Thời kỳ Hồng Bàng

Version anglaise

Version vietnamienne

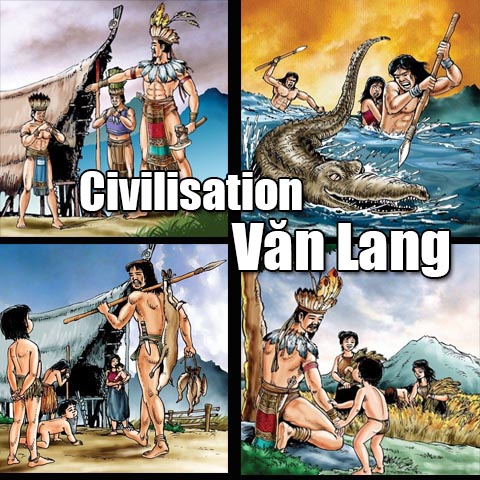

Période Văn Lang

Les Vietnamiens ont l’habitude de dire: l’eau bue nous rappelle la source (Uống nước nhớ nguồn). Rien n’est étonnant de les voir continuer à fêter en grande pompe au 10ème jour du troisième mois lunaire de chaque année la journée de commémoration des rois Hùng de la dynastie des Hồng Bàng, les pères fondateurs de la nation vietnamienne. Jusqu’à aujourd’hui, aucun vestige archéologique n’est trouvé pour confirmer l’existence de cette dynastie à part les ruines de la citadelle Cổ Loa ( Cité du coquillage ) datant de l’époque de règne du roi An Dương Vương, le temple édifié en l’honneur de ces rois Hùng à Phong Châu ainsi que les lames de jade (Nha chương) dans la province de Phú Thọ.

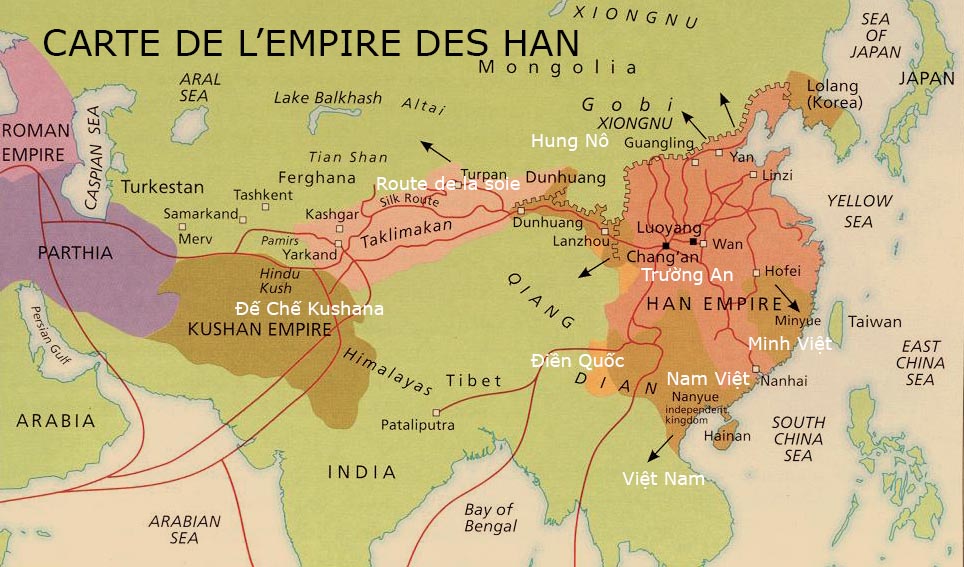

Beaucoup d’indices n’infirment pas cette existence si on se réfère aux légendes rapportées de cette époque mythique et aux Annales du Vietnam et de la Chine. La domination chinoise ( IIIème siècle avant J.C.- 939 après J.C. ) n’est pas étrangère à l’influence la plus grande sur le développement de le civilisation vietnamienne. Tout ce qui appartient aux Vietnamiens devient chinois et vice-versa durant cette période. On constate une politique d’assimilation délibérément voulue par les Chinois. Cela ne laisse pas aux Vietnamiens la possibilité de maintenir leur culture héritant d’une civilisation vieille de 5000 ans et dénommée « civilisation de Văn Lang » sans recourir aux traditions orales (les proverbes, les poèmes populaires ou les légendes).

Le recours à l’allusion mythique est le moyen le plus sûr de permettre à la postérité de retrouver son origine en lui donnant un grand nombre d’indices utiles malgré la destruction systématique de leur culture et la répression inexorable des Chinois à l’encontre des Yue (ou des Vietnamiens). Pour le chercheur Paul Pozner, l’historiographie vietnamienne se base sur une très longue et permanente tradition historique. Celle-ci est représentée par une tradition historique orale durant plusieurs siècles du premier millénaire avant notre ère sous forme de légendes historiques dans les temples des cultes des ancêtres (1).

Les deux vers trouvés dans la chanson populaire (ca dao) suivante :

Trăm năm bia đá thì mòn

Ngàn năm bia miệng vẫn còn trơ trơ

Avec cent ans, la stèle de pierre continue à se détériorer

Avec mille ans, les paroles des gens continuent à rester en vigueur

témoignent de la pratique menée sciemment par les Vietnamiens dans le but de préserver ce qu’ils ont eu de la civilisation de Văn Lang.

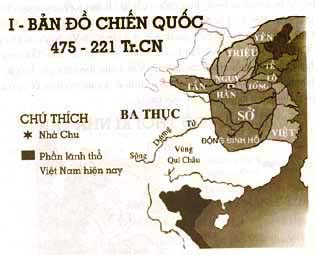

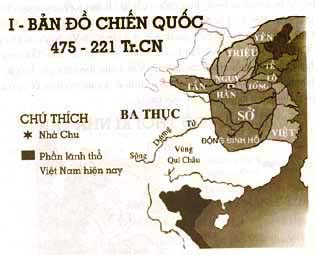

Celle-ci porte le nom d’un royaume bordé à cette époque au nord par Nam Hải,(Nanhai), à l’ouest par le royaume de Ba Thuc (Tứ Xuyên ou Sichuan en français), au nord par le territoire du lac Ðộng Ðình (Hu Nan) (Hồ Nam) et au sud par le royaume de Hồ Tôn (Champa). Ce royaume était situé dans le bassin du fleuve Yang tsé (Sông Dương Tử) et était placé sous l’autorité d’un roi Hùng. Celui-ci avait été élu pour son courage et ses valeurs. Il avait partagé son royaume en districts confiés à ses frères connus sous le nom « Lạc hầu » (marquis). Ses enfants mâles avaient le titre de Quan lang et ses filles celui de Mỵ nương. Son peuple était connu sous le nom Lạc Việt. Ses hommes avaient pour coutume de se tatouer le corps. Cette pratique « barbare », révélée souvent dans les annales chinoises, était si l’on croit les textes vietnamiens, destinée à protéger les hommes des attaques des dragons d’eau (con thuồng luồng).

C’est peut-être la raison que les Chinois les désignaient souvent sous le nom Qủi (démons). Pagne et chignon constituaient le costume habituel de ce peuple auquel étaient ajoutées des parures en bronze. Les Lạc Việt se laquaient les dents en noir, chiquaient du bétel et pilaient du riz à la main. Agriculteurs, ils pratiquaient la culture du riz en champ inondé.

Ils vivaient dans les plaines et les régions littorales tandis que dans les régions montagneuses du Việt Bắc et sur une partie du territoire de la province chinoise de Kouang Si, se réfugiaient les Tây Âu, les ancêtres des groupes ethniques Tây, Nùng et Choang. Vers la fin du troisième siècle avant notre ère, le chef des tribus Tây Âu défit le dernier roi Hùng et réussit à réunifier sous sa bannière les territoires des Tây Âu et celui des Lạc Việt pour former le royaume de Âu Lạc, en l’an 258 avant notre ère. Il prit comme nom de règne An Dương Vương et transféra sa capitale à Cổ Loa située à une vingtaine de kilomètres de Hanoï.

Le royaume de Văn Lang est-il une pure invention alimentée par les Vietnamiens dans le but d’entretenir un mythe ou un royaume réellement existant et disparu dans les tourbillons de l’histoire?

Carte géographique du royaume Văn Lang

Selon le mythe vietnamien, le pays de ces Proto-Vietnamiens était délimité au Nord à l’époque des Hùng Vương (première dynastie des Vietnamiens 2879 avant J.C.) par le lac de Dongting (Động Đình Hồ) situé dans le territoire du royaume de Chu (Sở Quốc). Une partie de leur territoire revint à ce dernier à l’époque des Royaumes Combattants (thời Chiến Quốc). Leurs descendants vivant dans cette partie rattachée devinrent probablement les sujets du royaume de Chu. Il y avait évidemment un rapport, un lien intime entre ce royaume et les Proto-Vietnamiens. C’est une hypothèse suggérée et avancée récemment par un écrivain vietnamien Nguyên Nguyên(2). Selon celui-ci, il n’est pas rare que dans les textes anciens, les idéogrammes soient remplacés par d’autres idéogrammes avec la même phonétique. C’est le cas du titre Kinh Dương Vương qu’avait pris le père de l’ancêtre des Vietnamiens, Lôc Tục. En l’écrivant de cette manière en chinois,  on voit apparaître facilement les noms de deux villes Kinh Châu (Jīngzhōu)(3) et Dương Châu (Yángzhōu)(4) où vivaient respectivement les ethnies des Yue de branche Thai et de branche Lạc. Il y avait la traduction d’une volonté d’évoquer intelligemment par le narrateur l’implantation et la fusion des ethnies yue de branche Thai (Si Ngeou) et de branche Lac (Ngeou-lo) provenant des migrations de ces villes lors des conquêtes d’annexion de Chu. Par contre, l’idéogramme 陽 (thái dương) se traduit comme lumière, solennel.

on voit apparaître facilement les noms de deux villes Kinh Châu (Jīngzhōu)(3) et Dương Châu (Yángzhōu)(4) où vivaient respectivement les ethnies des Yue de branche Thai et de branche Lạc. Il y avait la traduction d’une volonté d’évoquer intelligemment par le narrateur l’implantation et la fusion des ethnies yue de branche Thai (Si Ngeou) et de branche Lac (Ngeou-lo) provenant des migrations de ces villes lors des conquêtes d’annexion de Chu. Par contre, l’idéogramme 陽 (thái dương) se traduit comme lumière, solennel.

Il est utilisé dans le but d’éviter son emploi en tant que nom de famille. En se servant de ces mots, cela permet de traduire Kinh Dương Vương en roi solennel Kinh. Mais il y a également un mot Kinh

en roi solennel Kinh. Mais il y a également un mot Kinh  synonyme du mot Lac (

synonyme du mot Lac ( ), surnom des Viêt. Bref, Kinh Dương Vương peut se traduire comme le Roi solennel Viêt. Quant au titre An Dương Vương qu’a pris le roi de Âu Viêt, l’auteur ne met pas en doute son explication: il s’agit bien de la pacification du pays des Yue de branche Lac (trị an xứ Dương) par un fils de Yue de branche Thái.

), surnom des Viêt. Bref, Kinh Dương Vương peut se traduire comme le Roi solennel Viêt. Quant au titre An Dương Vương qu’a pris le roi de Âu Viêt, l’auteur ne met pas en doute son explication: il s’agit bien de la pacification du pays des Yue de branche Lac (trị an xứ Dương) par un fils de Yue de branche Thái.

Cela ne peut que conforter la thèse d’Edouard Chavannes (5) et de Léonard Aurousseau(5): les Proto-Vietnamiens et les sujets du royaume de Chu ont les mêmes ancêtres. De plus il y a une coïncidence étonnante trouvée dans le nom de clan Mị (咩)(bêlement du mouton) et porté par les rois de Chu et celui des rois vietnamiens. En se basant sur les Mémoires historiques (Che-Ki) de Sseu-Ma Tsien (Tư Mã Thiên) traduites par E. Chavannes (6), on sait que le roi de la principauté Chu est issu des barbares du Sud (ou Bai Yue) : Hiong-K’iu (Hùng Cừ) dit : Je suis un barbare et je ne prends point part aux titres et aux noms posthumes des royaumes du Milieu.

Les linguistes américains Mei Tsulin (6) et Norman Jerry ont identifié un certain nombre de mots d’emprunt de la langue austro-asiatique des Yue dans les textes chinois de la période des Han.

C’est le cas du mot chinois jiang 囝 (giang en vietnamien ou rivière en français) ou le mot nu (ná  en vietnamien ou arbalète en français). Ils ont démontré la forte probabilité de la présence de la langue austro-asiatique dans la Chine du Sud et ont conclu qu’il y avait eu un contact entre la langue chinoise et la langue austro-asiatique dans le territoire de l’ancien royaume de Chu entre 1000 et 500 ans avant J.C. Cet argument géographique n’était jamais pris en compte sérieusement dans le passé par certains historiens vietnamiens car pour eux, cette dynastie relevait plutôt de la période mythique. De plus, d’après les sources chinoises, le territoire des ancêtres des Vietnamiens (Kiao-tche (Giao Chỉ) et Kieou-tchen (Cửu Chân)) était confiné dans le Tonkin actuel, ce qui les gêna d’accepter sans explication ni justification l’étendue territoriale de la dynastie des Hồng Bàng jusqu’au lac Dongting. Ils ne virent pas dans la narration de ce mythe la volonté des ancêtres des Vietnamiens de montrer leur origine, d’afficher leur appartenance au groupe Bai Yue et leur résistance inébranlable face aux conquérants redoutables qu’étaient les Chinois.

en vietnamien ou arbalète en français). Ils ont démontré la forte probabilité de la présence de la langue austro-asiatique dans la Chine du Sud et ont conclu qu’il y avait eu un contact entre la langue chinoise et la langue austro-asiatique dans le territoire de l’ancien royaume de Chu entre 1000 et 500 ans avant J.C. Cet argument géographique n’était jamais pris en compte sérieusement dans le passé par certains historiens vietnamiens car pour eux, cette dynastie relevait plutôt de la période mythique. De plus, d’après les sources chinoises, le territoire des ancêtres des Vietnamiens (Kiao-tche (Giao Chỉ) et Kieou-tchen (Cửu Chân)) était confiné dans le Tonkin actuel, ce qui les gêna d’accepter sans explication ni justification l’étendue territoriale de la dynastie des Hồng Bàng jusqu’au lac Dongting. Ils ne virent pas dans la narration de ce mythe la volonté des ancêtres des Vietnamiens de montrer leur origine, d’afficher leur appartenance au groupe Bai Yue et leur résistance inébranlable face aux conquérants redoutables qu’étaient les Chinois.

Dans les annales chinoises, on a rapporté qu’à la période des Printemps et Automnes (Xuân Thu), le roi Gou Jian(Câu Tiễn) des Yue (Wu Yue) s’intéressa à l’alliance qu’il aimerait contracter avec le royaume Văn Lang dans le but de maintenir la suprématie sur les autres principautés puissantes de la région. Il est probable que ce royaume de Văn Lang devait être un pays limitrophe de celui des Yuê de Gou Jian. Celui-ci ne trouva aucun intérêt de contracter cette alliance si ce royaume Văn Lang se trouvait confiné géographiquement dans le Vietnam d’aujourd’hui. La découverte récente de l’épée du roi Goujian de Yue (règne de 496-465 avant J.C) dans la tombe no 1 de Wanshan (Jianling) (Hubei) permet de mieux cerner les contours du royaume de Văn Lang. Il serait situé probablement dans la région de Qui Châu (ou GuiZhou). Mais Henri Masporo a contesté cette hypothèse dans son ouvrage intitulé « Le royaume de Văn Lang » (BEFEO, t XVIII, fac 3 ).

Il a attribué aux historiens vietnamiens l’erreur de confondre le royaume de Văn Lang avec celui de Ye Lang (ou Dạ Lang en vietnamien ) dont le nom aurait été mal transmis par les historiens chinois à leurs collègues vietnamiens à l’époque des Tang (nhà Đường). Ce n’est pas tout à fait exact car dans les légendes vietnamiennes, en particulier dans celle de « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương (ou le Seigneur céleste du village Phù Ðổng) on s’aperçoit que le royaume de Văn Lang était en conflit armé avec la dynastie des Yin-Shang (Ân-Thương) à l’époque du roi Hùng VI et qu’il était plus vaste que le royaume de Ye Lang trouvé à l’époque de l’unification de la Chine par Qin Shi Huang Di.

Dans les Annales du Vietnam, on a parlé de la longue période de règne des rois Hùng (de 2879 jusqu’à 258 avant J.C.). Les découvertes des objets en bronze à Ningxiang (Hu Nan) dans les années 1960 ont permis de ne mettre plus en doute l’existence des foyers de civilisation contemporains des Shang ignorés par les textes dans la Chine du Sud. C’est le cas de la culture de Sanxingdui (Sichuan) (Di chỉ Tam Tinh Đôi ) par exemple. Le vase à vin en bronze décoré de faces anthropomorphes témoigne évidemment du contact établi par les Shang avec les peuples de type mélanésien car on trouve sur ces faces des visages humains ronds avec un nez épaté. Le moulage de ce bronze employé dans la fabrication de ce vase nécessite l’incorporation de l’étain que le Nord de la Chine ne posséda pas à cette époque.

Dans les Annales du Vietnam, on a parlé de la longue période de règne des rois Hùng (de 2879 jusqu’à 258 avant J.C.). Les découvertes des objets en bronze à Ningxiang (Hu Nan) dans les années 1960 ont permis de ne mettre plus en doute l’existence des foyers de civilisation contemporains des Shang ignorés par les textes dans la Chine du Sud. C’est le cas de la culture de Sanxingdui (Sichuan) (Di chỉ Tam Tinh Đôi ) par exemple. Le vase à vin en bronze décoré de faces anthropomorphes témoigne évidemment du contact établi par les Shang avec les peuples de type mélanésien car on trouve sur ces faces des visages humains ronds avec un nez épaté. Le moulage de ce bronze employé dans la fabrication de ce vase nécessite l’incorporation de l’étain que le Nord de la Chine ne posséda pas à cette époque.

Y aurait-t-il un contact réel, un conflit armé entre les Shang et le royaume de Văn Lang si on se tenait à la légende du seigneur céleste de Phù Ðổng? Pourrait-ton accorder la véracité à un fait rapporté par une légende vietnamienne? Beaucoup d’historiens occidentaux ont perçu toujours la période de la civilisation dongsonienne comme le début de la formation de la nation vietnamienne (500-700 avant J.C.). C’est aussi l’avis partagé et trouvé dans l’ouvrage historique anonyme « Việt Sử Lược« .

Sous le règne du roi Zhuang Wang (Trang Vương) des Zhou ( 696-691 avant J.C.), il y avait dans le district Gia Ninh, un personnage étrange réussissant à dominer toutes les tribus avec ses magies, prenant pour titre le nom Hùng Vương et établissant sa capitale à Phong Châu. Avec la filiation héréditaire, cela a permis à sa lignée de maintenir le pouvoir avec 18 rois, tous portant le nom Hùng.

Par contre, dans d’autres ouvrages historiques vietnamiens, on accorda une longue période de règne à la dynastie des Hồng Bàng (de 2879 jusqu’à 258 avant J.C.) avec 2622 ans. Il nous parait inconcevable si on se tient au chiffre 18, le nombre de rois durant cette période car cela veut dire que chaque roi Hùng Vương régna en moyenne 150 ans. On ne peut trouver qu’une réponse satisfaisante si on se tient à l’hypothèse établie par Trần Huy Bá dans son exposé publié dans le journal Nguồn Sáng no 23 lors la journée de commémoration des rois Hùng Vương (Ngày giỗ Tổ Hùng Vương) ( 1998 ). Pour lui, il y a une fausse interprétation sur le mot đời trouvé dans la phrase « 18 đời Hùng Vương ». Le mot « Ðời » doit être remplacé par le mot Thời signifiant « période« . (7)

Avec cette hypothèse, il y a donc 18 périodes de règne dont chacune correspond à une branche pouvant être composée d’un ou de plusieurs rois dans l’arbre généalogique de la dynastie des Hồng Bàng. Cette argumentation est renforcée par le fait que le roi Hùng Vương était élu pour son courage et pour ses mérites si on se réfère à la tradition vietnamienne de choisir des hommes de valeur pour la fonction suprême. Cela a été rapporté dans la célèbre légende du gâteau de riz gluant (Bánh chưng bánh dầy) . On peut ainsi justifier le mot đời par le mot branche (ou chi ).

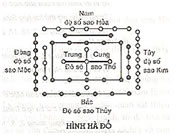

On est amené à donner une explication plus cohérente pour le chiffre 2622 avec 18 branches suivantes trouvées dans l’ouvrage « Văn hoá tâm linh – đất tổ Hùng Vương » de l’auteur Hồng Tử Uyên:

| Chi Càn |

Kinh Dương Vương húy Lộc Túc |

| Chi Khảm |

Lạc Long Quân húy Sùng Lãm |

| Chi Cấn |

Hùng Quốc Vương húy Hùng Lân |

| Chi Chấn |

Hùng Hoa Vương húy Bửu Lang |

| Chi Tốn |

Hùng Hy Vương húy Bảo Lang |

| Chi Ly |

Hùng Hồn Vương húy Long Tiên Lang |

| Chi Khôn |

Hùng Chiêu Vương húy Quốc Lang |

| Chi Ðoài |

Hùng Vĩ Vương húy Vân Lang |

| Chi Giáp |

Hùng Ðịnh Vương húy Chân Nhân Lang |

| ………….. |

manquant dans le document historique … |

| Chi Bính |

Hùng Trinh Vương húy Hưng Ðức Lang |

| Chi Ðinh |

Hùng Vũ Vương húy Ðức Hiền Lang |

| Chi Mậu |

Hùng Việt Vương húy Tuấn Lang |

| Chi Kỷ |

Hùng Anh Vương húy Viên Lang |

| Chi Canh |

Hùng Triệu Vương húy Cảnh Chiêu Lang |

| Chi Tân |

Hùng Tạo Vương húy Ðức Quân Lang |

| Chi Nhâm |

Hùng Nghị Vương húy Bảo Quang Lang |

| Chi Qúy |

Hùng Duệ Vương |

Cela nous permet de retrouver aussi le fil de l’histoire dans le conflit armé du royaume de Văn Lang avec les Shang par le biais de la légende de « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương« . Si ce conflit avait lieu, il ne pourrait qu’être au début de la période de règne des Shang pour plusieurs raisons:

1) Aucun document historique chinois ou vietnamien ne parla des relations commerciales entre le royaume de Văn Lang et les Shang. Par contre, on nota le contact établi plus tard entre la dynastie des Zhou et le roi Hùng Vương . Un faisan argenté (chim trĩ trắng) avait été offert même par ce dernier au roi des Zhou selon l’ouvrage Linh Nam Chích Quái.

2) La dynastie des Shang ne régna que de 1766 a 1122 avant J.C. Il y aurait approximativement un décalage de 300 ans si on tentait de faire la moyenne arithmétique de 18 périodes de règne des rois Hùng: ( 2622 / 18 ) et de la multiplier par 12 pour donner approximativement une date à la fin de règne de la sixième branche Hùng vương ( Hùng Vương VI ) en lui ajoutant 258 l’année de l’annexion du royaume de Văn Lang par le roi An Dương vương. On serait tombé à peu près à l’année 2006, date de la fin de règne de la sixième branche Hùng Vương ( Hùng Vương VI ) . On peut en déduire que le conflit s’il y avait lieu, devrait être au début de l’avènement de la dynastie des Shang. Ce décalage n’est pas tout à fait injustifié car on a jusque là peu de précisions historiques au delà de l’époque de règne du roi Chu Lệ Vương (Zhou LiWang) ( 850 avant J.C. ).

On note une expédition militaire entreprise au bout de trois ans par le roi des Shang de nom Wuding (Vũ Ðịnh) dans le territoire du lac Ðộng Ðình Hồ contre le peuple nomade, les Gui alias « Démons« , ce qui a été rapporté dans l’ouvrage Yi King (Kinh Dịch ) traduit par Bùi Văn Nguyên (Khoa Học Xã Hội Hà Nội 1997) . Dans son exposé publié dans le journal Nguồn Sáng no 23, Trần Huy Bá a pensé plutôt au roi Woding (Ốc Ðinh) qui était l’un des premiers rois de la dynastie des Shang. Avec cette hypothèse, il n’y a plus de doute et d’équivoque car il y a une parfaite cohérence rapportée dans les annales chinoise et vietnamienne. On doit savoir qu’à l’époque du roi An Dương Vương, on avait l’habitude de désigner le pays Việt Thường sous le nom Xích Qủi. Le terme Xích 赤 est employé pour désigner la couleur rouge et faire allusion au Sud. Quant à Qủi, cela veut évoquer l’étoile Yugui Qui de couleur rouge, la plus splendide des 28 constellations organisées dans l’astronomie chinoise. Celle-ci arriva sous le ciel de la ville Kinh Châu (Jīngzhōu) des Yue au moment où le roi des Shang eut installé sa troupe. C’est aussi l’avis partagé par l’auteur vietnamien Vũ Quỳnh dans son ouvrage « Tân Ðính Linh Nam Chích Quái« :

Ở đây có bộ tộc Thi La Quỷ thời Hùng Vương thứ VI vào đánh nước ta nhân danh nhà Ân Thương.

C’est ici qu’à l’époque de règne de Hùng Vương VI, on trouva une tribu Thi La Quỷ qui a envahi notre pays au nom des Yin-Shan. Ce conflit pourrait expliquer la raison principale pour laquelle le royaume de Văn Lang n’a établi aucune relation commerciale avec les Shang. Les découvertes des objets en bronze à Ningxiang (Hu Nan) dans les années 1960 ont mis en évidence qu’il pourrait s’agir des butins ramenés lors de l’expédition dans le sud de la Chine car il n’y avait aucune explication à donner aux vases à vin en bronze décorés de faces anthropomorphes mélanésiennes.

3) Dans la légende vietnamienne « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương« , on nota la fuite et la dislocation de l’armée des Shang dans le district Vũ Ninh en même temps la disparition immédiate du héros céleste du village Phù Ðổng. On raconta aussi son apparition spontanée au moment de l’invasion des Shang sans aucune préparation à l’avance. Cela mit en évidence qu’il devrait être présent sur le terrain lors de l’invasion de ces derniers. Les territoires conquis par les Shang ne pouvaient pas être repris entièrement par les Lạc Việt car sinon on pourrait dire qu’ils étaient chassés du territoire Văn Lang dans la légende. Ce n’était pas tout à fait le cas car on constata qu’avec l’avènement des Zhou, on vit apparaître sur une ancienne partie du territoire de Văn Lang, des pays vassaux comme le pays des Yue de Goujian (Wu Yue)(Ngô Việt), le pays Chu (Sỡ) etc…

On ne saurait pas pour quelles raisons le royaume de Văn Lang serait réduit et confiné ainsi dans le nord du Việt-Nam d’aujourd’hui en jetant un coup d’œil sur les cartes géographiques trouvées à l’époque des Printemps et Automnes et de l’empereur Qin Shi Huang Di. Pourquoi Goujian, le roi des Yue, s’intéressa-t-il à l’alliance avec le royaume de Văn Lang si ce dernier se cantonnait dans le nord du Vietnam actuel? On pourrait donner au démembrement de ce royaume l’explication suivante:

Au moment de l’invasion des Yin-Shan, un certain nombre de tribus parmi les 15 tribus que comportait le peuple Lạc Việt, ont réussi à mettre en déroute l’armée des Shang et ont continué à afficher leur rattachement et leur loyauté au royaume de Văn Lang. Cela ne les empêcha pas de garder leur autonomie et de maintenir un développement assez élevé au niveau social et culturel. Cela pourrait donner une explication plus tard à l’apparition des foyers états indépendants bien situés sur la carte géographique de l’époque de Tsin (Qin Shi Huang Di) comme Dạ Lang (Ye Lang), Ðiền Việt (Dian) , Tây Âu (Si Ngeou) et au rétrécissement significatif du royaume de Van Lang à l’état actuel (dans le nord du Vietnam).

Il ne serait pas impossible que ce royaume réduit se restructura de manière identique à l’image du royaume de Văn Lang trouvé au début de sa création par le dernier roi Hùng Vương dans le but de rappeler à son peuple la grandeur de son royaume. Le roi garda ainsi les noms des 15 anciennes tribus et donna à son territoire réduit le nom Vũ Ninh dans le but de commémorer le succès éclatant remporté par le peuple Lạc Việt sous le règne de Hùng Vương VI. Việt Trì serait probablement la dernière capitale du royaume de Văn Lang. On note une part de réalité historique dans cette légende vietnamienne car on découvrit récemment en Chine l’utilisation du fer à l’époque des Shang. Ce fer pourrait être remplacé d’autre part par un autre métal comme le bronze sans perdre pour autant la signification réelle dans le contenu de la légende. Il y était employé uniquement pour refléter le courage et la bravoure qu’on aimait attribuer au héros céleste. S’il y était cité ainsi, cela ne mit plus en doute la découverte du fer et son utilisation très tôt dans le royaume de Văn Lang. Cela justifie aussi la cohérence apportée par cette légende au conflit qui a opposé le royaume de Văn Lang aux Shang.[Civilisation Văn Lang: 2ème partie]

Bibliographie:

(1) Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

(2) Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

(3)Jīngzhōu (Kinh Châu) : la capitale de vingt rois de Chu, au cours de la période des Printemps et Automnes (Xuân Thu) (-771 — ~-481)

(4) Yángzhōu (Dương Châu)

(5) Léonard Aurousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1.

(5) Edouard Chavannes :Mémoires historiques de Se-Ma Tsien de Chavannes, tome quatrième, page 170).

(5) Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin 1976 The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

(7) Nguyễn Vũ Tuấn Anh: Thời Hùng vương qua truyền thuyết và huyền thoại. Nhà xuất bản văn hóa Thông Tin 1999

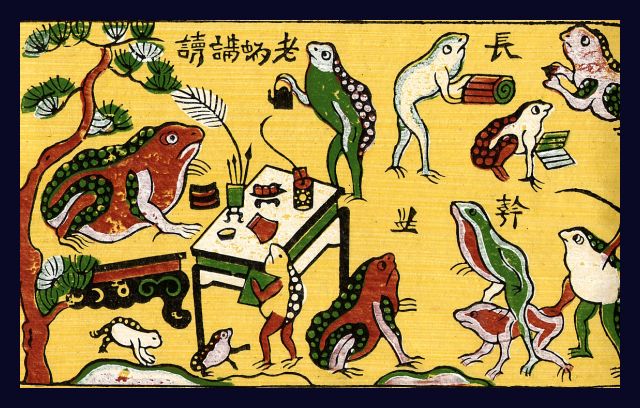

Guimet museum of Asian art (Paris)

Guimet museum of Asian art (Paris)![]()

![]()