Back to the past with the Cham people

En s’appuyant sur des documents historiques chinois et vietnamiens, les deux chercheurs français Gaston Maspéro et George Coedès ont essayé de reconstituer la chronologie chame. Malgré d’importantes lacunes, la mention des Chams a été évoquée à l’époque où les habitants de la province de Tượng Lâm (Rinan) s’étaient soulevés contre la domination chinoise en 192 après J.C. pour fonder un état indépendant dont le territoire s’étendait du Quảng Bình jusqu’au Phan Rang. Cet état était réparti en quatre zones: Amaravati (de Quảng Bình à Quảng Nam), Vijaya (de Quảng Ngãi à Phú Yên), Kauthara (Khánh Hoà) et Panduranga (Phan Rang). Deux clans, celui du Nord (ou le clan des Narikelavamsa) (clan Dừa en vietnamien) et celui du Sud ( ou le clan des Kramukavamsa ) (clan Cau en vietnamien) qui par moments guerroyèrent, prirent les rênes du pouvoir par alternance. En fonction de leurs offrandes retrouvées, (noix de coco au Nord et noix d’arec au Sud), ils étaient appelés comme les mangeurs de coco au Nord et ceux d’arec au Sud. Ce pays dont la capitale était sans doute à Trà Kiệu (près de Ðà Nẵng) fut connu durant six siècles sous le nom de Lin Yi (Lâm Ấp) puis à partir de 758 sous celui de Houan Xang (Hoàn Vương). Le nom de Champa (Chiêm Thành ) provenant de la transcription sino-vietnamienne Champapura (cité des Chàms) fut cité pour la première fois en 875.

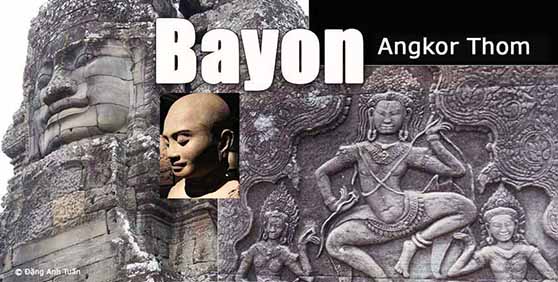

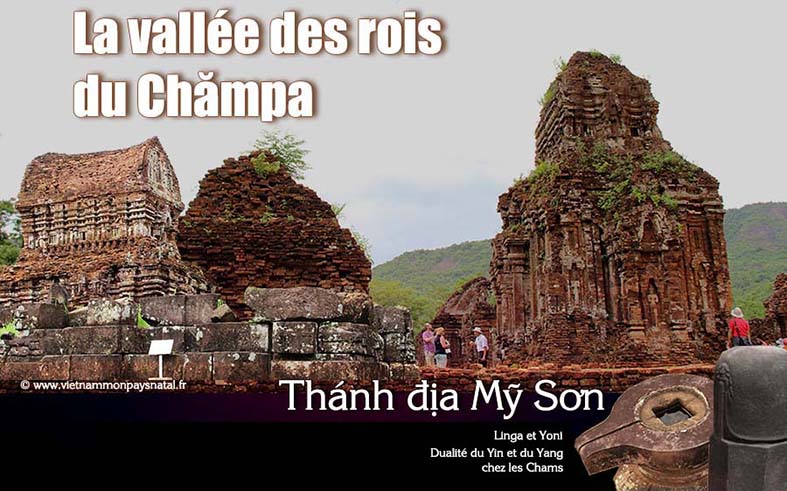

C’était avec ce nom que ce royaume était mentionné maintes fois dans les conflits avec le Vietnam jusqu’à son annexion sous la dynastie des Lê avec le roi Lê Thánh Tôn. Au début de son existence, ce royaume connut une période de prospérité. On vit la construction d’un grand nombre de temples et de sanctuaires dont le premier était celui du site de Mỹ Sơn (Belle Montagne) dédié au culte du linga du dieu roi Civa Bhadresvara par le grand souverain Bhadravarman, c’est ce qu’on a découvert dans les inscriptions écrites en sanskrit. Les fouilles récentes à Mỹ Sơn ont apporté la preuve que Mỹ Sơn n’était pas seulement un lieu de culte mais aussi la nécropole des rois Chàm après l’incinération. On dénombra deux grands ports où le commerce était très florissant: Ðại Chiêm dans la région de Hội An (Faifo) et Thị Nại (Bình Ðịnh)(Sri Bonei).

Du IV au Vème siècle, ce royaume fut en conflit acharné avec les Chinois qui avaient annexé le Vietnam au nord du Col de Ðèo Ngang. Sa capitale Trà Kiệu connue sous le nom de Simhapura (cité du Lion) et située à 50km au sud-ouest de Ðà Nẵng, fut mise à sac vers 446. Le général chinois Tan Hezhi (Ðàn Hoà Chi) ramena lors de cette expédition des statues en or pour une valeur totale de cent mille taëls d’or (environ 3600 kg).

La prospérité de cette capitale ne fut plus mise en doute à la suite des découvertes d’un grand nombre d’objets en or finement travaillés pendant les années 80. La description détaillée de cette ville fut déjà mentionnée dans un ouvrage d’histoire chinois Shu Jing Zhu (Thủy Kinh Chú) du VIIème siècle après J. C. Elle a été confirmée par les fouilles en 1927-1928 sous la direction de l’archéologue français J. Y. Claèys de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient.

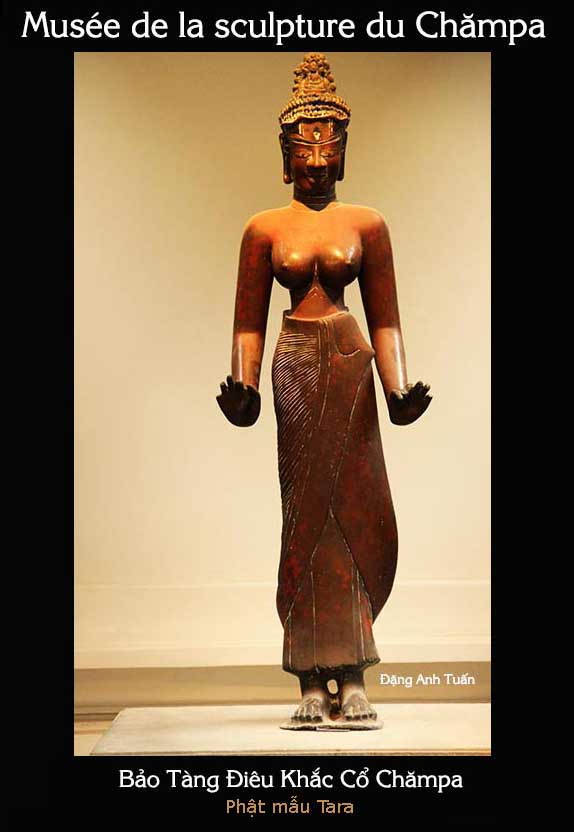

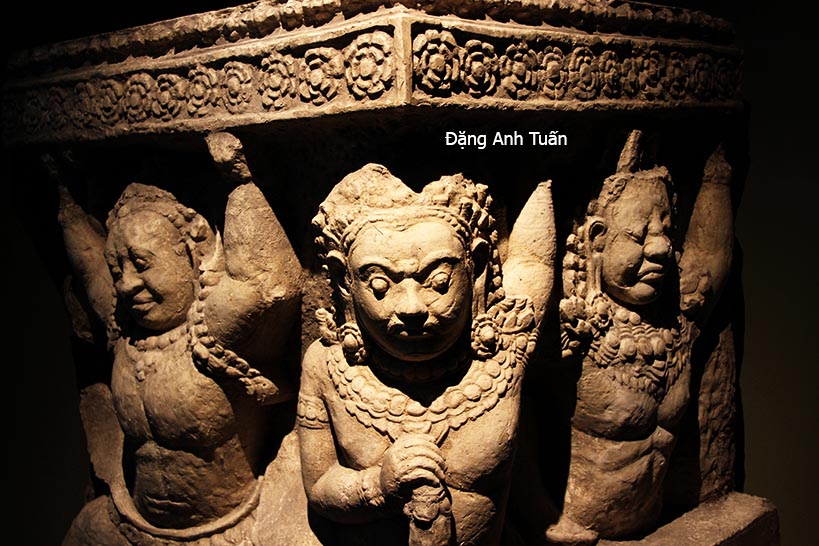

Du VIème au VIIIème siècle, ce royaume retrouva un essor économique et artistique par le biais des relations très développées avec l’Inde et le Tchenla (Chân Lạp) au Sud. On nota ainsi une introduction importante des objets étrangers dans l’art du Chămpa. Au VIIIème siècle, les Chams furent attaqués sans cesse par les Javanais. Ces derniers détruisirent en 774 le temple de Pô Nagar (Nha Trang) construit en bois par un roi légendaire Vichitrasagara.

Ce sanctuaire fut reconstruit à nouveau cette fois en brique par le roi Satyavarman Içvaraloka en 784. D’après ce qu’on a recueilli dans les inscriptions chames, avant le VIIème siècle, les temples et les tours étaient en bois mais ils ont été incendiés au cours des guerres. C’est seulement au VIIème siècle qu’on vit apparaître les temples et les tours en briques et en grès.

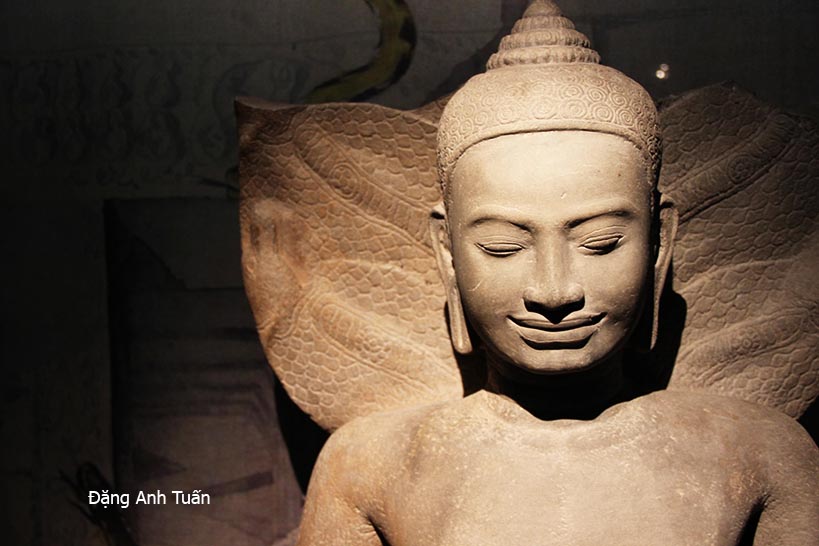

Dès sa montée sur le trône en 854, Indravarman II changea le nom de la capitale de Simhapura dans la région de Trà Kiệu en Indrapura (cité du Dieu de la foudre). Il fit édifier une cité sainte du bouddhisme à Ðồng Dương à 20km au sud de Trà Kiệu et rétablit de bonnes relations avec la Chine.

Au début du Xème siècle, sous le règne du roi Indravarman III, le royaume du Champa commença à tisser des relations étroites avec Java. Rien n’est étonnant de voir l’art cham en contact avec l’art javanais pour tout le siècle.

Par contre, il était en conflit sempiternel au nord avec un nouveau pays, le Ðại Cồ Việt qui vint d’être libéré de la domination chinoise à la fin du Xème siècle et au Sud avec les Khmers. Ceux-ci n’hésitèrent pas à saccager le sanctuaire Po Nagar de Nha Trang vers 950 et dérobèrent la statue d’or qui y avait été installée en 918 par le roi Indravarman II. Les Chams engagèrent des guerres sans merci contre les Khmers durant plus d’un siècle (1112-1220). On nota aussi leurs premiers accrochages sérieux avec le Ðại Cồ Việt en 979. Leur capitale fut pillée en 982 par ce dernier. (l’expédition du grand roi vietnamien Lê Ðại Hành). Face à la pression de celui-ci, le roi Yang Sra Vijaya dut transférer sa capitale dans la région de Vijaya (Bỉnh Ðịnh). Cette nouvelle capitale allait durer jusqu’en 1471 avant d’être transférée à la région de Panduranga (Ninh Thuận).

À cause des dissensions internes et de la guerre de cent ans avec les Khmers, les Chams ne réussirent pas à stopper au fil des siècles la marche du Sud entamée par les Vietnamiens. Ils durent un dernier sursaut à Binasuor(*) (Chế Bồng Nga) qui battit les Vietnamiens à maintes reprises en pillant leur capitale Thăng Long en 1371 et en 1377 et en faisant fuir leur roi Trần Nghệ Tôn et son premier ministre Hồ Qúi Ly. A cause de la trahison de l’un de ses proches, les Vietnamiens réussirent à tuer Binasuor. Cela mit fin à la suprématie des Chams. Ceux-ci devaient céder le terrain aux conquérants vietnamiens et étaient refoulés un peu plus chaque jour dans le Sud. Par la politique d’assimilation, ils étaient obligés d’être disséminés un peu partout dans le centre du Vietnam et dans l’ouest du Sud Vietnam, au Cambodge et en Malaisie.

(*) Certains historiens contestent le nom Binasuor donné à Chế Bồng Nga. (nom mentionné par les Vietnamiens dans leurs documents historiques).

Trở về quá khứ với dân tộc Chàm

Căn cứ vào các tài liệu lịch sử Trung Quốc và Việt Nam, hai nhà nghiên cứu người Pháp Gaston Maspéro và George Coedès đã cố gắng dựng lại niên đại của người dân chàm. Mặc dù có những khoảng trống quan trọng, người ta vẫn thường nhắc đến người dân Chàm vào thời điểm mà cư dân của tỉnh Tượng Lâm (Rinan) vùng lên chống lại sự đô hộ của Trung Quốc vào năm 192 sau Công nguyên để thành lập một quốc gia độc lập có lãnh thổ trải dài từ Quảng Bình đến Phan Rang. Quốc gia này được chia ra thành bốn vùng: Amaravati (từ Quảng Bình đến Quảng Nam), Vijaya (từ Quảng Ngãi đến Phú Yên), Kauthara (Khánh Hoà) và Panduranga (Phan Rang). Hai thị tộc, một ở miền Bắc (hay tộc Narikelavamsa) (tộc Dừa trong tiếng Việt) và một ở miền Nam (hay tộc Kramukavamsa) (tộc Cau trong tiếng Việt) có những lúc giao chiến khốc liệt và luân phiên nhau nắm quyền hành.

Tuỳ theo các lễ vật cúng được tìm thấy (các trái dừa ở miền Bắc và các quả cau ở miền Nam), họ được gọi là những người ăn dừa ở miền Bắc và những người ăn cau ở miền Nam. Không còn sự nghi ngờ gì nào nữa, đất nước này có một kinh đô ở Trà Kiệu (gần Ðà Nẵng), được biết đến trong sáu thế kỷ liên tục với tên Lâm Ấp và sau đó từ năm 758 được mang tên là Hoàn Vương. Còn tên Chiêm Thành, nó xuất phát từ phiên âm Hán Việt của từ Champapura (thành phố của người dân Chàm) được nhắc đến lần đầu tiên vào năm 875. Chính nhờ cái tên gọi này, vương quốc mới được nói đến nhiều lần trong các cuộc xung đột với Việt Nam cho đến sự sáp nhập dưới triều đại nhà Lê với vua Lê Thánh Tôn.

Lúc ban đầu vương quốc này đã trải qua một thời kỳ cực thịnh. Được tìm thấy có rất nhiều ngôi đền thờ mà công trình đầu tiên là thánh địa Mỹ Sơn ( hay Núi Đẹp) dành để thờ linga của thần Civa Bhadresvara bởi vua vĩ đại Bhadravarma. Đây là những gì đã được phát hiện trên các bia ký viết bằng tiếng Phạn. Những cuộc khai quật gần đây ở Mỹ Sơn đã cung cấp bằng chứng cho thấy rằng Mỹ Sơn không chỉ là nơi thờ tự mà còn là tử địa của các vị vua Chàm sau khi hỏa táng. Có hai thương cảng lớn mà mâu dịch rất được thịnh vượng: Ðại Chiêm ở vùng Hội An (Faifo) và Thị Nại (Bình Ðịnh) (Sri Bonei).

Từ thế kỷ 4 đến thế kỷ 5, vương quốc này có cuộc xung đột kịch liệt với Trung Quốc khi nước nầy đã thôn tính Việt Nam ở phía bắc Đèo Ngang. Kinh đô Trà Kiệu được biết đến dưới tên Simhapura (thành phố Sư tử) và nằm cách Ðà Nẵng 50 cây số về phía tây nam, bị cướp phá vào khoảng năm 446. Tướng quân Trung Hoa tên là Ðàn Hoà Chi đã mang về nước những tượng vàng trong cuộc viễn chinh này trị giá tổng công là một trăm nghìn lượng vàng (tương đương 3600 kí lô). Sự thịnh vượng của thủ đô này không còn là nghi vấn nữa sau khi phát hiện ra một số lượng lớn các đồ vật bằng vàng được chế tạo một cách tinh xảo trong những năm 1980. Sự mô tả chi tiết về thành phố này đã được đề cập trong một cuốn sách lịch sử Trung Quốc Thủy Kính Chủ (Shu Jing Zhu) từ thế kỷ thứ 7 sau Công nguyên và đã được xác nhận bởi các cuộc khai quật vào những năm 1927-1928 dưới sự chỉ đạo của nhà khảo cổ học người Pháp J.Y. Claèys của Trường Viễn Đông Pháp.

Từ thế kỷ 6 đến thế kỷ 8, vương quốc này có được sự tăng trưởng kinh tế và nghệ thuật thông qua các quan hệ phát triển với Ấn Độ và Chân Lạp ở phía Nam. Do đó, có một sự gia nhập quan trọng của các vật thể ngoại lai trong nghệ thuật Chămpa. Vào thế kỷ thứ 8, người Chăm liên tục bị người Chà Và (Java) tấn công. Sau khi bị phá hủy vào năm 774, đền thờ Pô Nagar ở Nha Trang được xây dựng lại bằng gỗ bởi một vị vua huyền thoại Vichitrasagara.

Thánh địa này được vua Satyavarman Içvaraloka xây dựng lại lần này bằng gạch vào năm 784. Theo những gì chúng ta tìm thấy trên các bia ký của người Chăm, trước thế kỷ thứ 7, các ngôi đền và các tháp đều được làm bằng gỗ nhưng chúng đã bị đốt cháy trong các cuộc chiến tranh. Chỉ đến thế kỷ thứ 7, các ngôi đền và các tháp bằng gạch và đá sa thạch mới thấy xuất hiện.

Khi lên ngôi vào năm 854, Indravarman II đã đổi tên thủ đô Simhapura ở vùng Trà Kiệu thành Indrapura (Thành phố của Thần Sét). Ông đã xây dựng một thánh địa Phật giáo tại Ðồng Dương, cách Trà Kiệu 20 c ây số về phía nam và thiết lập lại mối quan hệ tốt đẹp với Trung Quốc.

Vào đầu thế kỷ thứ 10, dưới triều đại của vua Indravarman III, vương quốc Champa bắt đầu thiết lập quan hệ thân thiết với Java. Không có gì ngạc nhiên khi thấy nghệ thuật Chăm tiếp cận với nghệ thuật Java trong suốt cả thế kỷ.

Mặt khác, ở phía bắc có một cuộc xung đột triền miên với một quốc gia mới, nước Ðại Cồ Việt vừa được giải phóng ra khỏi ách thống trị của Trung Quốc vào cuối thế kỷ thứ 10 và ở phía nam với những người Khơ Me. Những người nầy không ngần ngại cướp phá đền thờ Po Nagar ở Nha Trang vào khoảng năm 950 và lấy trộm bức tượng vàng được đặt ở đây vào năm 918 bởi vua Indravarman II. Người Chăm đã tiến hành các cuộc chiến tranh tàn khốc chống lại người Khơ Me có hơn một thế kỷ (1112-1220). Chúng ta cũng ghi nhận cuộc đụng độ nghiêm trọng đầu tiên của họ với Đại Cồ Việt vào năm 979. Kinh đô của họ bị cướp phá vào năm 982 bởi người dân nước nầy (cuộc viễn chinh của vua vĩ đại Lê Ðại Hành). Trước sức ép của người dân Việt, vua Yang Sra Vijaya phải dời đô về vùng Vijaya (Bình Ðịnh). Thủ đô mới này được tồn tại đến năm 1471 trước khi được chuyển đến vùng Ninh Thuận (Panduranga).

Vì những bất đồng ở trong nội bộ và cuộc chiến tranh hơn một trăm năm với người Khơ Me, người Chăm đã không thành công trong việc ngăn chặn được Nam Tiến của người dân Việt qua nhiều thế kỷ. Họ có được một nổ lực lần cuối với Chế Bồng Nga (*), người anh hùng Chàm đã đánh bại người dân Việt nhiều lần bằng cách cướp bóc kinh đô Thăng Long vào năm 1371 và năm 1377 và làm vua Trần Nghệ Tôn và tể tướng Hồ Qúi Ly phải bỏ trốn kinh thành. Do sự phản bội của một trong những người thân tín của mình, người Việt đã tìm cách giết được Chế Bồng Nga. Việc này kết thúc sự ưu thế của người dân Chàm. Từ đó những người này phải nhường bước trước những người viễn chinh Việt và bị đẩy lùi mỗi ngày một ít ở miền Nam. Bằng chính sách đồng hóa, họ buộc lòng phải ở rải rác từ đây khắp cả miền trung Việt Nam, miền tây Nam Bộ, Cao Miên và Mã Lai.

(*) Một số sử gia tranh cãi về cái tên Binasuor gán cho Chế Bồng Nga. (Tên nầy được người Việt Nam nhắc đến trong các tài liệu lịch sử của họ).

Back to the past with the Cham people

Relying on Chinese and Vietnamese historical documents, the two French researchers Gaston Maspéro and George Coedès tried to reconstruct the Cham chronology. Despite significant gaps, the mention of the Chams was made at the time when the inhabitants of the province of Tượng Lâm (Rinan) rose up against Chinese domination in 192 AD to found an independent state whose territory extended from Quảng Bình to Phan Rang. This state was divided into four zones: Amaravati (from Quảng Bình to Quảng Nam), Vijaya (from Quảng Ngãi to Phú Yên), Kauthara (Khánh Hòa), and Panduranga (Phan Rang). Two clans, the Northern clan (or the Narikelavamsa clan) (Dừa clan in Vietnamese) and the Southern clan (or the Kramukavamsa clan) (Cau clan in Vietnamese), who at times waged war, took turns holding power. Based on their offerings found (coconuts in the North and areca nuts in the South), they were called the coconut eaters in the North and the areca eaters in the South. This country, whose capital was probably at Trà Kiệu (near Ðà Nẵng), was known for six centuries under the name Lin Yi (Lâm Ấp) and then from 758 under that of Houan Xang (Hoàn Vương). The name Champa (Chiêm Thành), coming from the Sino-Vietnamese transcription Champapura (city of the Chams), was mentioned for the first time in 875.

It was with this name that this kingdom was mentioned many times in conflicts with Vietnam until its annexation under the Lê dynasty with King Lê Thánh Tôn. At the beginning of its existence, this kingdom experienced a period of prosperity. A large number of temples and shrines were built, the first being the site of Mỹ Sơn (Beautiful Mountain) dedicated to the worship of the linga of the god-king Shiva Bhadresvara by the great sovereign Bhadravarman, as discovered in inscriptions written in Sanskrit. Recent excavations at Mỹ Sơn have provided evidence that Mỹ Sơn was not only a place of worship but also the necropolis of the Champa kings after cremation. Two major ports were counted where trade was very flourishing: Ðại Chiêm in the Hội An (Faifo) region and Thị Nại (Bình Ðịnh) (Sri Bonei).

From the 4th to the 5th century, this kingdom was in fierce conflict with the Chinese who had annexed Vietnam north of the Ðèo Ngang Pass. Its capital Trà Kiệu, known as Simhapura (Lion City) and located 50 km southwest of Ðà Nẵng, was sacked around 446. The Chinese general Tan Hezhi (Ðàn Hoà Chi) brought back during this expedition gold statues worth a total of one hundred thousand taels of gold (approximately 3600 kg).

From the 6th to the 8th century, this kingdom experienced an economic and artistic resurgence through highly developed relations with India and Chenla (Chân Lạp) to the south. There was thus a significant introduction of foreign objects into Cham art. In the 8th century, the Chams were constantly attacked by the Javanese. In 774, the latter destroyed the Pô Nagar temple (Nha Trang), which had been built of wood by the legendary king Vichitrasagara.

This sanctuary was rebuilt, this time in brick, by King Satyavarman Içvaraloka in 784. According to what has been gathered from Cham inscriptions, before the 7th century, temples and towers were made of wood but were burned down during wars. It was only in the 7th century that temples and towers made of brick and sandstone appeared.

Upon ascending the throne in 854, Indravarman II changed the name of the capital from Simhapura in the Trà Kiệu region to Indrapura (City of the God of Thunder). He built a sacred Buddhist city at Ðồng Dương, 20 km south of Trà Kiệu, and restored good relations with China.

At the beginning of the 10th century, under the reign of King Indravarman III, the kingdom of Champa began to forge close relations with Java. It is not surprising to see Cham art in contact with Javanese art throughout the century.

However, it was in perpetual conflict in the north with a new country, Đại Cồ Việt, which had just been freed from Chinese domination at the end of the 10th century, and in the south with the Khmers. The latter did not hesitate to sack the Po Nagar sanctuary in Nha Trang around 950 and stole the golden statue that had been installed there in 918 by King Indravarman II. The Chams waged merciless wars against the Khmers for more than a century (1112-1220). Their first serious clashes with Đại Cồ Việt were also noted in 979. Their capital was pillaged in 982 by the latter (the expedition of the great Vietnamese king Lê Đại Hành). Facing pressure from him, King Yang Sra Vijaya had to transfer his capital to the Vijaya region (Bình Định). This new capital lasted until 1471 before being moved to the Panduranga region (Ninh Thuận).

Because of internal dissensions and the Hundred Years’ War with the Khmers, the Chams were unable to stop, over the centuries, the southward advance initiated by the Vietnamese. They made a last stand under Binasuor(*) (Chế Bồng Nga), who defeated the Vietnamese many times by pillaging their capital Thăng Long in 1371 and 1377 and forcing their king Trần Nghệ Tôn and his prime minister Hồ Qúi Ly to flee. Because of the betrayal of one of his close associates, the Vietnamese managed to kill Binasuor. This ended the supremacy of the Chams. They had to yield ground to the Vietnamese conquerors and were pushed back a little more each day to the south. Through assimilation policies, they were forced to be scattered throughout central Vietnam, the western part of southern Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia.

(*) Some historians dispute the name Binasuor given to Chế Bồng Nga. (name mentioned by the Vietnamese in their historical documents).