Tây)