Tại sao Việt Nam ta không bị đồng hóa?

Pourquoi le Vietnam n’est pas assimilé?

Why is Vietnam not assimilated?

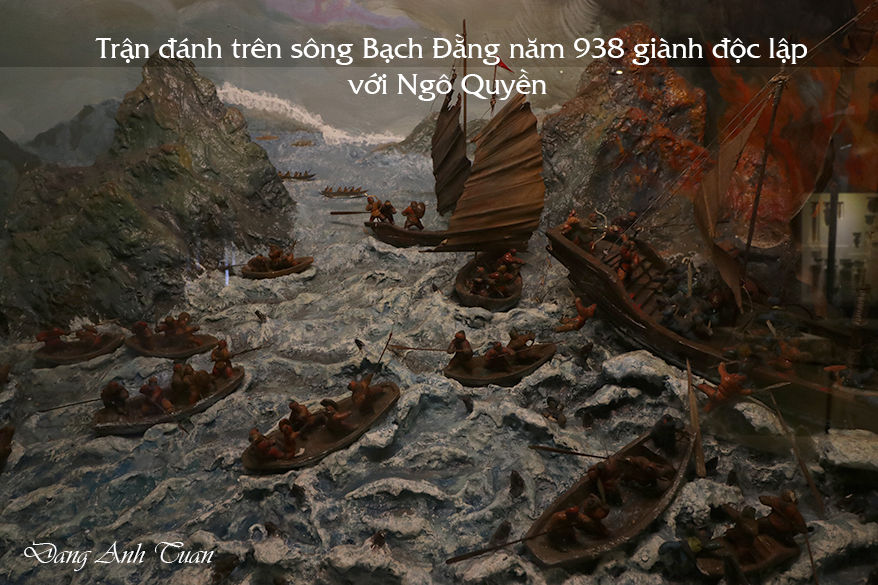

Rất hiếm có trong lịch sử loài người một nước như Việt Nam chúng ta bị thống trị bởi người Hoa có một ngàn năm mà không bị đồng hóa. Làm thế nào một dân tộc chỉ có mãnh đất « Đồng Bằng Bắc Bộ » không bị chinh phục bởi một đế chế rộng lớn “Trung Quốc” cai quản một lãnh thổ ngày nay tương đương với Âu Châu? Chúng ta cần tìm hiểu những lý lẽ nào ông cha ta đã thành công trong việc thoát khỏi sự thống trị và dành lại độc lập chớ theo nhà Hán học Christine Nguyen Tri [1], giảng viên của trường INALCO (Paris) thì Trung Quốc là một ma trận kì ảo: nó thu hút các lãnh thổ xung quanh và cư dân. Những người nầy từ lúc bước vào ma trận thì vĩnh viễn ở mãi mãi trong đó.

Dù có xâm chiếm và cai trị được Trung Hoa một thời như các dân tộc hiếu chiến Nữ Chân (nhà Liêu), Mông Cổ (nhà Nguyên) hay Mãn Châu (nhà Thanh) rồi cũng bị đồng hóa bởi người Hán. Còn ta có gì để thoát khỏi được sự Hán hóa nhất là dân tộc ta thường được xem kém cỏi về dân số chỉ vỏn vẹn một triệu người so với dân số thời vua Hán Vũ Đế (50 triệu) chưa kể nói đến lễ nghĩa còn phải học với sách vở của Khổng Phu Tử, còn lại không biết cày cấy cần nhờ các thái thú Cửu Chân thời nhà Tây Hán Tích Quan (Si Kouang) và Nhâm Diên (Ren Yan) dạy dân khai khẩn ruộng đất, hàng năm cày trồng để cho trăm họ no đủ trong Hậu Hán Thư. Thời đó những bộ tộc sống bên ngoài nền văn minh Trung Quốc như Yi, Rong, Di, Man thì được viết với bộ thủ của một con vật để nói lên sự khinh khi và miệt thị. Như vậy những dân tộc Nữ Chân, Mông Cổ hay Mãn Châu dù có sức mạnh lúc đó để thống trị nước Trung Hoa nhưng văn hóa họ kém nên bị đồng hóa.

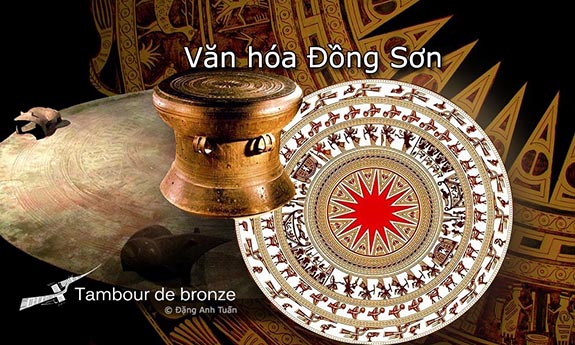

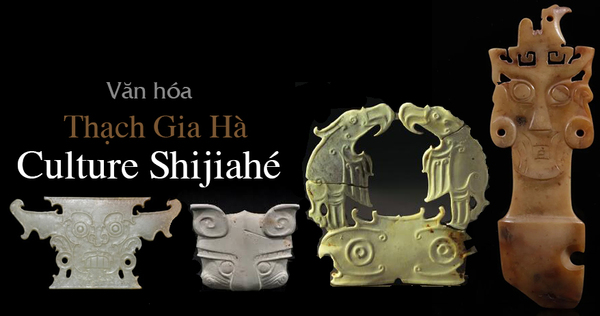

Còn ta không bị đồng hóa tức là phải có một văn hóa tương đương với nền văn hoá của họ. Điều nầy đã được rõ từ khi có các cuộc nghiên cứu di truyền trong thời gian qua. Với nghiên cứu của Huang et al. 2020 [2] thì cho thấy người Việt cổ là hậu duệ của văn hóa Đồng Sơn vì các mẫu di truyền cổ của văn hóa Đông Sơn là của người Việt hiện đại trùng lặp với nhau. Đây cũng là một văn hoá độc lập cuối cùng trước khi nước ta mất quyền tự chủ và bị rơi vào thời kỳ 1000 năm Bắc thuộc. Chính nó là văn hóa thừa kế từ văn hóa Phùng Nguyên và các văn hóa ở vùng hạ và trung lưu của sông Dương Tử (Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà) tức là văn hóa trồng lúa nước mà nhà khảo cổ Pháp Madeleine Colani khám phá ra được ở làng Hoà Bình (Việt Nam) vào năm 1922 và cho nó với cái tên Hòa Bình. Văn hóa nầy cách ngày nay 15.000 năm, kéo dài cho đến 2.000 năm trước Công Nguyên ở Đông Nam Á.

Theo tác giả Lang Linh[4] ý thức Việt có thể nói là cốt lõi của người Việt, đó chính là ý thức dân tộc, bắt đầu xuất hiện từ thời văn hóa Lương Chử ở hạ lưu sông Dương Tử, tiếp tục được tộc Việt sử dụng và kế thừa khoảng chừng 3000 năm trước Công Nguyên và bị thất bại về sau trong những cuộc chiến chống xâm lược của các triều đại Sở – Tần – Hán. Văn hóa Lương Chử là văn hóa đầu tiên hình thành nên cộng đồng tộc Việt, mà trong đó, người Việt thuộc ngữ hệ Nam Á [5] ngày nay đóng một vai trò rất quan trọng. Tên Việt được hình thành từ hình chiếc rìu rồi sau đó đến thủ lĩnh cầm rìu với ý nghĩa đại diện tộc Việt trong nghi lễ [6]. Đến thời kỳ văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà ở vùng trung lưu Dương Tử thì thấy hình ảnh thủ lĩnh đội mũ lông chim cầm rìu và sau đó hình ảnh thủ lĩnh cầm rìu xuất hiện rất phổ biến trên các trống đồng Đồng Sơn khoảng chừng 500 năm trước Công nguyên.

Văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà nằm ở trong địa bàn của nước Sở. Qua sự mô tả địa lý trong truyền thuyết thì được biết nước Văn Lang thời đó đóng đô ở Phong Châu, có đất đai rộng lớn giáp ranh bắc đến hồ Động Đình, nam giáp nước Hồ Tôn (Chiêm Thành), đông giáp biển Nam Hải, tây đến Ba Thục (Tứ Xuyên). Theo nhà Hán học Pháp Léonard Aurousseau, Văn Lang nằm trong địa bàn của nước Sở gồm có hai tỉnh Hồ Bắc (Hubei) và Hồ Nam (Hunan) thời Xuân Thu. Cư dân nước Sở thời đó có thói xăm mình, ưa ở trong nước, cắt tóc để tựa giống các cá sấu con tránh sự tấn công của các con sấu lớn theo lời tường thuật của Tư Mã Thiên trong sử ký mà được nhà khảo cổ Pháp Edouard Chavannes [7] dịch lại (ibid 216).

Hơn nữa theo Léonard Aurousseau, các lãnh tụ của người Việt cổ và nước Sở đều có tên thị tộc chung là Mị 咩(hay tiếng dê con kêu trong tiếng Hán-Nôm) như vậy họ cùng chung tổ tiên. Theo Léonard Aurousseau [8], ở thế kỷ IX trước Công Nguyên, một nhóm người của lãnh chúa phong kiến nước Sở có tên thị tộc Mị di cư dọc theo sông Dương tử và xâm chiếm vùng đất phì nhiêu ở Chiết Giang lập nên một vương quốc Việt chỉ được nói đến trong biên niên sử Trung Hoa ở vào thế thế kỷ VI trước Công Nguyên (ibid 261).Tại sao có cuộc di cư diễn ra như vậy ? Điều nầy Léonard Aurousseau không giải thích nhưng theo tác giả Lang Linh thì vua nước Sở không còn phải là ngưòi Việt mà là người Hoa được nhà Châu phong chức sau khi diệt được nhà Thương ở đất của đại tộc Bách Việt. Chính vì vậy có cuộc di cư dẫn đến sự thành hình nước Việt của Câu Tiễn ở cuối thời Xuân Thu ở bắc Chiết Giang mà trước đó không nghe nói đến trong sử Trung Hoa. Tại sao Léonard Aurousseau khẳng định tổ tiên của chúng ta cùng một gốc với nguời Việt của vương quốc Câu Tiễn? Trong sử sách của ta lúc nào cũng dùng bộ thủ Việt 越 để chỉ định người Việt, nước Việt chúng ta còn trong sử ký Trung Hoa cũng dùng bộ thủ nầy để nói đến vương quốc của Câu Tiễn.

Cũng theo Léonnard Aurousseau thì ngoài tên Lo Yue (Lạc Việt) dưới thời nhà Châu, Si ngeou (Tây Âu) hay Ngeou-Lo (Âu Lạc) dưới nhà Tần, tổ tiên của dân tộc ta cùng gốc với dân tộc Việt của Câu Tiễn ở vùng Ôn Châu (Chiết Giang). Trước hết cả hai dân tộc đều có cùng một nhánh Ngeou chung trong tộc Việt. Dân tộc ta thi được gọi là Si Ngeou (tộc Việt ở phương Tây) còn dân tộc ở Ôn Châu, Chiết Giang (Wen-tcheou, Tchô-kiang) thì Tong Ngeou (tộc Việt ở phương Đông). Nhánh Ngeou trong tộc Việt rất quan trọng để nói lên mối họ hàng thân thiết, từ nhánh đó họ xuất thân. Sau đó ông còn chứng minh rằng hai tộc Việt nhánh Ngeou nầy có những tập tục giống nhau như cắt tóc, xăm mình, khoanh tay, gài vạt áo bên tay trái vân vân (ibid 248) Tập tục khoanh tay hay thường thấy ở người Việt chúng ta để bày tỏ sự kính trọng chớ không có trong nghi lễ của người Hoa.

Dựa trên các luận điểm trên, Léonard Aurousseau khẳng định tổ tiên của ta cùng cư dân của vương quốc Việt của Câu Tiễn cùng chung một thị tộc. Nước Việt của Câu Tiển bị thôn tính bởi nước Sở vào năm 333 TCN (trước Công Nguyên) và sau đó nước Tần diệt Sở, thống nhất Trung Hoa thì có một cuộc di tản trọng đại của các tộc Việt trong đó có cả tổ tiên của chúng ta (người Kinh) quay trở về Đông Nam Á bằng cách đi vòng theo các ngọn núi ở ven bờ biển Đông từ Thái Châu (Chiết Giang) để về cư trú ở Quảng Đông, Quảng Tây và châu thổ sông Hồng.

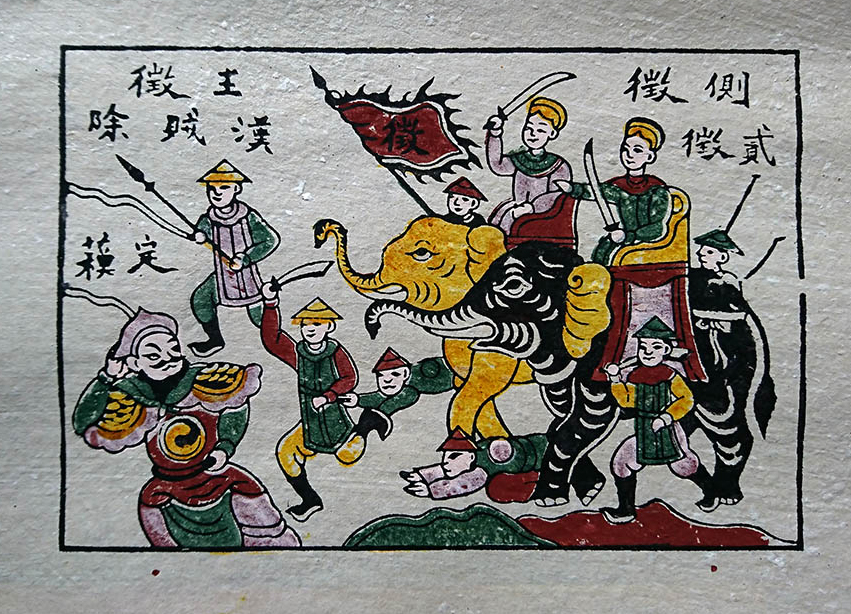

Theo sử ký thì có sự thành hình nhiều tiểu quốc tộc Việt dọc theo bờ biển Đông trong cuộc di tản nầy nên mới gọi là Bách Việt rồi từ từ các tiểu quốc nầy thôn tính lẫn nhau để thành hình các nước lớn trong đó có nước Mân Việt, Đông Âu, Tây Âu, Âu Lạc của An Dương Vương (Thục Phán) và Nam Việt của tướng Triệu Đà nhà Tần. Nói tóm lại chỉ có Quảng Đông, Quảng Tây và châu thổ sông Hồng là nơi mà các tộc Việt ngữ hệ Nam Á cùng gốc với tổ tiên của chúng ta cư ngụ dựa theo các tâp quán và các cuộc khảo cứu di truyền và ngôn ngữ còn các tộc Việt khác bị Trung Quốc đồng hóa. Bởi vậy khi có cuộc nổi dậy của hai Bà Trưng dưới thời nhà Tây Hán thì hai bà rất thành công trong việc chiếm được khoảng thời gian đầu 65 thành trì từ Lưỡng Việt (Quảng Đông, Quảng Tây ngày nay) đến Mũi nậy được 9 quận: Nam Hải, Uất Lâm, Thương Ngô, Giao Chỉ, Cửu Chân và Nhật Nam. Chính cũng các nơi nầy còn tìm thấy về sau các trống đồng mà Trung quốc nói là thuộc về họ.

Sự việc nầy nói lên các vùng nầy có một thời thuộc về tộc Việt chúng ta. Theo Leonard Aurousseau thì cư dân ở châu thổ sông Hồng thời đó tức là thời Hùng Vương gồm có Việt tộc (người Kinh và người Mường), người Tày-Thái-Nùng và người bản xứ gốc Nam Đảo. Chính nhóm gốc Nam Đảo nổi loạn về sau lập nước Lâm Ấp (Lin Yi) ở thế kỷ thứ 2 SCN (sau Công Nguyên). Chính trong nhóm Tày-Thái –Nùng có một người Tày tên là Thục Phán (Cao Bằng) lập ra nước Âu Lạc thay thế họ Hồng Bàng. Vương quốc của Thục Phán hay An Dương Vương chỉ có tồn tại 50 năm bị Triệu Đà tướng nhà Tần diệt lâp nên nước Nam Việt vào năm 207 TCN. Trong thời gian ông cai trị nước Nam Việt, ông dùng chính sách « hoà tập Bách Việt » nhằm thống nhất các bộ tộc Bách Việt và chính sách « Hoa – Việt dung hợp » nhằm đồng hoá người Hoa ở Lĩnh Nam và ở lãnh thổ nước Nam Việt.

Chính sách nầy làm các tộc Việt qui thuận và được xem như là vua nước Việt trong sử sách Việt dưới thời phong kiến chớ ông không phải là đại diện tộc Việt với các sử gia hiện nay. Chính nhờ triều đại mà ông thành lâp có được gần một trăm năm, Việt tộc của chúng ta mới có thời gian thuận lợi để định cư vĩnh viễn ở châu thổ sông Hồng. Họ không bị cuốn hút bởi khối người Hán tộc và còn tồn tại lại sau mười một thế kỷ thống trị gần như không bị gián đoạn.

Dân tộc ta rất coi trọng việc trồng lúa nước. Từ ngàn xưa, dân ta khai khẩn trồng lúa nhờ xem thủy triều lên xuống mà thu hoạch được hai lần một năm từ đất. Dân tộc ta rất gắn bó mật thiết với Đất và Nước, hai nguyên liệu cần thiết trong việc trồng lúa. Vì vậy tổ tiên ta mới dùng hai chữ Đất Nước để ám chỉ Nước, nơi mà họ sinh ra và có liên kết tình cảm sâu sắc với làng mạt. Chính đây cũng là cái nôi của dân tộc Việt, nơi gìn giữ tất cả tập quán và truyền thuyết được phổ biến ở các đền thờ cúng tổ tiên mà cũng là nơi bất khả xâm phạm được dưới thời thống trị của người phương Bắc. Phần lớn các làng Việt là của nông dân nên đều có đình, nơi thờ các thành hoàng và những người có công với làng. Các làng Việt được có những đặc quyền bên cạnh quyền lực tuyệt đối của kẻ xâm lăng và có cấu kết cộng động rất chặt chẽ như một đại gia đình. Người nông dân có quyền nói tiếng mẹ đẻ không cần học viết chữ Hán vì đâu có tiếp cận thường ngày với người Hán chỉ nhờ đến các hương chức ở trong làng. Còn nếu có học chữ Hán thì chỉ có giới tinh hoa học cần hiểu văn bản kinh thư tiếng Hán để thi cử còn nói thì vẫn dùng âm Hán Việt. Như vậy hoàn toàn không thể biến tiếng Việt thành một phương ngữ của Hán ngữ vì ta vẫn hoàn toàn nói và nghe bằng tiếng mẹ đẻ dù viết chữ Hán. Nhờ đó việc Hán hóa về ngôn ngữ trở thành vô dụng vì theo nhà nghiên cứu Nguyễn Hải Hoành [7], tiếng ta còn thì nước ta còn. Ông cha ta đã sớm nghĩ tới việc mượn thứ chữ này làm chữ viết cho dân tộc ta từ thời Sĩ Nhiếp. Mỗi chữ Hán đều có một âm tiếng Hán, muốn học chữ Hán tất phải đọc được âm của nó. Mỗi chữ Hán đều được đặt cho một (hoặc vài) cái tên tiếng Việt xác định, gọi là từ Hán-Việt.Thứ chữ Hán đọc bằng âm Hán-Việt này được dân ta gọi là chữ Nho. Chỉ cần học mặt chữ, nghĩa chữ và cách viết văn chữ Hán mà không cần học phát âm cũng như học nghe/nói tiếng Hán.

Theo nhà nghiên cứu Pháp Bernard Philippe Groslier (CNRS) [9], làng Việt xem như là một tế bào được nuôi dưởng trong mỗi lô đất của đồng bằng phù hợp với phương pháp canh tác mà nó còn là một hộ gia đình độc lập về chính trị và đồng nhất về mặt xã hội khiến nó trở thành một công cụ hiệu quả chống ngoại xâm và bành trướng lãnh thổ. Như vậy làng ta có sức sống mãnh liệt mà cũng là sức mạnh cho sự bành trướng không thể tưởng tượng trong cuộc hành trình về phương nam. (Chiêm Thành và Chân Lập).

Chính nhà Đông Phương học Pháp Paul Mus [10] cũng đã nhận thấy ra điều nầy nên ông mới viết như sau: Việt Nam là xã hội làng mạc. Làng là « yếu tố cơ bản » vì nó đã « xây dựng » quốc gia Việt Nam (ibid.: 329). Làng là « thành trì của cuộc kháng chiến thắng lợi chống Trung Quốc » (ibid.: 279) và rộng hơn, nó là lò nung đốt của « tính không phân nhường quốc gia » để chống lại « các cuộc chia rẻ và chinh phục » (ibid.: 19). Người Hán chỉ nắm quyền đến cấp huyện còn làng xã ta do người Việt đứng đầu quản lý. Có lẽ người Hán quá tự tin họ nhất là họ đồng hóa dễ dàng dân Bách Việt phía Nam sông Dương Tử nên họ nghĩ có thể đồng hóa tổ tiên của chúng ta (Âu Lạc) như vậy. Chắc hẳn người Hán dựa lên câu nói của nhà triết gia Mạnh Tử của họ như sau: Tôi đã nghe nói về những người sử dụng học thuyết của đất nước chúng ta để thay đổi những kẻ man rợ, nhưng tôi chưa bao giờ nghe nói về những người chúng ta bị những kẻ man rợ thay đổi. Chính vì họ không thấu hiểu người Việt chúng ta nên mới có sự khinh khi miệt thị. Có một thời họ còn gọi dân ta là những người đi chân trần chớ đâu có biết rất tiện leo cây và suốt ngày tay lấm chân bùn trong nước cho việc trồng lúa. Họ quên rằng dân tộc ta xuất thân từ hạ lưu sông Dương Tử với văn hóa Lương Chử, một văn hóa tương đương với văn hóa họ có 3000 năm TCN di tản chịu nhiều gian khổ để định cư cuối cùng ở đồng bằng sông Hồng qua nhiều thế kỷ. Họ quên rằng dân tộc ta là dân tộc có sức sống mãnh liệt và một tộc còn lại duy nhất gồm tựu lại tất cả thành phần ưu tú của các tộc Việt trong đại tộc Bách Việt không bị họ Hán hóa và không chịu qui phục trước bạo lực dù bị họ thống trị suốt một ngàn năm. Họ quên rằng dân tộc ta thà mất đất chớ lúc nào cũng muốn thoát ảnh hưởng họ nên trong bộ thủ « Việt » của tự điển Hán-Nôm về sau có thêm ý nghĩa « thoát » và dùng chử Hán để phổ biến tiếng nôm của ta một cách tuyệt vời. Họ quên rằng làng xã của dân ta là một thành trì kiên cố bất khả xâm phạm không những để chống họ mà còn là một công cụ bành trướng hữu hiệu trong cuộc hành trình về phương nam. Làm sao có thể không hiểu thâm ý của họ một khi thông hiểu tường tận binh thư Tôn Tử của họ trong suốt thời gian bị đô hộ.

Lấy lại câu nói kết luận của Léonard Aurousseau, sau hai mươi hai thế kỷ đấu tranh, người dân Việt dừng lại, nhận thức mình đã tôn vinh những nỗ lực ban đầu của tổ tiên từ bờ biển Đông và đã mãn nguyện có được môt quê hương dường như điều mong muốn nó phù hợp với trí tuệ của giống nòi.

Il est très rare dans l’histoire de l’humanité qu’un pays comme le Vietnam ait été dominé par les Chinois pendant mille ans sans être assimilé. Comment une nation ne possédant qu’une portion de territoire appelée « Delta du Tonkin » aurait- elle pu ne pas être conquise par un vaste empire appelé la « Chine » qui régnait sur un territoire aujourd’hui équivalent à l’Europe ? Il est nécessaire de comprendre les raisons qui ont poussé nos ancêtres à échapper à la domination et à retrouver leur indépendance, car selon la sinologue Christine Nguyen Tri [1], maître de conférences à l’INALCO (Paris), la Chine est une matrice magique : elle attire les territoires et leurs habitants. Ces derniers, dès leur entrée dans la matrice, y demeurent à jamais.

Bien qu’ils aient réussi à envahir et gouverner la Chine durant une période comparable à celle des guerriers Jurchen (dynastie Liao), des Mongols (dynastie Yuan) ou des Mandchous (dynastie Qing), ils étaient néanmoins assimilés par les Han. Comment pouvons-nous faire pour échapper à la sinisation, surtout quand notre peuple est souvent considéré comme inférieur, seulement un million d’habitants comparés à la population de l’empereur Wu Di des Han (50 millions) en termes de population, sans compter que nous devons encore apprendre les bonnes manières dans les livres de Confucius, et que nous ne savons ni labourer ni cultiver les champs de riz? Nous avons donc besoin de l’aide des préfets de Cửu Chân sous la dynastie des Han occidentaux, Si Kouang et Ren Yan, qui ont appris à notre population à mettre en valeur la terre, à la labourer et à la cultiver chaque année pour subvenir aux besoins de la population selon le Livre des Han postérieurs. À cette époque, les tribus vivant en dehors de la civilisation chinoise, comme les Yi, Rong, Di et Man, étaient désignées par les Han à l’aide du radical d’un animal pour exprimer leur mépris et leur dédain. Ainsi, les Jurchens, les Mongols et les Mandchous, malgré leur pouvoir de dominer la Chine à cette époque, avaient une culture inférieure et ils étaient donc assimilés.

Si nous ne sommes pas assimilés, nous devons avoir une culture équivalente à la leur. Cela est clairement apparu depuis des études génétiques récentes. Selon les recherches de Huang et al. 2020 [2], il est démontré que les anciens Vietnamiens sont les descendants de la culture Dong Son, car les anciens échantillons génétiques de cette culture sont ceux du peuple vietnamien moderne. Il s’agit également de la dernière culture indépendante avant que notre pays perde son autonomie et tombe dans une période de 1 000 ans sous la domination chinoise. Il s’agit de la culture héritée de la culture de Phùng Nguyên et des cultures des cours inférieur et moyen du fleuve Yangtsé (Lianzhu et Shijiahé), c’est-à-dire la culture du riz inondé que l’archéologue française Madeleine Colani a découverte dans le village de Hoa Bình (Vietnam) en 1922 et lui a donné le même nom. Cette culture vieille de 15 000 ans a perduré jusqu’à 2 000 ans avant J.-C. en Asie du Sud-Est.

Selon l’auteur Lang Linh [4], la conscience Yue (Việt) peut être considérée comme le noyau du peuple Yue (Việt), c’est-à-dire la conscience nationale apparue à partir de la culture de Liangzhu dans le cours inférieur du fleuve Yangtsé, a continué à être utilisée et héritée par le peuple Yue (Việt) environ 3000 ans avant J.-C. et a été vaincue plus tard dans les guerres contre l’invasion des dynasties Chu-Qin-Han. La culture de Liangzhu a été la première culture à former la communauté ethnique Yue (Việt), dans laquelle le Proto-Vietnamien appartenant à la famille linguistique sud-asiatique [5] jouait à cette époque un rôle très important. Le nom Yue (Việt) a été formé à partir de l’image d’une hache, puis celle d’un chef tenant la hache dans le but de représenter le peuple Yue (ou Việt) dans les rituels [6]. Pendant la période de la culture Shijiahé dans le moyen fleuve Yangtsé, l’image du chef portant un chapeau de plumes tenant une hache était apparue très couramment sur les tambours en bronze de Dong Son environ 500 ans.

La culture de Shijiahé était située sur le territoire de l’État de Chu. La description géographique de la légende indique que l’État de Văn Lang avait alors sa capitale à Phong Châu, avec une zone très vaste bordant le lac Dongting au nord, Hồ Tôn (Champa) au sud, la mer de Chine méridionale à l’est et Ba Thục (Sichuan) à l’ouest. Selon le sinologue français Léonard Aurousseau, Văn Lang était située sur le territoire de l’État de Chu, comprenant en gros les deux provinces du Hubei et du Hunan pendant la période des Printemps et Automnes. Les habitants de l’État de Chu avaient alors l’habitude de se tatouer, de rester dans l’eau, et de se couper les cheveux pour ressembler à des petits crocodiles afin d’éviter les attaques des grands crocodiles, selon les archives historiques de Sima Qian, traduites par l’archéologue français Édouard Chavannes [7] (ibid. 216).

De plus, selon Léonard Aurousseau, les dirigeants de l’ancien Vietnam et de l’État Chu portaient tous le même nom de clan, Mị 咩 (ou le bêlement du mouton en sino-nôm), partageant ainsi les mêmes ancêtres. Selon Léonard Aurousseau [8], au IXème siècle avant J.-C., un groupe important de gens issus de l’État Chu portant le nom de clan Mị migra le long du fleuve Yangtze et envahit les terres fertiles du Zhejiang, établissant un royaume Yue (Việt) qui n’était mentionné dans les chroniques chinoises qu’au VIème siècle avant J.-C. (ibid. 261). Pourquoi cette migration a-t-elle eu lieu ? Léonard Aurousseau n’a pas donné l’explication mais d’après l’auteur Lang Linh, l’état Chu était gouverné désormais par un roi chinois nommé par la dynastie des Chou (Nhà Châu) sur le territoire des Bai Yue après avoir éliminé la dynastie des Shang, ce qui expliquait la naissance du royaume Yue de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) à la fin de la période des Printemps et Automnes dans le nord du Zhejiang. Ce royaume n’avait jamais été mentionné auparavant dans l’histoire chinoise. Pourquoi Léonard Rousseau a-t-il affirmé que nos ancêtres avaient la même origine que le peuple Yue du royaume de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) ? Dans nos livres d’histoire, le radical Viet 越 est toujours utilisé pour désigner le peuple vietnamien, notre pays Viet, et dans les livres d’histoire chinois, ce radical est également utilisé pour désigner le royaume de Goujian (Câu Tiễn).

Selon Léonard Aurousseau, outre le nom Lo Yue (Lạc Việt) sous la dynastie Zhou, Si ngeou (Tây Âu) ou Ngeou-Lo (Âu Lạc) sous la dynastie Qin, les ancêtres de notre peuple ont la même origine que le peuple Yue de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) dans la région de Wenzhou (Ôn Châu)(Zhejiang). Tout d’abord, les deux peuples ont la même branche commune Ngeou au sein du peuple Yue(Việt). Notre peuple est appelé Si Ngeou (peuple Yue de l’Ouest) tandis que les habitants de Wenzhou, Zhejiang (Wen-tcheou, Tchô-kiang) sont appelés Tong Ngeou (peuple Yue de l’Est). La branche Ngeou au sein du peuple Yue (Việt) est très importante pour montrer la parenté étroite dont ils sont issus. Il a ensuite prouvé que les deux groupes ethniques Yue (Việt) de la branche Ngeou avaient des coutumes similaires telles que se couper les cheveux, se tatouer, croiser les bras, mettre le pan de chemise sur le bras gauche, etc. (ibid 248). La coutume de croiser les bras est souvent observée chez les Vietnamiens pour montrer du respect, mais elle ne se retrouve pas dans les rituels chinois.

En s’appuyant sur ces arguments, Léonnard Aurousseau affirmait que nos ancêtres et les habitants du royaume Yue de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) appartenaient au même clan. Le royaume Yue de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) fut annexé par le royaume Chu (Sờ) en 333 av. J.-C. (avant notre ère), puis le royaume Qin détruisit Chu et unifia la Chine. Il y eut une importante migration des ethnies Yue, dont nos ancêtres (les Kinh), retournant en Asie du Sud-Est en contournant les montagnes de la côte est depuis Taizhou (Thái Châu (Zhejiang) pour s’installer dans le Guangdong, le Guangxi et le delta du fleuve Rouge.

Selon les archives historiques, de nombreuses petites nations Yue se formèrent le long de la côte de la mer de l’Est lors de cette migration, d’où leur nom de Bai Yue (Bách Việt). Ces petites nations s’annexèrent ensuite progressivement pour donner naissance à des royaumes, dont Man Yue, Đông Âu, Tây Âu, Âu Lạc d’An Dương Vương (Thục Phán) et Nam Việt (Nan Yue) du général Zhao To de la dynastie Qin. En résumé, seuls Guangdong, Guangxi et le delta du fleuve Rouge abritaient des groupes ethniques Yue de même origine que nos ancêtres, d’après les coutumes et les recherches génétiques et linguistiques, tandis que d’autres groupes ethniques Yue étaient assimilés par la Chine. Ainsi, lors du soulèvement des deux sœurs Trưng sous la dynastie des Han occidentaux, elles réussirent à s’emparer avec succès des 65 premières citadelles de Lưỡng Việt (aujourd’hui Guangdong et Guangxi) jusqu’à Mũi Này, conquérant ainsi 9 districts : Nam Hải, Uất Lâm, Thượng Ngô, Giao Chi, Cửu Chân et Nhật Nam. C’est également à ces endroits que furent découverts plus tard des tambours de bronze que les Chinois prétendaient leur appartenir. Ce fait prouve que ces zones appartenaient autrefois à notre peuple vietnamien.

Selon Léonard Aurousseau, les habitants du delta du fleuve Rouge comprenaient à l’époque du roi Hùng les Proto-Vietnamiens (peuples Kinh et Mường), les peuples Tày-Thái-Nùng et les peuples autochtones d’origine austronésienne. Ce sont ces derniers austronésiens qui établirent plus tard le royaume de Lâm Ấp (Lin Yi) au IIème siècle après J.-C lors de leur révolte. C’est dans le groupe Tày-Thái-Nùng qu’il y avait un Tày nommé Thục Phán (Cao Bằng) qui réussit à fonder le royaume Au Lac pour remplacer le royaume Văn Lang de la dynastie des Hồng Bàng. Le royaume de Thục Phán (ou An Dương Vương) ne dura que 50 ans et il fut détruit par Triệu Đà (Zhao To), un général de la dynastie des Qin et le fondateur du royaume de Nan Yue en 207 avant J.C. Durant son règne, il a adopté une politique de réconciliation de toutes les tribus Yue et il a mené en même temps une autre politique de « fusion Han-Yue » dans le but d’assimiler tous les Han vivant à Lingnan et dans le territoire de son royaume. Cette politique a réussi à obtenir la soumission de tous les Yue et lui a permis d’être considéré comme le roi du Vietnam dans les livres d’histoire vietnamiens à l’époque féodale mais par contre il n’était pas un représentant légal du peuple vietnamien pour les historiens actuels. C’est grâce à la dynastie qu’il a fondée durant près de cent ans que notre peuple vietnamien a eu la durée propice à l’installation définitive dans le delta du fleuve Rouge. Il n’a pas été absorbé par les Han malgré leur nombre important et a réussi à survivre durant onze siècles de domination presque ininterrompue.

Notre peuple attachait une grande importance à la riziculture inondée. Depuis l’Antiquité, notre peuple cultivait le riz en observant le flux et le reflux des marées, ce qui lui permettait de récolter deux fois par an. Il était profondément attaché à la Terre et à l’Eau, deux ingrédients essentiels à la riziculture. C’est pourquoi nos ancêtres utilisaient les deux mots « Terre » et « Eau » pour désigner leur pays, leur lieu de naissance et montrer le profond attachement à leur village. Ce dernier était aussi le berceau du peuple vietnamien, où étaient préservées toutes les coutumes et les légendes orales dans les temples ancestraux et un lieu inviolable sous la domination des gens du Nord. La plupart des villages vietnamiens appartenaient à des agriculteurs ; ils possédaient donc tous des maisons communales où étaient vénérés les génies tutélaires et les gens ayant eu le mérite de contribuer à leur développement. Les villages vietnamiens bénéficiaient des privilèges particuliers, malgré le pouvoir absolu des envahisseurs, et possédaient une structure communautaire très soudée comme une grande famille.

Les agriculteurs avaient le droit de parler leur langue maternelle sans apprendre à écrire les caractères chinois, car ils n’étaient pas en contact quotidien avec les Han et dépendaient uniquement des responsables locaux du village. L’étude des caractères chinois était réservée seulement pour l’élite qui avait besoin de comprendre les Classiques chinois pour les examens. À part cela, on continuait à parler et à écouter avec la langue vietnamienne. Il est donc absolument impossible de transformer le vietnamien en dialecte chinois, car nous parlons et nous écoutons toujours dans notre langue maternelle, même si nous écrivons les caractères chinois. Par conséquent, la sinisation de la langue devient inutile, car selon le chercheur Nguyen Hai Hoanh [7], tant que notre langue continue à être parlée et écoutée, notre pays continue à exister. Nos ancêtres avaient envisagé d’emprunter ce type d’écriture chinoise comme système d’écriture pour notre peuple depuis l’époque de Shi Xie. Chaque caractère chinois a une sonorité chinoise. Pour apprendre les caractères chinois, il faut savoir les lire. Chaque caractère chinois porte un ou plusieurs noms vietnamiens spécifiques, appelés des mots sino-vietnamiens. Ce type de caractère chinois lu avec une prononciation sino-vietnamienne est appelé « caractère Nho » par notre peuple. Il suffit de mémoriser les caractères chinois, leur signification et savoir les écrire correctement sans avoir besoin d’apprendre la prononciation en chinois.

Selon le chercheur français Bernard Philippe Groslier (CNRS) [9], le village vietnamien est considéré comme une cellule cultivée dans chaque parcelle du delta selon le mode d’agriculture, mais c’est aussi un foyer politiquement indépendant et socialement homogène, ce qui devient en fait un instrument efficace contre l’invasion étrangère et l’expansion territoriale. Ainsi, notre village possède une forte vitalité et constitue également la force d’une expansion inimaginable lors de la migration vers le sud. (Champa et Chenla).

L’orientaliste français Paul Mus [10] l’a également compris, et il a écrit : « Le Vietnam est une société des villages. Le village est l’« élément fondamental » car il a « construit » la nation vietnamienne (ibid. : 329). Le village est « la citadelle de la résistance victorieuse contre la Chine » (ibid. : 279) et, plus largement, il est le creuset de « l’indivisibilité nationale » pour lutter contre « la division et la conquête » (ibid. : 19). Les Han ne détenaient le pouvoir qu’au niveau du district, tandis que nos villages étaient gérés par les Vietnamiens. Peut-être les Han étaient-ils trop confiants dans leur capacité d’assimiler facilement le peuple Bai Yue au sud du fleuve Yangtsé, et pensaient-ils à pouvoir assimiler ainsi nos ancêtres (Âu Lac)?

Les Han devaient se fier à la parole de leur philosophe Mencius : « J’ai entendu parler de ceux qui ont utilisé les doctrines de notre pays pour changer les barbares, mais je n’ai jamais entendu dire que notre peuple ait été changé par les barbares. C’est parce qu’ils ne nous comprennent pas, nous les Vietnamiens, qu’ils nous méprisent.» Il y avait un temps où ils nous traitaient comme des gens aux « pieds nus » car ils ignoraient qu’il était très pratique de grimper aux arbres et de passer toute la journée avec les mains sales et les pieds remplis de boue dans l’eau pour cultiver du riz. Ils ont oublié que notre peuple était originaire du cours inférieur du Yangtsé, avec la culture de Liangzhu, une culture équivalente à celle qu’ils avaient eue 3 000 ans avant J.-C. et migrait au travers de nombreuses épreuves pour s’installer finalement dans le delta du fleuve Rouge au fil des siècles. Ils ont oublié que notre peuple était un peuple doté d’une forte vitalité inébranlable, le seul peuple restant formé de toutes les élites des groupes ethniques de Bai Yue qui n’a pas été sinisé par eux et qui n’a pas cédé à la violence malgré leur domination millénaire. Ils ont oublié que notre peuple préférait de perdre ses terres et vouloir échapper à leur influence. C’est pourquoi, plus tard, dans le radical « Việt » du dictionnaire Hán-Nôm on voit apparaître le sens du mot« fuir (Thoát) ». Grâce aux caractères chinois, notre langue Nôm était diffusée de manière remarquable. Ils ont oublié que nos villages étaient une forteresse imprenable, non seulement pour les combattre, mais aussi un puissant instrument d’expansion vers le sud. Comment ne pas comprendre leur mauvaise intention après avoir parfaitement appris le livre de guerre de Sun Tzu durant la période de leur domination ?

En reprenant la conclusion de Léonard Aurousseau, après vingt deux siècles de lutte, les Vietnamiens s’arrêtent et sont conscients d’avoir fait honneur aux premiers efforts de leurs ancêtres du littoral de la mer de l’Est et satisfaits d’avoir crée une patrie qui semblait faite à souhait pour le génie de leur race.

It is very rare in human history that a country like Vietnam was dominated by the Chinese for a thousand years without being assimilated. How could a nation possessing only a portion of territory called the « Red River Delta » have not been conquered by a vast empire called « China, » which ruled over a territory today equivalent to Europe? It is necessary to understand the reasons that led our ancestors to escape domination and regain their independence, because according to sinologist Christine Nguyen Tri [1], lecturer at INALCO (Paris), China is a magical matrix: it attracts territories and their inhabitants. The latter, once they enter the matrix, remain there forever.

Although they succeeded in invading and governing China for a period comparable to that of the Jurchen warriors (Liao dynasty), the Mongols (Yuan dynasty), or the Manchus (Qing dynasty), they were nevertheless assimilated by the Han. How can we escape sinicization, especially when our people are often considered inferior, only one million inhabitants compared to the population of Emperor Wu Di of the Han (50 million) in terms of population, not to mention that we still have to learn proper manners from Confucius‘s books, and that we neither know how to plow nor cultivate rice fields? We therefore need the help of the prefects of Cửu Chân under the Western Han dynasty, Si Kuang and Ren Yan, who taught our people to cultivate the land, to plow it and farm it each year to meet the needs of the population according to the Book of Later Han. At that time, tribes living outside Chinese civilization, such as the Yi, Rong, Di, and Man, were designated by the Han using the radical of an animal to express their contempt and disdain. Thus, the Jurchens, Mongols, and Manchus, despite their power to dominate China at that time, had an inferior culture and were therefore assimilated.

If we are not assimilated, we must have a culture equivalent to theirs. This has become clear from recent genetic studies. According to the research of Huang et al. 2020 [2], it is demonstrated that the ancient Vietnamese are descendants of the Dong Son culture, as the ancient genetic samples from this culture are those of the modern Vietnamese people. This is also the last independent culture before our country lost its autonomy and fell into a period of 1,000 years under Chinese domination. It is the culture inherited from the Phùng Nguyên culture and the cultures of the lower and middle courses of the Yangtze River (Lianzhu and Shijiahé), that is, the wet rice culture that the French archaeologist Madeleine Colani discovered in the village of Hoa Bình (Vietnam) in 1922 and gave the same name. This culture, 15,000 years old, lasted until 2,000 BC in Southeast Asia.

According to the author Lang Linh [4], the Yue (Việt) consciousness can be considered as the core of the Yue (Việt) people, that is, the national consciousness that emerged from the Liangzhu culture in the lower Yangtze River basin, continued to be used and inherited by the Yue (Việt) people around 3000 BC, and was later defeated in the wars against the invasion of the Chu-Qin-Han dynasties. The Liangzhu culture was the first culture to form the Yue (Việt) ethnic community, in which Proto-Vietnamese belonging to the Austroasiatic language family [5] played a very important role at that time. The name Yue (Việt) was formed from the image of an axe, then that of a chief holding the axe in order to represent the Yue (or Việt) people in rituals [6]. During the Shijiahé culture period in the middle Yangtze River, the image of a chief wearing a feathered hat holding an axe commonly appeared on Dong Son bronze drums about 500 years ago.

The Shijiahé culture was located in the territory of the State of Chu. The geographical description of the legend indicates that the State of Văn Lang then had its capital at Phong Châu, with a very vast area bordering Dongting Lake to the north, Hồ Tôn (Champa) to the south, the South China Sea to the east, and Ba Thục (Sichuan) to the west. According to the French sinologist Léonard Aurousseau, Văn Lang was located in the territory of the State of Chu, roughly comprising the two provinces of Hubei and Hunan during the Spring and Autumn period. The inhabitants of the State of Chu were then accustomed to tattooing themselves, staying in the water, and cutting their hair to resemble small crocodiles in order to avoid attacks from large crocodiles, according to the historical records of Sima Qian, translated by the French archaeologist Édouard Chavannes [7] (ibid. 216).

Moreover, according to Léonard Aurousseau, the leaders of the former Vietnam and the Chu State all bore the same clan name, Mị 咩 (or the bleating of the sheep in Sino-Nôm), thus sharing the same ancestors. According to Léonard Aurousseau [8], in the 9th century BC, a significant group of people from the Chu State bearing the clan name Mị migrated along the Yangtze River and invaded the fertile lands of Zhejiang, establishing a Yue (Việt) kingdom that was only mentioned in Chinese chronicles in the 6th century BC (ibid. 261). Why did this migration take place? Léonard Aurousseau did not provide an explanation, but according to the author Lang Linh, the Chu state was then governed by a Chinese king appointed by the Zhou dynasty (Nhà Châu) over the territory of the Bai Yue after having eliminated the Shang dynasty, which explained the birth of the Yue kingdom of Goujian (Câu Tiễn) at the end of the Spring and Autumn period in northern Zhejiang. This kingdom had never been mentioned before in Chinese history. Why did Léonard Rousseau assert that our ancestors had the same origin as the Yue people of the kingdom of Goujian (Câu Tiễn)? In our history books, the Viet 越 radical is always used to designate the Vietnamese people, our country Viet, and in Chinese history books, this radical is also used to designate the kingdom of Goujian (Câu Tiễn).

According to Léonard Aurousseau, besides the name Lo Yue (Lạc Việt) under the Zhou dynasty, Si ngeou (Tây Âu) or Ngeou-Lo (Âu Lạc) under the Qin dynasty, the ancestors of our people share the same origin as the Yue people of Goujian (Câu Tiễn) in the Wenzhou region (Ôn Châu) (Zhejiang). First of all, the two peoples have the same common branch Ngeou within the Yue (Việt) people. Our people are called Si Ngeou (Western Yue people) while the inhabitants of Wenzhou, Zhejiang (Wen-tcheou, Tchô-kiang) are called Tong Ngeou (Eastern Yue people). The Ngeou branch within the Yue (Việt) people is very important to show the close kinship from which they originate. He then proved that the two Yue (Việt) ethnic groups of the Ngeou branch had similar customs such as cutting hair, tattooing, crossing arms, placing the shirt flap on the left arm, etc. (ibid 248). The custom of crossing the arms is often observed among Vietnamese to show respect, but it is not found in Chinese rituals.

Relying on these arguments, Léonnard Aurousseau claimed that our ancestors and the inhabitants of the Yue kingdom of Goujian (Câu Tiễn) belonged to the same clan. The Yue kingdom of Goujian (Câu Tiễn) was annexed by the Chu kingdom (Sờ) in 333 BC (before our era), then the Qin kingdom destroyed Chu and unified China. There was a significant migration of the Yue ethnic groups, including our ancestors (the Kinh), returning to Southeast Asia by bypassing the mountains on the east coast from Taizhou (Thái Châu (Zhejiang)) to settle in Guangdong, Guangxi, and the Red River Delta.

According to historical records, many small Yue nations formed along the coast of the East Sea during this migration, hence their name Bai Yue (Bách Việt). These small nations gradually annexed each other to give rise to kingdoms, including Man Yue, Đông Âu, Tây Âu, Âu Lạc of An Dương Vương (Thục Phán), and Nam Việt (Nan Yue) of General Zhao To of the Qin dynasty. In summary, only Guangdong, Guangxi, and the Red River Delta housed Yue ethnic groups of the same origin as our ancestors, according to customs and genetic and linguistic research, while other Yue ethnic groups were assimilated by China.

Thus, during the uprising of the two Trưng sisters under the Western Han dynasty, they successfully captured the first 65 citadels of Lưỡng Việt (present-day Guangdong and Guangxi) up to Mũi Này, conquering 9 districts: Nam Hải, Uất Lâm, Thượng Ngô, Giao Chi, Cửu Chân, and Nhật Nam. It was also in these places that bronze drums were later discovered, which the Chinese claimed belonged to them. This fact proves that these areas once belonged to our Vietnamese people.

According to Léonard Aurousseau, the inhabitants of the Red River delta during the time of King Hùng included the Proto-Vietnemese (Kinh and Mường peoples), the Tày-Thái-Nùng peoples, and the indigenous peoples of Austronesian origin. It was these Austronesians who later established the kingdom of Lâm Ấp (Lin Yi) in the 2nd century AD during their revolt. Within the Tày-Thái-Nùng group, there was a Tày named Thục Phán (Cao Bằng) who succeeded in founding the kingdom of Âu Lạc to replace the Văn Lang kingdom of the Hồng Bàng dynasty. The kingdom of Thục Phán (or An Dương Vương) lasted only 50 years and was destroyed by Triệu Đà (Zhao To), a general of the Qin dynasty and the founder of the kingdom of Nam Việt in 207 BC.

During his reign, he adopted a policy of reconciliation of all the Yue tribes and simultaneously pursued another policy of « Han-Yue fusion » with the aim of assimilating all the Han living in Lingnan and in the territory of his kingdom. This policy succeeded in obtaining the submission of all the Yue and allowed him to be considered the king of Vietnam in Vietnamese historical books during the feudal era, but on the other hand, he was not a legal representative of the Vietnamese people for current historians. It is thanks to the dynasty he founded that lasted nearly a hundred years that our Vietnamese people had the favorable time to settle permanently in the Red River Delta. They were not absorbed by the Han despite their large numbers and managed to survive eleven centuries of almost uninterrupted domination.

Our people placed great importance on flooded rice cultivation. Since ancient times, our people cultivated rice by observing the ebb and flow of the tides, which allowed them to harvest twice a year. They were deeply attached to the Earth and Water, two essential ingredients for rice cultivation. That is why our ancestors used the two words « Earth » and « Water » to designate their country, their birthplace, and to show their deep attachment to their village. The latter was also the cradle of the Vietnamese people, where all customs and oral legends were preserved in ancestral temples and considered an inviolable place under the domination of the northern people. Most Vietnamese villages belonged to farmers; therefore, they all had communal houses where tutelary spirits and people who had contributed to their development were venerated. Vietnamese villages enjoyed special privileges despite the absolute power of the invaders and had a very close-knit community structure like a large family.

Farmers had the right to speak their mother tongue without learning to write Chinese characters, as they were not in daily contact with the Han and depended solely on the local village officials. The study of Chinese characters was reserved only for the elite who needed to understand the Chinese Classics for exams. Apart from that, people continued to speak and listen in the Vietnamese language. It is therefore absolutely impossible to transform Vietnamese into a Chinese dialect, because we still speak and listen in our mother tongue, even if we write Chinese characters. Consequently, the sinicization of the language becomes unnecessary, because according to researcher Nguyen Hai Hoanh [7], as long as our language continues to be spoken and listened to, our country continues to exist. Our ancestors had considered borrowing this type of Chinese writing as a writing system for our people since the time of Shi Xie. Each Chinese character has a Chinese sound. To learn Chinese characters, one must know how to read them. Each Chinese character carries one or more specific Vietnamese names, called Sino-Vietnamese words. This type of Chinese character read with a Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation is called « Nho characters » by our people. It is enough to memorize the Chinese characters, their meaning, and know how to write them correctly without needing to learn the pronunciation in Chinese.

According to the French researcher Bernard Philippe Groslier (CNRS) [9], the Vietnamese village is considered as a cultivated cell in each plot of the delta according to the mode of agriculture, but it is also a politically independent and socially homogeneous household, which in fact becomes an effective instrument against foreign invasion and territorial expansion. Thus, our village possesses strong vitality and also constitutes the force of an unimaginable expansion during the migration to the south. (Champa and Chenla).

The French orientalist Paul Mus [10] also understood this, and he wrote: « Vietnam is a society of villages. The village is the ‘fundamental element’ because it ‘built’ the Vietnamese nation (ibid.: 329). The village is ‘the citadel of victorious resistance against China’ (ibid.: 279) and, more broadly, it is the crucible of ‘national indivisibility’ to fight against ‘division and conquest’ (ibid.: 19). The Han held power only at the district level, while our villages were managed by the Vietnamese. Perhaps the Han were too confident in their ability to easily assimilate the Bai Yue people south of the Yangtze River, and thought they could thus assimilate our ancestors (Âu Lac)? »

The Han had to rely on the words of their philosopher Mencius: « I have heard of those who used the doctrines of our country to change the barbarians, but I have never heard that our people were changed by the barbarians. It is because they do not understand us, the Vietnamese, that they despise us. » There was a time when they treated us as « barefoot people » because they ignored that it was very practical to climb trees and spend the whole day with dirty hands and feet covered in mud in the water to cultivate rice. They forgot that our people originated from the lower course of the Yangtze River, with the Liangzhu culture, a culture equivalent to the one they had 3,000 years before Christ, and migrated through many trials to finally settle in the Red River delta over the centuries. They forgot that our people were a people endowed with a strong, unshakable vitality, the only people formed from all the elites of the Bai Yue ethnic groups who were not sinicized by them and who did not yield to violence despite their millennial domination. They forgot that our people preferred to lose their lands rather than submit to their influence. That is why, later, in the radical « Việt » of the Hán-Nôm dictionary, the meaning of the word « to flee (Thoát) » appears. Thanks to Chinese characters, our Nôm language was remarkably disseminated. They forgot that our villages were an impregnable fortress, not only to fight them but also a powerful instrument for expansion towards the south. How can one not understand their ill intentions after having thoroughly studied Sun Tzu’s Art of War during their period of domination?.

Summing up Léonard Aurousseau’s conclusion, after twenty-two centuries of struggle, the Vietnamese pause and are aware that they have honored the initial efforts of their ancestors from the coast of the East Sea and are satisfied with having created a homeland that seemed perfectly suited to the genius of their race.

Paris ngày 7/5/2025

Tài liệu tham khào :

[1] Christine Nguyễn Tri: La conquête de l’espace chinois sous les Qin et les Han 221 avant notre ère. Cahiers CEHD, n°34

[2] Huang, X., Xia, Z., Bin, X., He, G., Guo, J., Lin, C., Yin, L., Zhao, J., Ma, Z., Ma, F., Li, Y., Hu, R., Wei, L., & Wang, C. (2020). Genomic Insights into the Demographic History of Southern Chinese. bioRxiv.

[3] Léonard Aurousseau : La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère), Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient. Tome 23, 1923. pp. 136-264

[4] Lang Linh: Người Việt có bị đồng hóa hay không ? Lược Sử Tộc Việt.

[5] Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin 1976 The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

[6] Đổng Sở Bình 董楚平; “Phương Việt hội thi” “方钺会矢” – Một trong những diễn giải về các nhân vật Lương Chử 良渚文字释读之一[J];东南文化;2001年03期.

[7] Edouard Chavannes: Mémoires historiques. Tome 1

[8] Nguyễn Hải Hoành: Tiếng ta còn thì nước ta còn. Bản sắc văn hóa Việt Nam.

[9] Bernard Philippe Groslier : Indochine. Carrefour .Editions Albin Michel. 1960.

[10] Paul Mus: Sociologie d’une guerre. Editions Seuil 1952.