Từ bao giờ có khu 36 phố phường ở Hà Nội?

Depuis quand il y a le quartier des 36 rues et corporations à Hanoï?

Version française

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

Thăng Long được xuất phát từ làng Long Đỗ. Từ thế kỷ thứ năm, vua Lý Nam Đế đã xây ở đây « mộc thành» của nước Vạn Xuân. Nhà Đường, sau khi xâm chiếm nước ta lấy nơi nầy làm trị sở trên đất Long Đỗ và đổi tên nó ra Tống Bình.

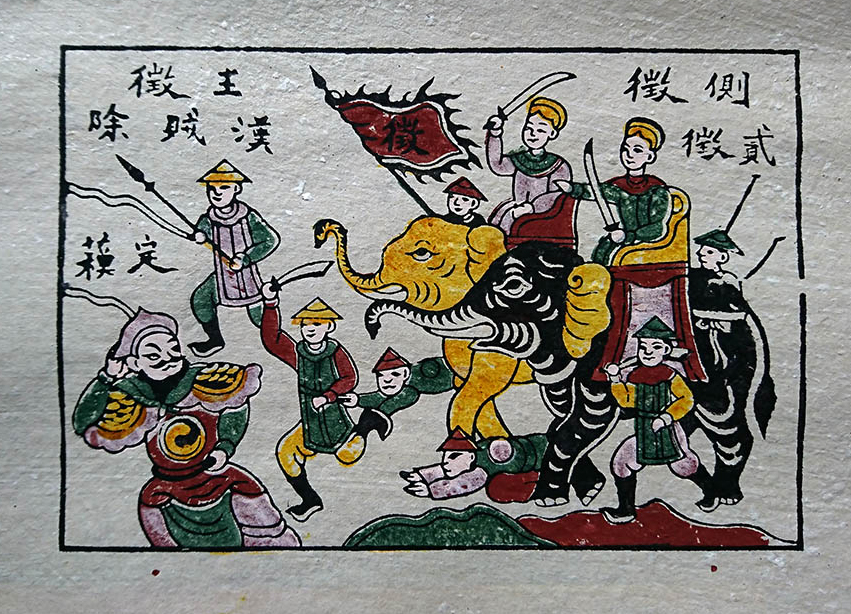

Lý Công Uẩn dưới sự giúp đở của sư Vạn Hạnh nhận ra tiềm năng của vùng đất nầy vì nó là điểm giao nhau của các trục đường bộ và đường sông trong việc vận chuyễn hàng hóa. Vã lại nó còn đáp ứng cho việc cân bằng giữa các yếu tố nước và đất hay là giữa dòng khí tốt (Rồng xanh) và dòng khí xấu (hổ trắng) trong phong thủy mà được tướng nhà Đường Cao Biền du nhập vào nước ta. Tục truyền Cao Biền dùng bùa phép yểm trấn thành Đại La nhưng nhờ thần Bạch Mã trợ giúp mà Lý Thái Tổ thành công trong việc xây thành Thăng Long trên nền móng cũ của thành Đại La. Đền thờ Bạch Mã vẫn còn ngày nay ở phố Buồm (Rue des voiles). Vì vậy vào mùa thu 1010, Lý Công Uẩn mới ra quyết định dời đô từ Hoa Lư về vùng đất « Rồng cuộn, hổ ngồi ». Ngài muốn chọn một nơi để phát triển kinh tế cho vận nước được lâu dài và tính kế lâu dài cho con cháu được muôn vạn thế hệ và muôn vật được phồn thịnh và phong phú.

Từ đó, ngài cần lập các công xưởng thủ công để sản xuất các hàng hóa mà triều đình cần dùng và tiêu thụ. Không những các thợ thụ công giỏi đua nhau đến Thăng Long làm việc mà luôn cả các nông dân ở thôn quê vùng sông Hồng lúc nhàn rỗi cũng tham gia sản xuất các sản phẩm hàng thủ công bán cho các con buôn mà những người này họ mang về kinh thành bán lại để kiếm lời. Lúc đầu họ tụ hợp ở các phiên chợ của bốn chợ lớn tại các cửa ô kinh thành. Nhưng về sau vì các xưởng sản xuất của triều đình không thể cung ứng đủ nên khiến một số thương nhân dần dần tập trung tại khu phố ở cửa Đông vì ở đây địa thế của chợ nầy rất thuận lợi cho việc chuyên chở hàng hóa bằng thuyền từ nông thôn ra kinh thành qua sông Hồng, Tô Lịch và các kênh. Phía trước mặt chợ thời đó là đền Bạch Mã. Còn bên phải là sông Tô Lịch và thưở đó có cái cầu bắc ngang sông hiện nay đó là phố Hàng Đường. Bởi vậy ở thế kỉ 14 mới có thành ngữ « Kẻ Chợ » (những người của chợ) để nói đến khu phố tấp nập này. Chính nơi nầy được gọi về sau là khu 36 phố phường để bán các sản phẩm thủ công mà các làng nghề xung quanh và ở nông thôn cung cấp. Các cửa hàng đều là những nhà chòi dùng để làm cơ xưởng hay để buôn bán dọc theo phố (hay đường).

Tựa như các nhà ở đồng quê, các cửa hàng nầy được dựng lên bằng gỗ, tre, mái rơm và tường trét bùn. Nhà nào cũng có chum nước để ở trên mái khi có hỏa họan thì kéo đổ xuống mái. Quá sợ hỏa hoạn, người dân lập đền Hỏa Thần (nay nó nằm ở Hàng Điếu) để ngày rằm cầu xin thần lửa đừng gây cháy. Kẻ Chợ dần dần thoát khỏi sự phụ thuộc vào kinh thành từ thế 17 dưới sự ngự trị của các chúa Trịnh nhờ có một loạt nghị quyết như giảm thuế, thống nhất hệ thống tiền bạc và xây dựng nhiều công trình đô thị lớn dẫn đến sự phát triển đáng kể. Các thủ công nhà buôn từ các làng nghề đổ xô về cư ngụ lâu dài ở thành phố và các nhà con buôn nước ngoài thì bắt đầu lập chi nhánh tại kinh thành khiến làm nền kinh tế nó rất sôi động hơn. Nhờ đó mà kinh thành trở nên trung tâm buôn bán lớn nhất của miền bắc Việt Nam.

Các thợ thủ công và các thương nhân cùng một làng quê gốc tập hợp thành các phương hội rồi cùng nhau chuyên sản xuất hay bán ở phường. Để kiếm hàng cần mua thì chỉ cần đến phường mà trước lối cổng vào thì có một tấm bảng ghi rõ chất lượng và loại hàng được bán.Thời kỳ này chữ phố cũng chưa được dùng. Theo nhà văn Nguyễn Ngọc Tiến thì chữ phố vẫn được dùng với nghĩa là bến sông. Bởi vậy mới có câu « Gác mái ngư ông về viễn phố » (nhớ về bến xa) trong bài thơ « Chiều hôm nhớ nhà » của bà Huyện Thanh Quan.Theo nhà sử học Pháp Philippe Papin, thì chữ phố được sử dụng vào năm 1851 ở huyện Thọ Xuyên và Vĩnh Thuân nên mới có chức trưởng phố trong quyến sách mang tựa đề là « Lịch sử Hà Nội ». Còn trong sách Đại Nam nhất thống chí thì có chép như sau: Hà Nội là kinh đô xưa, nguyên trước có 36 phố phường …. Còn trong cuốn « Chuyến đi thăm Bắc Kỳ năm Ất Hợi (1876) của học giả Trương Vĩnh Ký thì ông có kể ra 21 phố gồm có: Hàng Buồm, phố nầy cũng là phố Khách Trú có nhiều tiệm thuốc bắc, nhiều hàng cao lâu, Hàng Quảng Đông (Hàng Ngang hiện nay) nơi nầy cũng toàn người khách trú ở, Hàng Mã thì gắn liền với nghề sản xuất, buôn bán đồ giấy, đồ vàng mã cúng lễ, ma chay vân vân… Như vậy chữ phố có thể ra đời từ đầu thời vua Tự Đức.

Các thợ kim hoàn xuất phát từ làng Châu Khê thì định cư ở phố Hàng Bạc. Còn thợ tiện gỗ đến từ làng Nhị Kê thì ở phố Tô Tịch vân vân…Họ luôn luôn giữ liên lạc với ngôi làng gốc của họ ở nông thôn trong việc tuyển nhân công, cung ứng nguyên liệu, ghi tên vào gia phả của làng, tham gia mỗi năm và các ngày hội của làng.

Các làng ở nông thôn trở thành các nơi cung cấp không những cho làng phố đô thị các sản phẩm đạt trình độ kỹ thuật cao mà còn luôn cả nông phẩm cho kinh thành. Có thể nói các làng ở nông thôn và các làng phố ở kinh thành phụ thuộc lẫn nhau. Chính nhờ thế tình thần đoàn kết giữa các làng phố đô thị và các làng ở nông thôn càng chặt chẽ hơn nữa. Mỗi làng phố đô thị được xây dựng dọc theo phố hay một đoạn của phố và lệ thuộc một hay nhiều làng cùng làm một nghề thủ công. Thời đó đăc điểm của làng phố là ở mỗi đầu của làng phố là có cổng ra vào. Các cổng nầy đều đóng lại lúc về đêm. Mỗi làng phố còn có một bộ máy hành chánh riêng biệt cũng như có một trưởng phố, một ngôi đình riêng tư nhầm để thờ các ông tổ của nghề hay là các thần hoàng của các làng gốc ở nông thôn. Dưới thời Pháp thuộc, để tránh hỏa hoạn thì chính quyền Pháp mới ra chỉ thị xây dựng lại thành phố qua các công trình kiến trúc kiên cố với các ngôi nhà hình ống mà chúng ta được thấy ngày nay ở phố cổ Hà Nội mà họ còn lấp đi nhiều ao hồ như hồ Hàng Đào, hồ Mã Cảnh, hồ Hàng Chuối, hồ Liên Trì vân vân… Năm 1894, Pháp lấp đọan đầu sông Tô Lịch để xây chợ Đồng Xuân. Họ lại phá tường thành Hà Nội và các cửa thành. Nay chĩ còn duy nhất Ô Quan Chưởng hay (Ô cửa Đông) còn khúc sông Tô Lịch dưới chân thành cũng bị lấp đi. Giờ đây nhiều phố chỉ còn tên mà thôi như phố Hàng Bè chớ cát bồi đưa sông ra xa nên bè mảng không còn vào được sát chân đê nữa. Như vậy đâu còn bè mà cũng không còn chợ cái bè trên đê nữa.

Còn các nhà hình ống nầy mang đậm phong cách phương tây nhất là mặt tiền với ban công, lô gia, hiên nhà vân vân. Còn vật liệu xây dựng thì gồm có xi măng, cốt thép, bê tông, kính vân vân … Tuy nhiên theo sử gia Pháp Philippe Papin thì các nhà ống ở Hànội là ảnh hưởng của cộng đồng người Hoa. Luận chứng nầy không hẳn là sai nếu có dịp đến tham quan các nhà cổ của người Hoa ở Hội An. Nhưng theo nhà văn Nguyễn Ngọc Tiến thì dưới thời vua Minh Mạng, đánh thuế cửa hàng không căn cứ nhà đó buôn to hay nhỏ hay chiều sâu mà chỉ đo mặt tiền. Mặt tiền rộng đóng thuế cao, hẹp thì thuế ít. Vì vậy mặt tiền rộng hay thường chia ra nhiều cửa hàng. Đôi khi con trai lập gia đình và không có điều kiện mua chỗ buộc cha mẹ phải nhường một phần cửa hàng nên mới có sự hình thành nhà ống. Các nhà ống tuy mặt tiền rất eo hẹp nhưng có thể có chiều dài lên đến 60 thước. Loại nhà nầy thường có ba phần: phiá trước dùng để buôn bán hay cơ xưởng còn ở giữa hay thường có cái sân, nơi có một nhà nhỏ xây vòm cuống giống một cái lò cao 1,8 thước để chứa các đồ qúi giá phòng khi cháy chớ nếu không mất trắng tay và phần cuối thì để ở.

Trong quyển sách được mang tên là « Miêu tả về vương quốc Bắc Kỳ », ông Samuel Baron, một thương gia người Anh có nhắc đến phố cổ qua một số tài liệu hình ảnh và những gì ông mô tả thật thú vị. Tuy rằng nhỏ hẹp so với diện tích của Việt Nam, khu phố cổ Hà Nội nó là minh chứng tiêu biểu của nền văn hóa thương mại và đô thị của người dân Việt qua nhiều thế kỷ. Đây là một kiểu mẫu mà cần thiết phải biết tường tận để hiểu rõ được cái cấu trúc truyền thống của đô thị trong thế giới làng mạc của người dân Việt.

Version française

Thăng Long était issue du village de Long Đỗ. Dès le Vème siècle, le roi Lý Nam Đế construisit ici la « citadelle en bois » du royaume de Vạn Xuân. Après avoir envahi notre pays, la dynastie des Tang a pris cet endroit comme le quartier général de son armée sur les terres de Long Đỗ et a changé son nom en Tống Binh. Lý Công Uẩn aidé par le moine Van Hanh, a trouvé l’énorme potentiel de cet endroit car il était à l’intersection des routes et des voies fluviales pour faciliter le transport de marchandises. De plus, il a répondu également à l’équilibre et l’harmonie entre les éléments Eau et Terre ou bien entre le souffle bienfaisant (Dragon vert) et le souffle malfaisant (Tigre blanc) dans la géomancie introduite dans notre pays par le général Tang Gao Pian. La légende racontait qu’il se servit des sortilèges pour protéger la citadelle de Đại La, mais grâce à l’aide apportée par le génie « métamorphosé en Cheval Blanc », Lý Thái Tổ réussit à édifier la citadelle de Thăng Long sur les anciennes fondations de la citadelle de Đại La. Le temple dédié au culte du Cheval Blanc existe encore aujourd’hui dans la rue des voiles (Phố Buồm). C’était pourquoi à l’automne 1010, Lý Thái Tổ vint de décider le transfert de la capitale, de Hoa Lư à la région où le dragon s’enroulait et le tigre était assis. Il voulait choisir un endroit pour développer l’économie à long terme et prévoir un avenir radieux avec prospérité et abondance pour dix mille générations futures.

Il dut créer dès lors des usines artisanales pour produire les marchandises dont la cour royale avait besoin pour la consommation. Il y avait non seulement des artisans talentueux se précipitant à travailler à Thăng Long, mais aussi des agriculteurs vivant dans les campagnes de la région du fleuve Rouge. Ces derniers, durant leur temps libre, ont également participé à la production de produits artisanaux destinés à être vendus aux intermédiaires qui les ont ramenés dans la capitale pour les revendre dans le but de gagner de l’argent. Dans un premier temps, ils s’étaient rassemblés aux quatre grands marchés se trouvant tout près des portes de la capitale. Mais comme les usines royales ne pouvaient pas approvisionner suffisamment les produits, ils s’étaient progressivement regroupés dans le quartier de la Porte Est car le terrain d’ici était très propice au transport fluvial des marchandises de la campagne vers la capitale en passant par le fleuve Rouge jusqu’à Tô Lich et les canaux.

À cette époque, devant le marché se trouvait le temple du Cheval Blanc (Bạch Mã). Sur sa droite il y avait la rivière Tô Lich et un pont, le tout devenant aujourd’hui la rue du sucre (Hàng Đường). C’était pourquoi au 14ème siècle l’expression « Kẻ Chợ » (ou les gens du marché) était employé pour désigner ce quartier animé. C’était cet endroit qui devenait plus tard le quartier de 36 rues et corporations destiné à vendre tous les produits artisanaux fournis par les villages artisanaux et ruraux aux alentours. Les magasins étaient entièrement des huttes utilisées comme des ateliers de fabrication ou des lieux pour faire du commerce tout le long de la rue.

Analogues à des maisons de campagne, ces magasins étaient construits en bois et en bambou, avec des toits de paille et des murs enduits de boue. Chaque maison possédait une jarre d’eau sur le toit qui, en cas d’incendie, pouvait être renversée sur le toit pour éteindre le feu. Étant effrayés par le feu, les gens ont décidé de construire un temple destiné au génie du feu (situé aujourd’hui dans la rue des pipes) pour lui demander de ne pas provoquer d’incendie tout le 15ème jour du mois lunaire. Kẻ Chợ s’’était progressivement échappé de la dépendance de la capitale depuis le XVIIème siècle sous le règne des seigneurs Trinh grâce à une série de résolutions telles que la réduction des impôts, l’unification du système monétaire et la réalisation de nombreux projets urbains conduisant à un développement important. Les artisans commerçants des villages artisanaux affluèrent vers la capitale pour y vivre de manière permanente et les commerçants étrangers commencèrent à ouvrir aussi des succursales dans la capitale, ce qui rendait l’économie plus dynamique. Grâce à cela, la capitale était devenue ainsi le plus grand centre commercial dans le nord du Vietnam.

Les artisans et les commerçants d’un même village se regroupaient en corporations et se spécialisaient ensemble dans la production ou la vente dans le quartier. Pour trouver les produits dont vous avez besoin, il vous suffit de vous rendre au quartier dont le portail d’entrée porte un panneau indiquant clairement la qualité et le type de produits vendus. Durant cette période, le mot rue n’était pas utilisé. Selon l’écrivain Nguyễn Ngoc Tiến, le mot rue était encore employé pour désigner le quai fluvial. C’est pourquoi il y a la phrase « En déposant la rame, le pêcheur se dépêche de retourner à la rive lointaine » dans le poème «L’après-midi teinté de nostalgie» de Mme Huyện Thanh Quan. Selon l’historien français Philippe Papin, le mot « rue » était utilisé en 1851 dans les districts de Thọ Xuyên et Vĩnh Thuận. C’est pour cela que le poste du chef de la rue est apparu dans son livre intitulé « Histoire de Hanoi ».

Dans le livre intitulé Đai Nam Nhất Thống Chí (Géographie du Viet Nam), il est écrit ainsi: Hanoï était l’ancienne capitale, elle comptait à l’origine 36 rues etc. Dans le livre « Un voyage au Tonkin de l’année du cochon en bois (1876) » de l’érudit Trương Vĩnh Ký, il a répertorié 21 rues dont: Hàng Buồm (Rue des voiles). Cette rue étant aussi la rue des immigrants chinois avec de nombreux magasins de médecine traditionnelle et des restaurants chinois , Hàng Quảng Đông c’était la rue des Cantonnais à l’époque française (rue Hang Ngang d’aujourd’hui), Hàng Mã (Rue du cuivre à l’époque française) était associée à la production et au commerce de papiers votifs, des objets de funérailles, etc. Le mot rue pourrait donc être né dès le début du règne du roi Tự Đức.

Les bijoutiers venus du village de Châu Khê s’étaient installés dans la rue des changeurs (Hàng Bạc). Quant aux tourneurs sur bois du village de Nhi Kê, ils habitaient dans la rue Tô Tịch et ainsi de suite… Ils gardaient toujours le contact avec leur village d’origine à la campagne en recrutant des ouvriers, en fournissant du matériel, en inscrivant leurs noms dans la généalogie du village et en participant chaque année aux fêtes villageoises.

Les villages ruraux étaient devenus ainsi des lieux qui approvisionnaient non seulement les villages urbains en produits de haute technologie mais aussi en produits agricoles pour la capitale. On peut dire que les villages de la campagne et les villages de la capitale dépendaient les uns des autres. Grâce à cette interdépendance, l’esprit de solidarité entre les villages urbains et les villages ruraux était encore plus serré. Chaque village urbain était construit le long d’une rue ou d’un tronçon de rue et dépendait d’un ou plusieurs villages exerçant le même métier.

A cette époque, la particularité du village résidait sur le fait qu’à chaque extrémité du village il y avait toujours un portail d’entrée qui était fermé durant la nuit. Chaque village disposait également d’un appareil administratif distinct ayant un chef de village, une maison communale dédiée au culte des ancêtres du métier ou des génies du village dont les gens étaient issus.

Durant la période coloniale française, afin d’éviter les incendies, le gouvernement français prit la décision de réorganiser la ville au moyen des travaux architecturaux avec des maisons tubulaires que l’on voit aujourd’hui dans la vieille ville de Hanoï, mais il fit disparaître également de nombreux étangs et lacs comme le lac Hàng Đào, lac Mã Cảnh, lac Hàng Chuối, lac Liên Trì etc. pour construire les maisons et les bâtiments publics. En 1894, les Français ont asséché la partie supérieure de la rivière Tô Lich pour construire le marché de Đồng Xuân. Ils ont de nouveau détruit les murs de la citadelle de Hanoi et ses portes. Il ne restait désormais que la porte Quan Chưởng (porte de l’Est) et la rivière Tô Lich en contrebas de la citadelle a également été comblée de sable et d’alluvions. À présent, de nombreuses rues n’ont plus que leur nom, comme la rue Hàng Bè (rue des radeaux), car le sable a repoussé la rivière plus loin, de sorte que les radeaux ne peuvent plus s’approcher du pied de la digue. Donc il n’y a plus de radeau. Alors il n’y a non plus de marché des radeaux sur la digue.

Quant aux maisons tubulaires, on les voit mettre en valeur le style occidental, notamment leur façade avec balcon, loggia, porche etc. Les matériaux de construction comprennent le ciment, les barres d’armature, le béton, le verre etc. Cependant, selon l’historien français Philippe Papin, les maisons tubulaires de Hanoï sont influencées par la communauté chinoise. Cet argument n’est pas forcément faux si on a l’occasion de visiter les anciennes maisons des Chinois à Hội An. Mais selon l’écrivain Nguyễn Ngoc Tiến, sous le règne du roi Minh Mang, l’impôt sur les magasins n’était pas basé sur la taille ou la profondeur du magasin, mais uniquement sur la façade. Le propriétaire d’un magasin ayant une façade relativement large doit payer une taxe plus élevée par rapport à celui possédant une petite façade. On a intérêt de diviser la grande façade en plusieurs petites façades donc en plusieurs boutiques. Parfois, un fils qui se marie et n’a pas les moyens d’acheter un nouveau logement est obligé de demander à ses parents de céder une partie de leur boutique, ce qui donne naissance à la création des maisons tubulaires. Bien que celles-ci aient des façades très étroites, elles peuvent avoir une longueur allant jusqu’à 60 mètres.

Ce type de maison comporte généralement trois parties: le devant avec sa façade est réservé au commerce ou à l’atelier tandis qu’au milieu se trouve généralement une petite cour où on édifie une petite maison avec un dôme ressemblant à un four de 1,8 mètre de haut pour garder des objets de valeur en cas d’incendie et le derrière du magasin est destiné à l’habitation.

Dans son livre intitulé « Une description du royaume de Tonkin », le commerçant anglais Samuel Baron en a parlé avec ses illustrations et ses descriptions intéressantes.

Malgré sa taille insignifiante par rapport à celle du Vietnam, le vieux quartier de Hanoï témoigne incontestablement de la culture commerciale et urbaine des Vietnamiens au fil de plusieurs siècles. C’est un modèle dont on a besoin pour connaître d’une manière approfondie la structure traditionnelle de la « ville » dans le monde rural des Vietnamiens.

English version

Thăng Long originated from the village of Long Đỗ. As early as the 5th century, King Lý Nam Đế built here the « wooden citadel » of the kingdom of Vạn Xuân. After invading our country, the Tang dynasty took this place as the headquarters of their army on the lands of Long Đỗ and renamed it Tống Binh. Lý Công Uẩn, aided by the monk Van Hanh, discovered the enormous potential of this place because it was at the intersection of roads and waterways, facilitating the transport of goods. Moreover, it also met the balance and harmony between the elements of Water and Earth, or between the beneficial breath (Green Dragon) and the harmful breath (White Tiger) in geomancy introduced to our country by General Tang Gao Pian. Legend has it that he used spells to protect the Đại La citadel, but thanks to the help provided by the spirit « transformed into the White Horse, » Lý Thái Tổ succeeded in building the Thăng Long citadel on the old foundations of the Đại La citadel. The temple dedicated to the worship of the White Horse still exists today on Sail Street (Phố Buồm). That is why, in the autumn of 1010, Lý Thái Tổ decided to transfer the capital from Hoa Lư to the region where the dragon curled and the tiger sat. He wanted to choose a place to develop the economy long-term and foresee a bright future with prosperity and abundance for ten thousand future generations.

He then had to create artisanal factories to produce the goods that the royal court needed for consumption. There were not only talented artisans rushing to work in Thăng Long, but also farmers living in the countryside of the Red River region. The latter, during their free time, also participated in the production of handicrafts intended to be sold to intermediaries who brought them back to the capital to resell in order to make money. At first, they gathered at the four main markets located near the gates of the capital. But since the royal factories could not supply enough products, they gradually regrouped in the East Gate neighborhood because the land there was very suitable for the river transport of goods from the countryside to the capital via the Red River to Tô Lich and the canals.

At that time, in front of the market was the White Horse Temple (Bạch Mã). To its right was the Tô Lich river and a bridge, all of which today is Sugar Street (Hàng Đường). That is why in the 14th century the expression « Kẻ Chợ » (or the market people) was used to designate this lively neighborhood.It was this place that later became the district of 36 streets and guilds, intended to sell all the handcrafted products supplied by the nearby artisanal and rural villages. The shops were entirely huts used as workshops or places for trade along the street.

Similar to country houses, these shops were built of wood and bamboo, with thatched roofs and mud-plastered walls. Each house had a water jar on the roof which, in case of fire, could be overturned onto the roof to extinguish the flames. Being afraid of fire, people decided to build a temple dedicated to the fire spirit (located today on Pipe Street) to ask it not to cause any fires on the 15th day of the lunar month. Kẻ Chợ gradually escaped dependence on the capital since the 17th century under the reign of the Trinh lords thanks to a series of resolutions such as tax reduction, monetary system unification, and the completion of many urban projects leading to significant development. Artisanal merchants from the craft villages flocked to the capital to live there permanently, and foreign traders also began opening branches in the capital, making the economy more dynamic. Thanks to this, the capital had thus become the largest commercial center in northern Vietnam.

Artisans and merchants from the same village would group together into guilds and specialize collectively in production or sales within the neighborhood. To find the products you need, you just have to go to the neighborhood whose entrance gate bears a sign clearly indicating the quality and type of products sold. During this period, the word « street » was not used. According to the writer Nguyễn Ngọc Tiến, the word « street » was still used to refer to the river quay. That is why there is the phrase « Upon laying down the oar, the fisherman hurries back to the distant shore » in the poem « Afternoon tinged with nostalgia » by Mrs. Huyện Thanh Quan. According to the French historian Philippe Papin, the word « street » was used in 1851 in the districts of Thọ Xuyên and Vĩnh Thuận. That is why the position of street chief appeared in his book entitled « History of Hanoi. »

In the book entitled Đai Nam Nhất Thống Chí (Geography of Vietnam), it is written as follows: Hanoi was the ancient capital, originally comprising 36 streets, etc. In the book « A Journey to Tonkin in the Year of the Wooden Pig (1876) » by the scholar Trương Vĩnh Ký, he listed 21 streets including: Hàng Buồm (Sail Street). This street was also the street of Chinese immigrants with many traditional medicine shops and Chinese restaurants. Hàng Quảng Đông was the street of the Cantonese during the French era (today’s Hang Ngang street). Hàng Mã (Copper Street during the French era) was associated with the production and trade of votive papers, funeral objects, etc. The word « street » could therefore have originated at the beginning of King Tự Đức‘s reign.

Jewelers from the village of Châu Khê had settled in the money changers’ street (Hàng Bạc). As for the woodturners from the village of Nhi Kê, they lived on Tô Tịch street, and so on… They always maintained contact with their native village in the countryside by recruiting workers, supplying materials, registering their names in the village genealogy, and participating each year in village festivals.

The rural villages thus became places that supplied not only the urban villages with high-tech products but also agricultural products for the capital. It can be said that the countryside villages and the capital’s villages depended on each other. Thanks to this interdependence, the spirit of solidarity between urban and rural villages was even stronger. Each urban village was built along a street or a section of a street and depended on one or more villages practicing the same trade. At that time, the uniqueness of the village lay in the fact that at each end of the village there was always an entrance gate that was closed at night. Each village also had a distinct administrative body with a village chief, a communal house dedicated to the worship of the ancestors of the trade or the village spirits from which the people originated.

During the French colonial period, to prevent fires, the French government decided to reorganize the city through architectural works with tubular houses that can still be seen today in the old town of Hanoi. However, they also caused the disappearance of many ponds and lakes such as Hang Dao Lake, Ma Canh Lake, Hang Chuoi Lake, Lien Tri Lake, etc., to build houses and public buildings. In 1894, the French drained the upper part of the To Lich River to build the Dong Xuan Market. They again destroyed the walls of the Hanoi citadel and its gates. Only the Quan Chuong Gate (the East Gate) remained, and the To Lich River below the citadel was also filled with sand and sediment. Now, many streets exist only in name, such as Hang Bè Street (Raft Street), because the sand pushed the river further away, so rafts can no longer approach the foot of the embankment. Therefore, there are no more rafts. Consequently, there is no longer a raft market on the embankment.

As for the tube houses, they are seen to highlight the Western style, particularly their façade with balcony, loggia, porch, etc. The construction materials include cement, reinforcing bars, concrete, glass, etc. However, according to the French historian Philippe Papin, the tube houses of Hanoi are influenced by the Chinese community. This argument is not necessarily false if one has the opportunity to visit the old Chinese houses in Hội An. But according to the writer Nguyễn Ngoc Tiến, under the reign of King Minh Mang, the tax on shops was not based on the size or depth of the shop, but only on the façade. The owner of a shop with a relatively wide façade had to pay a higher tax compared to one with a small façade. It was advantageous to divide the large façade into several small façades, thus into several shops. Sometimes, a son who got married and could not afford to buy a new home was forced to ask his parents to give up part of their shop, which led to the creation of tube houses. Although these have very narrow façades, they can be up to 60 meters long.

This type of house generally consists of three parts: the front with its facade is reserved for commerce or the workshop, while in the middle there is usually a small courtyard where a small house with a dome resembling a 1.8-meter-high oven is built to keep valuables safe in case of fire, and the back of the shop is intended for living quarters.

In his book titled « A Description of the Kingdom of Tonkin, » the English merchant Samuel Baron spoke about it with his illustrations and interesting descriptions. Despite its insignificant size compared to that of Vietnam, the old quarter of Hanoi unquestionably bears witness to the commercial and urban culture of the Vietnamese over several centuries. It is a model needed to gain a deep understanding of the traditional structure of the « city » in the rural world of the Vietnamese.

Galerie des photos

[Return HANOÏ]

Bibliographie:

Nguyễn Bá Chính : Hà Nôi Chỉ Nam. Guide de Hanoï. Nhà xuất bản Nhã Nam, Hà Nội.

Philippe Papin : Histoire de Hanoï. Editeur Fayard.

Hữu Ngọc: Hà Nội của tôi. Nhà xuất bản Văn Học.

Nguyễn Ngọc Tiến: Làng Làng Phố Phố Hà Nội. Nhà xuất bản hội nhà văn.