Hôn Nhân

More than the eternal world law, it first appears that marriage in Vietnam is an alliance of families aiming at perpetuating not only the race but also the Vietnamese customs, especially the cult of ancestors.

Moreover, Vietnamese people, imbued with Taoist spirit, consider that youth has only a limited time like that of a bamboo shoot. Therefore people had the habit of marrying early in the old days in Vietnam.

Similar to the Ming Code in China, the Lê Code provided the minimal age of marriage at 13 for girls and 16 for boys. That is why in a Vietnamese proverb, it is said:

Gái thập tam, nam thập lục

ou in English

Girls at thirteen, boys at sixteen

that Vietnamese society allows for marriage. It is always done in accordance with the Confucian tradition. It is always preceded by negotiations led by matchmakers and followed by exchange of astrological data if first contacts proved to be convincing.

This, in a general manner would lead to the promise of marriage which should be kept under penalty of fines imposed by local mandarins in the old days. The engagement ceremony is also an occasion to confirm the definite commitment to marriage.

As for the latter, it occurs following a ceremonial standard to include the arrival of the future wife in palanquin, her discovery by the fiance, a ritual ceremony of offering before the altar of ancestors, then before the spouses’ parents, the holding of hands and the exchange of oath.

However, the same word is not used to refer to the marriage of a princess or an ordinary girl. « Hạ Giá » is used when it comes to the marriage of a princess because the king gives his daughter’s hand to someone less powerful than he, and of lower ranking. ( Hạ means « below » and Giá means « Marry »). For marriages between normal people, Xuất Giá is used because Xuất means « exit ». In the old days, rarely did the spouses know each other before getting married.

The marriage was considered an arrangement between parents aiming at honoring a debt or contracting an alliance. It reflects also the Confucian state of mind not to be in favor of the predominance of the individual over family and society. The marriage of princess Huyền Trân to the Champa king Chế Mẫn ( Jaya Simhavarman III ) illustrated well this state of mind.

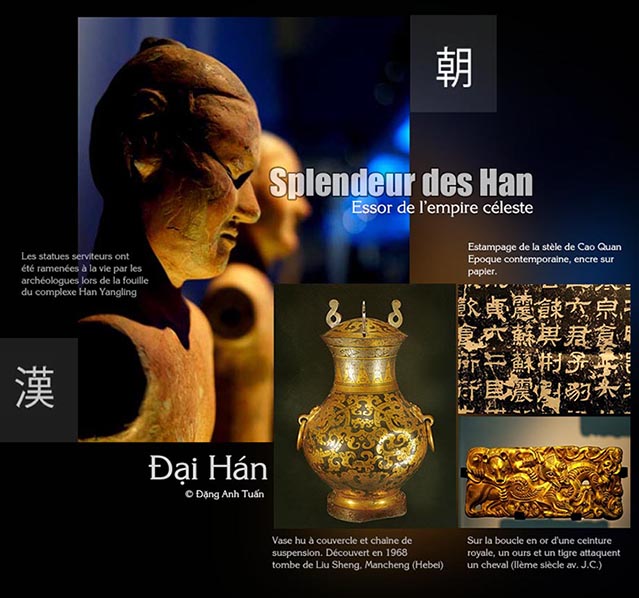

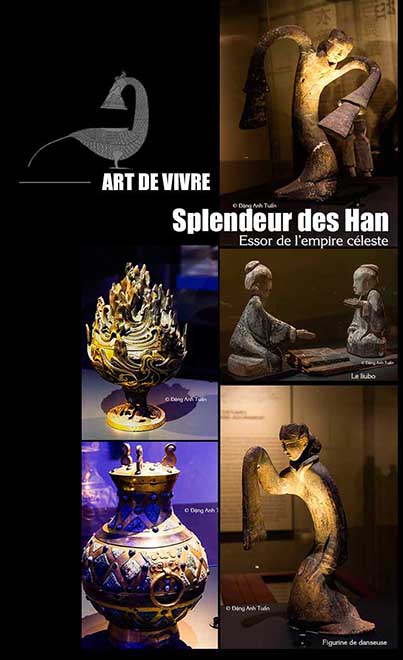

For territorial ambitions, it was difficult for king Trần Anh Tôn to ignore the promise made by his father, king Trần Nhân Tôn to give the hand of his sister to the king of Champa although he was aware of her love to general Trần Khắc Chung. An anonymous author at the time did not hesitate to denounce it in his Tang style, seven-foot poems entitled Vương Tường, comparing princess Vương Tường ( or Wang Zhaojun in Chinese ), a concubine of the Han emperor, Yuandi ( Hán Nguyên Ðế )(48-33 B.C.) destined to the king of Xiongnu ( shanyu Huhanxie ) in the goal of restoring peace with the barbarians coming from the steppes North of China.

In spite of that, there is in the annals of marriages the case of general Trần Quốc Tuấn where love triumphed over reason and the will of the parents although he was known as a very convinced confucianist. When he was young, he fell in love with princess Thiên Thành, king Trần Thái Tôn’s sister who did not even hide her admiration for this talented general.

But it was forbidden for him to materialize his intention because his father, An Sinh Vương Trần Liễu opposed that union, having been forced by the machiavellian prime minister Trần Thủ Ðộ. at that time to yield his concubine, princess of the Ly, Thuận Thiên to his brother, king Trần Thái Tôn in the goal of perpetuate the dynasty. One day having learned that the king has granted the hand of his sister Thien Thanh to the son of Nhân Ðạo Vương, he was stunned and so sad that he did not know what to do although at that time he was known to be the best strategist in the struggle against the Mongols.

Seeing him distraught, one of his aides known to be the most cunning suggested he seize the fiancee by surprise on the wedding day. Thanks to this extraordinary boldness, he succeeded in materializing his love, obtaining the king’s pardon and conquering the esteem of his entourage, in particular that of his father because the latter found in him not only a man of genius but also a son worthy and capable of cleansing the shame of the family. Marriage is sometimes the source of worry for those who assume a responsibility or a political role on this land of legends.

It is the case of emperor Duy Tân. Obsessed by his father emperor Thành Thái’s deposition and exile by the colonial authorities, Duy Tân since his coming up to the throne at age 7, has relentlessly nourished the intention of reopening the whole question the Patenôtre Treaty and reestablishing Vietnam’s sovereignty and independence by all means including force. He never thought of getting married as long as the country is under foreign occupation.

This has caused a lot of worry and anxiety for his mother, queen Nguyễn Thị Ðịnh. She saw in her son the immaturity and lack of authority toward his people because Duy Tan did not have any descendants. She hurriedly presented to the emperor a list of 25 young noble girls chosen

and provided by the mandarins. But facing Duy Tan’s disinterest and impassibility, she was furious and ordered him to look for a concubine within a short time. Being a pious son, he knew he could no longer delay the deadline and ignore his mother’s insistence. He replied with an impassible tone:

Up to now I have refused your list because I have long been in love with another girl one year older than I. This one, I am going to see her in ten days at the Cửa Tùng beach.

Puzzled, the queen mother decided to join him during his walk at the Cửa Tùng beach. Duy Tan spent the whole day searching in the sand. In the evening, the queen mother decided to ask:

Don’t you find it ridiculous to look for your darling in the sand?

Duy Tân tried to provide an explanation with modesty:

I am never that nutty. All I told you is true. If we cannot find gold in the sand, we can find it in the capital Huế.

From then on the queen mother began to grasp the hint Duy Tân had evoked. It has something to do with the daughter of his teacher named Mai Thị Vàng. ( Vàng means gold in English ).

Intrigued by her son’s choice, the queen mother asked him one more time:

For what reason do you choose her?

Duy Tân replied with conviction:

Her father Mai Khắc Ðôn has taught me to read, to love the country, to avoid sycophants and to make use of loyal servants. I infer he would teach his daughter the same thing, wouldn’t he, mother?

By this marriage, emperor Duy Tân has shown us he knew how to be up to his mother’s expectation in showing his gratitude to his teacher, the man who has taught him love this country and in choosing a wife having the same conviction and ideal as he and not becoming a hindrance to his political fight.

It is also for the love of Vietnam and for the same fight that nationalist leader Nguyễn Thái Học and his party comrade Nguyễn Thị Giang vowed to each other to become husband and wife at the altar of ancestors just before their uprising in Yên Bái. They promised to get married later, once their plan It is also for the love of Vietnam and for the same fight that nationalist leader Nguyễn Thái Học and his party comrade Nguyễn Thị Giang vowed to each other to become husband and wife at the altar of ancestors just before their uprising in Yên Bái. They promised to get married later, once their plan is realized. To show her determination and to seal their fate, Nguyễn Thị Giang asked her husband for a revolver. It was with this weapon that she killed herself after having known of the failure of the uprising and the death sentence of her husband and his compatriots by the colonial authorities.

For several Vietnamese generations, she has become on that date, like her husband, « nhân » ( nhân means Người or an exemplary human being in English ) because Nguyễn Thái Học had the habit of telling his comrades before his death:

Không thành công thì thành nhân.

One becomes exemplary human being without being successful.

Nowadays marriage is not as precocious as before, even in the rural areas. This deferment helps protect the mother against the effects of teen age pregnancy and limit births. Marriage is no more the result of the will of parents or the alliance of families. On the other hand it no longer bears a symbolical value, a particular meaning because the newly weds often know each other before marriage in most cases. It no longer reflects the sacrifice asked of young weds to perpetuate the cult of ancestors and the race. It is first and foremost the consecration of love and the pledge for better or for worse ( duyên nợ in Vietnamese) to all eternity.