Thời kỳ Hồng Bàng

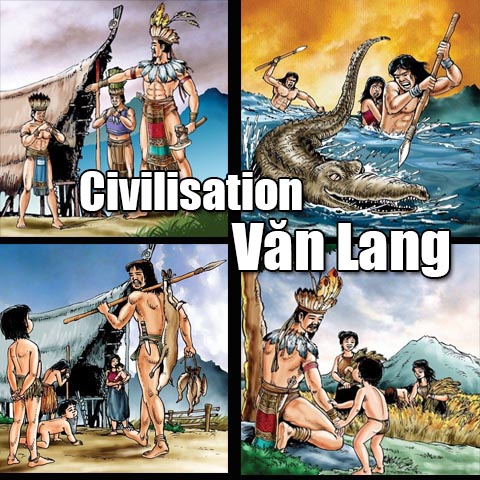

Văn Lang civilization

The Vietnamese are accustomed to saying: one remembers the source from which one drinks the water (Uống nước nhớ nguồn). It is therefore not surprising to see them continue to celebrate in grand pomp on the 10th day of the third lunar month of each year, the commemorative day of the Hùng kings of the Hồng Bàng dynasty, the founding fathers of the Vietnamese nation. Until today, no archaeological vestige is found to confirm the existence of this dynasty except for the ruins of the citadel Cỗ Loa (Old snail city) dating from the period of the An Dương Vương‘s reign and the temple built in honor of these Hùng kings at Phong Châu in the province of Phú Thọ.

Many clues do not invalidate this existence if one refers to the legends reported of this mythical time and the Annals of Vietnam and China. The Chinese domination (IIIrd century before J.C. – 939 after J.C.) is not foreign to the greatest influence on the development of the Vietnamese civilization. All that belongs to the Vietnamese became Chinese and vice versa during this period. One notes it is a policy of assimilation deliberately wanted by the Chinese. That does not let the Vietnamese the possibility for maintaining their culture inherited from an old civilization of 5000 years and called « Văn Lang civilization » without resorting to the oral traditions (popular proverbs, poems or legends).

Two verses found in the following popular song (ca dao):

Trăm năm bia đá thì mòn

Ngàn năm bia miệng vẫn còn trơ trơ

The stele of stone erodes after a hundred years

The words of people continue to remain in force after a thousand years

testify to the practice carried out knowingly by the Vietnamese with the goal of preserving what they inherited from the Văn Lang civilization.

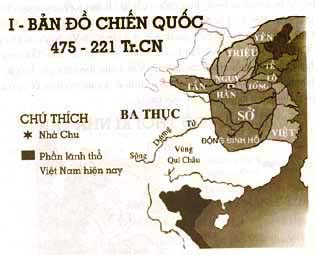

This one bears the name of a kingdom which was bordered at that time by the East sea, to the west by the Shu Ba kingdom (Ba Thục)(Tứ Xuyên or Szechuan in English), to the north by the territory of the lake Ðông Ðình (Hu Nan) (Hồ Nam) and to the south by the kingdom of Chămpa (Champa). This state was located in the Yang Tse river (Dương Tữ giang) Basin region and was placed under the authority of a king Hùng. This one had been elected for his courage and his values. He had divided his kingdom into districts entrusted to his brothers known under the name « Lạc hầu » (marquis). His male children have the title of Quang Lang and his daughters that of Mỵ nương. His people was known under the name « Lạc Việt ». His men had a custome of tattooing their body. Being often revealed in the Chinese annals, this « barbarian » practice was intended to protect men from the attacks of water dragons (con thuồng luồng) if one believes the Vietnamese texts. It is perhaps the reason why the Chinese often designated them under the name Qủi (demons). Loincloth and chignon constituted the usual costume of these people to which were added bronze ornaments. The Lac Viet lacquered their teeth in black, chewed betel nuts and crushed rice with their hand. Being farmers, they practiced the cultivation of rice in flooded field. They lived in plains and coastal areas while in the mountainous areas of Việt Bắc and on the part of the territory of the Kuang Si province, took refuge the Tây Âu, the ancestors of the ethnic groups Tày, Nùng and Choang.

Towards the end of the third century before our era, the leader of Tây Âu tribes defeated the last king Hùng and succeeded in reunifying under his banner the territories of Tây Âu and Lac Việt to form the Âu Lạc kingdom, in the year 258 before our era. He took as the reign name, An Dương Vương and transferred his capital to Cỗ Loa located just over 20 kilometers from Hànội.

Is the kingdom of Văn Lang a pure fabrication supplied by the Vietnamese with an aim of maintaining a myth or a kingdom really existing and disappeared in the swirls of history?

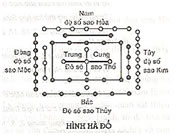

Geographic map of Văn Lang kingdom

According to the Vietnamese myth, the land of the Proto-Vietnamese was delimited in the north, at the time of Hùng kings (first vietnamese dynasty 2879 before J.C.) by the Dongting lake (Động Đình Hồ) located in the land of the Chu kingdom (Sỡ Quốc in Vietnamese). A part of their territory returned to this latter during the Warring States period (thời Chiến Quốc). Their descendants living in this part reattached probably became inhabitants of the Chu kingdom. There were a relationship, an intimate connection between in this kingdom and the Proto-Vietnamese. There is a hypothesis suggested and proposed recently by a Vietnamese writer Nguyên Nguyên (2). According to the latter, it is not rare that in the old writings, ideograms are replaced by other ideograms with the same phonetics. It is the case of the title Kinh Dương Vương whom had taken the father of the ancestor of the Vietnamese, Lộc Tục. By writing it in this way in Chinese ![]() , we see appearing easily the names of two cities Kinh Châu (Jingzhou) (3) and Dương Châu (Yángzhou) (4) where lived respectively the Yue ethnic groups of Thai branch and Lạc branch. There was the expression of a desire employed by the narrator for evoking intelligently the installation and fusion of yue ethnic groups of Thai branch and Lạc branch coming from these cities during the conquests of the Chu kingdom. On the other hand, the ideogram 陽 (Thái dương) is translated as light or solemn. It is employed with the aim of avoiding its use as surname. By using this word, it allows to translate Kinh Dương Vương

, we see appearing easily the names of two cities Kinh Châu (Jingzhou) (3) and Dương Châu (Yángzhou) (4) where lived respectively the Yue ethnic groups of Thai branch and Lạc branch. There was the expression of a desire employed by the narrator for evoking intelligently the installation and fusion of yue ethnic groups of Thai branch and Lạc branch coming from these cities during the conquests of the Chu kingdom. On the other hand, the ideogram 陽 (Thái dương) is translated as light or solemn. It is employed with the aim of avoiding its use as surname. By using this word, it allows to translate Kinh Dương Vương ![]() into solemn king Kinh. But there is also a synonymic word Kinh

into solemn king Kinh. But there is also a synonymic word Kinh ![]() of the word Lạc (

of the word Lạc (![]() ), nickname of the Vietnamese. In short, Kinh Dương Vương can be translated as solemn king Việt. Concerning the title whom took the Âu Việt king , the author does not question his explanation: it is the pacification of the country of the Yue ethnic group from the Lạc branch by a Yue son from the Thái branch. This can only strengthen the argument given by Edouard Chavannes and Léonard Aurousseau(5): the Proto-Vietnamese and the inhabitants of the Chu kingdom have had common ancestors. Moreover, there is a striking coincidence found in the clan name Mi (bear or gấu in Vietnamese) written in the Chu language, translated into Hùng (熊) (in Vietnamese) and beared by Chu kings and that of Vietnamese kings. By relying on Sseu-Ma Tsien historical memories translated by E. Chavannes (6), one knowns that the king of the Chu principality is from bararian hordes living in the South China (or Bai Yue): Hiong-K’iu (Hùng Cừ) says: I am a barbarian man and does not participe in titles and posthumous names granted by the Middle kingdom.

), nickname of the Vietnamese. In short, Kinh Dương Vương can be translated as solemn king Việt. Concerning the title whom took the Âu Việt king , the author does not question his explanation: it is the pacification of the country of the Yue ethnic group from the Lạc branch by a Yue son from the Thái branch. This can only strengthen the argument given by Edouard Chavannes and Léonard Aurousseau(5): the Proto-Vietnamese and the inhabitants of the Chu kingdom have had common ancestors. Moreover, there is a striking coincidence found in the clan name Mi (bear or gấu in Vietnamese) written in the Chu language, translated into Hùng (熊) (in Vietnamese) and beared by Chu kings and that of Vietnamese kings. By relying on Sseu-Ma Tsien historical memories translated by E. Chavannes (6), one knowns that the king of the Chu principality is from bararian hordes living in the South China (or Bai Yue): Hiong-K’iu (Hùng Cừ) says: I am a barbarian man and does not participe in titles and posthumous names granted by the Middle kingdom.

American linguists Mei Tsulin and Norman Jerry (7) identified a number of borrowed words in the Austro-Asiatic language and recognized them in Chinese writings during the Han period. There is the case of the Chinese word 囝 (giang in Vietnamese or river in French ) or nu (ná ![]() in Vietnamese or crossbow in English). They demonstrated the high likelihood of the Austro-Asiatic language presence in South China and concluded that there was a contact between the Chinese language and the Austro-Asiatic language in the territority of the former kingdom of Chu between 1000 and 500 years before J.C.

in Vietnamese or crossbow in English). They demonstrated the high likelihood of the Austro-Asiatic language presence in South China and concluded that there was a contact between the Chinese language and the Austro-Asiatic language in the territority of the former kingdom of Chu between 1000 and 500 years before J.C.

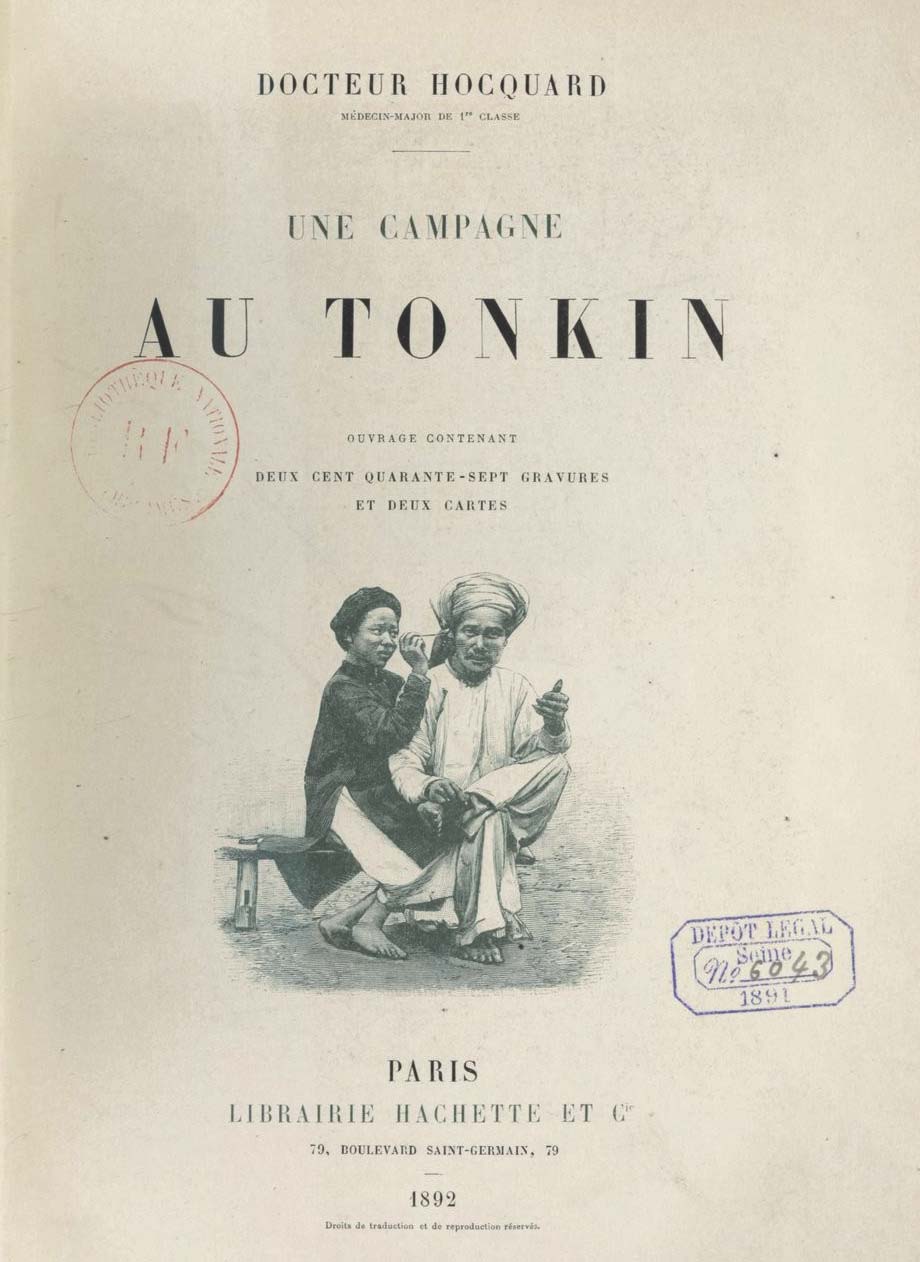

The geographical argument was never taken seriously into account by Vietnamese historians in the past because for them, this dynasty belonged to the mythical period. Moreover, according to Chinese writings, the territory of ancestors of the Vietnamese (Kiao-tche (Giao Chỉ)) was confined in the current Tonkin, thus annoying them to accept without explanation or justification the territorial spread of the Hồng Bàng dynasty until the Dongting lake. They did not see in the narration of this myth, the willingness of the ancestors of the Vietnamese to indicate their origin, to show their belonging in the Bai Yue group and their unwavering resistance facing formidable Chinese conquerors.

In the Chinese annals, one has reported that, at the Spring and Autumn period, Gou Jian king of the Yue state was interested to get an alliance with the Văn Lang kingdom in order to hold supremacy on other powerful principalities of the region. It is likely that the Văn Lang kingdom had to be a country neighbouring the state of Gou Jian king of Yue. This one had no interest in contracting this alliance if the Văn Lang kingdom was geographically confined in Vietnam today. The recent discovery of the Gou Jian king’s sword (reign of 496-465 before J.C.) in the grave n°1 of Wanshan (Jianling) (Hubei) allows to better discern the contours of the Văn Lang kingdom. It would probably be located in the Guizhou region (Qúi Châu). But Henri Masporo has contested this speculation in the book intituled « Le royaume de Văn Lang « (BEFEO, t XVIII, fasc 3 ) ». He has attributed to Vietnamese historians the mistake of confusing the Văn Lang kingdom with that of Ye Lang (or Dạ Lang in Vietnamese) the name of which has been badly by Chinese historians to their Vietnamese colleagues at the time of the Tang dynasty (nhà Đường). This is not exactly true because in Vietnamese legends, in particular in that of Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương (or Skylord of Phù Ðổng village), one realizes that the Văn Lang kingdom was in armed conflict with the Yin-Shang dynasty (Ân Thương) at the time of the Hùng VI king and it was much larger in area than the Ye Lang kingdom found at the time of the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng)

In the Vietnamese annals, one took about the long period of the Hùng kings reign (from 2879 to 258 before J.C.). The discovery of bronze artefacts in Ningxiang (Hu Nan) during the years 1960 does not put into question the existence of the contemporary centres of the Shang civilization ignored by writings in the southern China. There is the case of the culture of Sangxindui (Di chỉ Tam Tinh Đôi)(Sichuan (Tứ Xuyên)) for example. The wine vase in bronze decorated with the anthropomorphic faces testifies obviously to the contact established by the Shang with people of Melanesian type because one finds on these sides, the round human faces with a flat nose. The moulding of this bronze used in the manufacture of this vase requires the tin incorporation which the northern China did not have at that time.

Would there be any real contact, a war between the Shang and the Văn Lang kingdom if one held on to the legend of the skylord Phù Ðổng? Could you grant the veracity to a fact brought back by a Vietnamese legend ? Many western historians always perceived the Dongsonian civilization period as the beginning of the Vietnamese nation (500-700 before J.C.). It is also the shared opinion found in the anonymous historical work intituled « Việt Sử Lược« .

Under the reign of Zhuang Wang (Trang Vương) of Zhou (nhà Châu) ( 697-682 before J.C.), in the district Gia Ninh, there was a strange character managing to dominate all the tribes with his sorceries, taking for title the name Hùng and establishing his capital at Phong Châu. With the hereditary filiation, that made it possible for his line to maintain power with 18 kings, all bearing the name Hùng.

On the other hand, in other Vietnamese historical works, one granted a long period of reign to the Hồng Bàng dynasty (from 2879 to 258 before J.C.) with 2622 years. It appears inconceivable to us if one maintains 18 as the number of kings during this period because this means that each king Hùng reigned on average 150 years. One can only find a satisfactory answer if one accepts the assumption established by Trần Huy Bá in his expose published in the newspaper Nguồn Sáng n°23 on the commemorative day of Hùng kings (Ngày giỗ Tổ Hùng Vương) (1998). For him, there is a false interpretation on the word « đời » found in the sentence « 18 đời Hùng Vương« . The word « Ðời » must be replaced by the word Thời meaning « period ».

Mouth organ player

With this assumption, there are therefore 18 periods of reign, each of which corresponds to a branch being able to be made up of one or several kings in the family tree of the Hồng Bàng dynasty . This argumentation is reinforced by the fact that king Hùng Vương was elected for his courage and his merits if one refers to the Vietnamese tradition to choose men of value for the supreme function. That was reported in the famous legend of the sticky rice cake (Bánh chưng bánh dầy). One can thus justify the word Thời by the word branch (or chi ).

There is a need to give a more coherent explanation for the number 2622 with 18 branches following in the work intituled « Văn hoá tâm linh – đất tổ Hùng Vương » by the author Hồng Tử Uyên.

| Chi Càn | Kinh Dương Vương húy Lộc Túc |

| Chi Khảm | Lạc Long Quân húy Sùng Lãm |

| Chi Cấn | Hùng Quốc Vương húy Hùng Lân |

| Chi Chấn | Hùng Hoa Vương húy Bửu Lang |

| Chi Tốn | Hùng Hy Vương húy Bảo Lang |

| Chi Ly | Hùng Hồn Vương húy Long Tiên Lang |

| Chi Khôn | Hùng Chiêu Vương húy Quốc Lang |

| Chi Ðoài | Hùng Vĩ Vương húy Vân Lang |

| Chi Giáp | Hùng Ðịnh Vương húy Chân Nhân Lang |

| ………….. | manquant dans le document historique … |

| Chi Bính | Hùng Trinh Vương húy Hưng Ðức Lang |

| Chi Ðinh | Hùng Vũ Vương húy Ðức Hiền Lang |

| Chi Mậu | Hùng Việt Vương húy Tuấn Lang |

| Chi Kỷ | Hùng Anh Vương húy Viên Lang |

| Chi Canh | Hùng Triệu Vương húy Cảnh Chiêu Lang |

| Chi Tân | Hùng Tạo Vương húy Ðức Quân Lang |

| Chi Nhâm | Hùng Nghị Vương húy Bảo Quang Lang |

| Chi Qúy | Hùng Duệ Vương |

That enables us to also find the thread of history in the military conflict between the Văn Lang kingdom and the Shang via the legend of « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương (Thánh Gióng)« . If this conflict took place, it could only be at the beginning of the period of the Shang’s reign for several reasons:

- 1) No Chinese or Vietnamese historical document spoke about the trade between the kingdom of Van Lang and the Shang. On the other hand, one noted the contact established later between the Zhou dynasty (nhà Châu) and Hùng king. A silver pheasant had been offered even by this latter to the king of Zhou according to the book intituled « Selection of Strange Tales in Lĩnh Nam » (Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái).

- 2) The Shang dynasty only reigned from 1766 to 1122 before J.C. There would be approximately a time lag of 300 years if one tried to compute the arithmetic mean of the 18 periods under the Hùng kings reign: (2622/18) and to multiply it by 12 to give rougly a date to the end of the sixth branch of the Hùng reign ((Hùng Vương VI) by adding to which the number 258, the year of the annexation of the Văn Lang kingdom by An Dương king. One would have fallen about at the year 2006 dating the end of the sixth branch Hùng reign (Hùng Vuong VI). One can deduce from this date that the conflict if happened, should be at the beginning of the Shang dynasty era. This gap is not completely unjustified because one only has until then few precise historical details beyond the reign time of Chu Lệ Vương (Zhou LiWang) (850 before J.C.).

One notes a military expedition undertaken during three years by Wuding (Vũ Ðịnh) king of the Shang in the region of Ðộng Ðình lake against the nomadic people, the Gui alias « Demons », which was mentioned in the Yi King book (Kinh Dịch) translated by Bùi Văn Nguyên, Khoa Hoc Xã Hội Hà Nội 1997. In his work published in the newspaper Nguồn Sáng no 23, Trần Huy Bá rather thought of King Woding (Ốc Ðinh) who was one of the first kings of the Shang dynasty. With this assumption, there is no doubt or ambiguity because there is a perfect coherence reported in the Chinese and Vietnamese annals. One must know that at the time of An Dương Vương, one was accustomed to indicating the country Việt Thường under the name « Xích Qủi ». The term Xích is employed for referring to the equator (Xich đạo). About Qủi, this wants to evoke the red star Yugui Qui, one of the seven stars of the South. This one happened under the skies of the Jingzhou city of the Yue at the time the Shang king had installed his troop. It is also the opinion shared by the Vietnamese author Vũ Quỳnh in his work « Tân Ðinh Linh Nam Chích Quái »:

Ở đây có bộ tộc Thi La Quỷ thời Hùng Vương thứ VI vào đánh nước ta nhân danh nhà Ân Thương.

It is here that at the reign time of king Hùng VI , one found a tribe Thi La Qủy who invaded our country in the name of Yin-Shan.

This conflict could explain the principal reason for which the Văn Lang kingdom did not establish any trade with the Shang. The discoveries of the bronze objects in Ningxiang (Hu Nan) during the years 1960 gave the evidence that they could be the spoils brought back during the expedition into the southern China because there was no explanation to give to the bronze wine vases decorated with Melanesian anthropomorphic faces.

- 3°) In the Vietnamese legend « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương », one noted the escape and dislocation of the Shang army in the district Vũ Ninh at the same time the immediate disappearance of the celestial hero coming from the Phù Ðổng village. One also told of his spontaneous appearance at the time of the Shang invasion without any preparation in advance. This gave the evidence that he should be present on the territory at the invasion time of this latter. The territories conquered by the Shang could not be taken back entirely by the Lạc Việt because one could say that they were driven out of the Văn Lang territory in the legend. It was not completely the case because it was noted that with the advent of the Zhou dynasty, one saw appearing vassal countries like the state of Yue Goujian (Wu Yue) (Ngô Việt), the Chu kingdom ( Sỡ ) etc…on an old part of the Văn Lang territory.

It would not be known for whatever reason , the Văn Lang kingdom was reduced and thus confined in the north of Vietnam of today by glancing at the geographical map found during the time of Springs and Autumn and that of king Qin Shi Huang Di. Why was Goujian interested to the alliance with the Văn Lang kingdom if the latter was confined in the north of the Vietnam today? One could give to the dismemberment of this kingdom the following explanation:

At the time of the Yin-Shan invasion, a certain number of tribes among the 15 tribes of Lạc Việt people, succeeded in routing away the Shang army and continued to shown their attachment and their honesty to the Văn Lang kingdom. That did not prevent them from keeping their autonomy and maintaining a development rather high at the social and cultural level. That could give later an explanation to the emergence of independent states located at the geographical map of the Tsin period (Qin Shi Huang Di) as Ye Lang (Dạ Lang), Dian (Ðiền Việt), Si Ngeou (Tây Âu) and the significant reduction of the Văn Lang kingdom in area to the current state (in the north of Vietnam).

It is possible that this reduced kingdom restructured itself in an identical way sus as the Văn Lang kingdom established at the beginning of its creation by last king Hùng in order to remind to his people the greatness of his kingdom. The king thus kept the names of 15 ancient tribes and gave to his reduced territory the name Vũ Ninh for commemorating the brilliant success earned by Lạc Việt people under the reign of Hùng VI king. Việt Trì probably could be the last capital of the Văn Lang kingdom. One notes a part of historical reality in the Vietnamese legend because one has recently discovered in China the use of iron at the time of the Shang dynasty. On the other hand, the iron could be replaced by an other metal like the bronze without losing however the real significance in the content of the legend. It was only used for reflecting the courage and the bravery which one loved to attribute to the skylord. If the iron was well quoted, this no longer doubted its discovery and its use very early in the Văn Lang kingdom. This also justifies the coherence given by this legend to the conflict which opposed the Văn Lang kingdom and the Shang. Read more

Bibliography:

(1) Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

(2) Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

(3)Jīngzhōu (Kinh Châu) : la capitale de vingt rois de Chu, au cours de la période des Printemps et Automnes (Xuân Thu) (-771 — ~-481)

(4) Yángzhōu (Dương Châu)

(5) Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1.

(6) Edouard Chavannes :Mémoires historiques de Se-Ma Tsien de Chavannes, tome quatrième, page 170).

(7) Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin 1976 The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301