Yin and Yang numbers (Con số Âm Dương)

Version vietnamienne

Version française

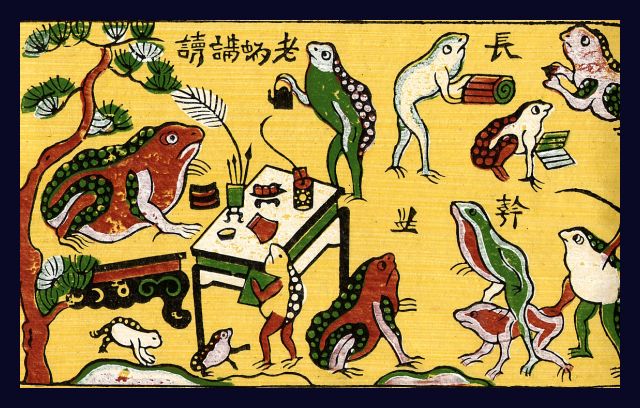

We are used to saying in Vietnamese: sống chết đều có số cả (Everyone has their D-day for life as well as for death). Ði buôn có số, ăn cỗ có phần (One has their vocation for trade just as one has their share at a feast). In everyday life, everyone has their size for clothes and shoes. It is noticed that, unlike the Chinese who adore even numbers, the Vietnamese rather favor odd numbers (số âm) over even numbers (số dương).

The frequent use of odd numbers is found in Vietnamese expressions: ba mặt một lời (One needs to be face to face in the presence of a witness), ba hồn bảy vía (three souls and seven vital supports for humans, i.e., one is panicked), Ba chìm bảy nổi chín lênh đênh (very turbulent), năm thê bảy thiếp (having 5 wives and 7 concubines, i.e., having multiple wives), năm lần bảy lượt (several times), năm cha ba mẹ (heterogeneous), ba chóp bảy nhoáng (hastily and carelessly), Một lời nói dối, sám hối 7 ngày (A lying word equals seven days of repentance), Một câu nhịn chín câu lành (Avoiding one offensive phrase is like having nine kind phrases), etc. or those involving multiples of the number 9: 18 (9×2) đời Hùng Vương (18 legendary Hùng Vương kings), 27 (9×3) đại tang 3 năm (27 months) (or a mourning period of three years which actually translates to only 27 months), 36 (9×4) phố phường Hà Nội (Hanoi with 36 districts), etc.

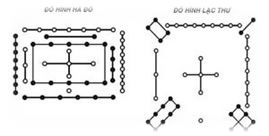

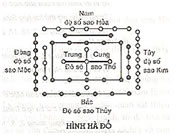

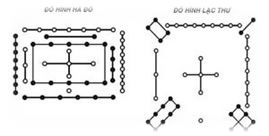

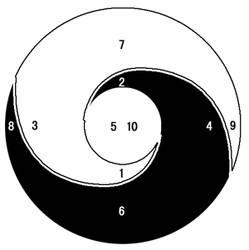

We must also not forget to mention the numbers 5 and 9, each having a very important role. The number 5 is the most mysterious number because everything begins from this number. Heaven and Earth have the 5 elements or agents (Ngũ hành) that give birth to all things and beings. It is placed at the center of the River Map (Hà Đồ) and the Luo River Writing (Lạc thư), which form the basis of the transformation of the 5 elements (Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Kim, Thổ) (Water, Fire, Wood, Metal, and Earth).

It is associated with the Earth element in the central position, which the farmer needs to know the direction of the cardinal points. This thus returns to man the center in managing things, species, and the four cardinal points. For this reason, in feudal society, this place was reserved for the king because he was the one who governed the people. Consequently, the number 5 belonged to him, as did the color yellow symbolizing the Earth. This explains the color chosen by Vietnamese and Chinese emperors for their garments.

Besides the center occupied by man, a symbolic animal is associated with each of the four cardinal points: the North by the turtle, the South by the phoenix, the East by the tiger, and the West by the dragon. It is not surprising to find at least in this attribution the three animals living in a region where agricultural life plays a significant role and water is vital.

Ho Tou Lo Chou

(Hà Đồ Lạc Thư)

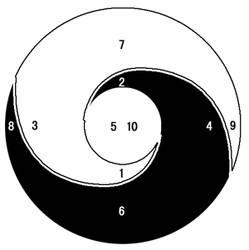

This is the territory of the Bai Yue. Even a dragon, so fierce in other cultures, becomes a gentle and noble animal imagined by the peaceful peoples of the Bai Yue. The number 5 is also known as « Tham Thiên Lưỡng Đia » (or ba Trời hai Ðất or 3 Yang 2 Yin) in the theory of Yin and Yang because obtaining the number 5 from the combination of the numbers 3 and 2 corresponds better to the reasonable percentage of Yin and Yang than that resulting from the combination of the numbers 4 and 1.

In the latter, one notices that the Yang number 1 is greatly dominated by the Yin number 4. This is not the case with the combination of numbers 3 and 2, where the Yang number 3 slightly dominates the (Yin) number 2. This favors the development of the universe in an almost perfect harmony. In the past, the fifth day, the fourteenth day (1+4=5), and the twenty-third day (2+3=5) of the month were reserved for the king’s outings. It was forbidden for subjects to conduct business during his travels and to disturb his walk. This may be the reason why many Vietnamese today, influenced by this ancestral tradition, continue to avoid choosing these days for building houses, traveling, and making important purchases. It is customary to say in Vietnamese:

Chớ đi ngày bảy chớ về ngày ba

Mồng năm, mười bốn hai ba

Đi chơi cũng lỗ nữa là đi buôn

Mồng năm mười bốn hai ba

Trồng cây cây đỗ, làm nhà nhà xiêu

Do not go on the seventh day, do not return on the third day

The fifth, fourteenth, twenty-third

Going out is also a loss, let alone trading

The fifth, fourteenth, twenty-third

Planting trees, the trees fail; building houses, the houses collapse.

You should avoid leaving on the 7th day and returning on the 3rd day of the month. On the 5th, 14th, and 23rd days of the month, you would be at a loss if you go out or do business. Similarly, you would see the fall of a tree or the tilting of your house if you plant it or build it on those days.

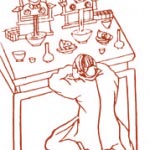

The number 5 is frequently mentioned in Vietnamese culinary art. The most typical sauce of the Vietnamese remains fish sauce. In the preparation of this national sauce, there are 5 flavors classified according to the 5 elements of Yin and Yang: salty (mặn) with fish juice (nước mắm), bitter (đắng) with lemon zest (vỏ chanh), sour (chua) with lemon juice (or vinegar), spicy (cay) with crushed or powdered chili peppers, and sweet (ngọt) with powdered sugar. These five flavors (mặn, đắng, chua, cay, ngọt) combined and found in the Vietnamese national sauce correspond respectively to the 5 elements defined in the Yin and Yang theory (Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Kim, Thổ) (Water, Fire, Wood, Metal, and Earth).

Similarly, these 5 flavors are found in the sweet and sour soup (canh chua) prepared with fish: sour with tamarind seeds or vinegar, sweet with pineapple slices, spicy with sliced chili peppers, salty with fish sauce, and bitter with some okra (đậu bắp) or with the flowers of the fayotier (bông so đũa). When this soup is served, a few fragrant herbs are added, such as panicaut (ngò gai), rau om (an herb with a flavor close to coriander but with an additional lemony note). This is a characteristic feature of the sweet and sour soup of Southern Vietnam and different from those found in other regions of Vietnam.

We cannot forget to mention the glutinous rice cake that the Proto-Vietnamese succeeded in passing down to their descendants over the millennia of their civilization. This cake is tangible proof of the belonging of the Yin and Yang theory and its five elements to the Hundred Yue, of which the Proto-Vietnamese were a part, because in the making of this cake, the generative cycle of these 5 elements (Ngũ hành tương sinh) found.

(Fire->Earth->Metal->Water->Wood)

Inside the cake, one finds a piece of porkmeat in red color ( Fire ) around which there is a kind of paste made with broad beans in yellow color ( Earth ). The whole thing is wrapped by the sticky rice in white color ( Metal ) to be cooked with boiling water ( Water ) before having a green colouring on its surface thanks to the latanier leaves (Wood).

There is another cake that cannot be missing at weddings. It is the susê or phu-Thê cake (husband-wife), which has a round shape inside and is wrapped in banana leaves (green color) to give it the appearance of a cube tied with a red ribbon. The circle is thus placed inside the square (Yang within Yin). This cake is made of tapioca flour, scented with pandan, and sprinkled with black sesame seeds. At the heart of this cake is a paste made from steamed soybeans (yellow color), lotus seed jam, and grated coconut (white color). This paste closely resembles the frangipane found in king cakes. Its sticky texture recalls the strong bond that one wishes to represent in the union. This cake is the symbol of the perfection of marital love and loyalty in perfect harmony with Heaven and Earth and the five elements symbolized by the five colors (red, green, black, yellow, and white).

This cake is recounted by the following tale: once upon a time, there was a merchant indulging in debauchery and not thinking of returning to his family, although before his departure, his wife gave him the susê cake and promised to remain warm and sweet like the cake. That is why, upon learning this news, his wife sent him other phu thê cakes accompanied by the following two verses:

Từ ngày chàng bước xuống ghe

Sóng bao nhiêu đợt bánh phu thê rầu bấy nhiêu

Since your departure, as many waves as were met by your boat, so many afflictions were known by the susê cake.

Lầu Ngũ Phụng

In architecture, the number 5 is not forgotten either. This is the case of the meridian gate of the Huế citadel, which is a powerful masonry mass pierced by five passages and topped with an elegant two-level wooden structure, the Belvedere of the Five Phoenixes (Lầu Ngũ Phụng).

Seen as a whole, it resembles a grouping of 5 phoenixes intimately perched with their wings spread. This belvedere has one hundred ironwood columns painted red, supporting its nine roofs. This number 100 has been carefully examined by Vietnamese specialists. For the renowned archaeologist Phan Thuận An, it corresponds exactly to the total number obtained by adding the two numbers found respectively in the River Map (Hà Ðồ) and the Luo River Script (Lạc thư cửu tinh đồ), symbolizing the perfect harmony of the union of Yin and Yang. This is not the opinion of another specialist, Liễu Thượng Văn. According to him, it represents the strength of 100 families or the people (bách tính) and reflects well the notion dân vi bản (taking the people as the foundation) in the governance of the Nguyễn dynasty.

The roof of the central pavilion is covered with yellow « lưu ly » tiles, the others with blue « lưu ly » tiles. The main gate, right in the middle, is the meridian gate (Ngọ Môn) paved with « Thanh » stones dyed yellow, dedicated to the passage of the king. On both sides, there are the Left Gate and the Right Gate (Tả, Hữu, Giáp Môn) reserved for civil and military mandarins. Then the two other side gates Tả Dịch Môn and Hữu Dịch Môn are intended for soldiers and horses. That is why it is customary to say in Vietnamese:

Ngọ Môn năm cửa chín lầu

Một lầu vàng, tám lầu xanh, ba cửa thẳng, hai cửa quanh »

The Meridian Gate has 5 passages and nine roofs, one of which is varnished in yellow and the other eight in green. There are three main doors and two side doors.

To the east and west of the citadel, there are the Gate of Humanity and the Gate of Virtue, which are reserved respectively for men and women.

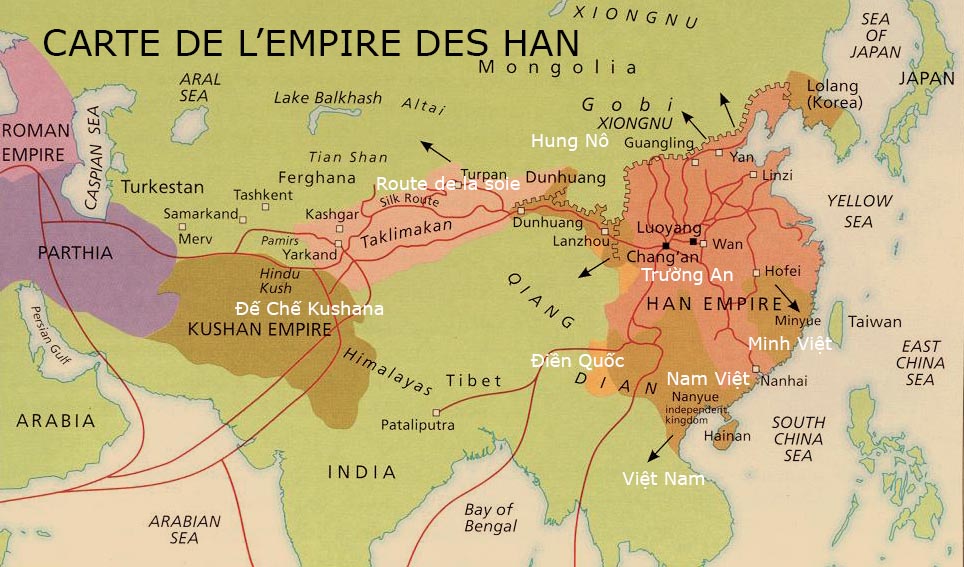

The number 9 is a Yang number (or odd). It represents the power of yang at its maximum and is difficult to reach. That is why in the past the emperor often used it to show his power and supremacy. He climbed the nine steps symbolizing the ascent of the sacred mountain where his throne was located. According to legend, the Forbidden City of Huế, like that of Beijing, had 9,999 rooms. It is worth recalling that the Forbidden City of Beijing was supervised by a Vietnamese named Nguyễn An, who was exiled at a very young age during the Ming dynasty. The emperor, like each of his palaces, faces south, towards the Yang energy, so that the emperor receives the vital breath of the sun because he is the Son of Heaven. In Vietnam, there are the nine dynastic urns of the citadel of Huế, the nine branches of the Mekong River, the nine roofs of the Five Phoenixes pavilion, etc. In the tale titled « The Mountain Spirit and the River Spirit (Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh), » the eighteenth (2×9) Hùng Vương king proposed as a dowry for his daughter Mị Nương’s marriage: an elephant with 9 tusks, a rooster with 9 spurs, and a horse with 9 red manes. The number 9 symbolizes the Sky, whose birth date is the ninth day of the month of February.

Less important than the numbers 5 and 9, the number 3 (or Ba or Tam in Vietnamese) is closely linked to the daily life of the Vietnamese. They do not hesitate to mention it in a great number of popular expressions. To signify a certain limit, a certain degree, they habitually say:

Không ai giàu ba họ, không ai khó ba đời.

No one can claim to be wealthy for three generations just as no one is unfortunate for three successive lives.

It often happens to the Vietnamese that they do not complete a certain task in one go, which forces them to perform the operation up to three times. This is the expression they frequently use: Nhất quá Tam. It is the number three, a limit they do not wish to exceed in accomplishing this task.

To say that someone is irresponsible, they refer to them as « Ba trợn. » One who is opportunistic is called Ba phải. The expression « Ba đá » is reserved for vulgar people, while those who keep getting entangled in small matters or endless troubles receive the title « Ba lăng nhăng. » To weigh their words, the Vietnamese need to fold the three thumbs of their tongue. (Uốn Ba tấc lưỡi).

The number 3 also is synonymous with insignificant and unimportant something.It is what one finds in following popular expressions:

Ăn sơ sài ba hột: To eat a little bit.

Ăn ba miếng: idem

Sách ba xu: book without values. (the book costs only three pennies).

Ba món ăn chơi: Some dishes for tasting.

Analogous to number 3, the number 7 is often mentioned in Vietnamese literature. One cannot ignore either the expression Bảy nỗi ba chìm với nước non (I float 7 times and I descend thee times if this expression is translated in verbatim) that Hồ Xuân Hương poetess has used and immortalized in her poem intituled « Bánh trôi nước” :

Thân em vừa trắng lại vừa tròn

Bây nỗi ba chìm với nước non

……….

for describing difficulties encountered by the Vietnamese woman in a feudal and Confucian society. This one did not spare either those having an independent mind, freedom and justice. It is the case of Cao Bá Quát , an active scholar who was degusted from the scholastica of his time and dreamed of replacing the Nguyễn authoritarian monarchy by an enlightened monarchy. Accused of being the actor of the grasshoppers insurrection (Giặc Châu Chấu) in 1854, he was condemned to death and he did no hesitate his reflection on the fate reserved to those who dared to criticize the despotism and feudal society in his poem before his death:

Ba hồi trống giục đù cha kiếp

Một nhát gươm đưa, đéo mẹ đời.

Three gongs are reserved to the miserable fate

A sabre slice finishes this dog’s life.

If the Yin and Yang theory continues to haunt their mind for its mystical and impenetrable character, it remains however a way of thinking and living to which a good number of the Vietnamese continue to refer daily for common practices and respect of ancestral traditions.

Bibliography

–Xu Zhao Long : Chôkô bunmei no hakken, Chûgoku kodai no nazo in semaru (Découverte de la civilisation du Yanzi. A la recherche des mystères de l’antiquité chinoise, Tokyo, Kadokawa-shoten 1998).

-Yasuda Yoshinori : Taiga bunmei no tanjô, Chôkô bunmei no tankyû (Naissance des civilisations des grands fleuves. Recherche sur la civilisation du Yanzi), Tôkyô, Kadokawa-shoten, 2000).

-Richard Wilhelm : Histoire de la civilisation chinoise 1931

-Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

– Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1

-Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

-Dich Quốc Tã : Văn Học sữ Trung Quốc, traduit en vietnamien par Hoàng Minh Ðức 1975.

-Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin (1976) : The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

-Henri Maspero : Chine Antique : 1927.

-Jacques Lemoine : Mythes d’origine, mythes d’identification. L’homme 101, paris, 1987 XXVII pp 58-85

-Fung Yu Lan: A History of Chinese Philosophy ( traduction vietnamienne Đại cương triết học sử Trung Quốc” (SG, 1968).68, tr. 140-151)).

-Alain Thote: Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine.

-Cung Ðình Thanh: Trống đồng Ðồng Sơn : Sự tranh luận về chủ quyền trống

đồng giữa h ọc giã Việt và Hoa.Tập San Tư Tưởng Tháng 3 năm 2002 số 18.

-Brigitte Baptandier : En guise d’introduction. Chine et anthropologie. Ateliers 24 (2001). Journée d’étude de l’APRAS sur les ethnologies régionales à Paris en 1993.

-Nguyễn Từ Thức : Tãn Mạn về Âm Dương, chẳn lẻ (www.anviettoancau.net)

-Trần Ngọc Thêm: Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt-Nam. NXB : Tp Hồ Chí Minh Tp HCM 2001.

-Nguyễn Xuân Quang: Bản sắc văn hóa việt qua ngôn ngữ việt (www.dunglac.org)

-Georges Condominas : La guérilla viêt. Trait culturel majeur et pérenne de l’espace social vietnamien, L’Homme 2002/4, N° 164, p. 17-36.

-Louis Bezacier: Sur la datation d’une représentation primitive de la charrue. (BEFO, année 1967, volume 53, pages 551-556)

-Ballinger S.W. & all: Southeast Asian mitochondrial DNA Analysis reveals genetic continuity of ancient Mongoloid migration, Genetics 1992 vol 130 p.139-152….