Naissance de l’Indochine.

Apports de l’Inde et de la Chine.

Version française

Version anglaise

Thuật ngữ Đông Dương lần đầu tiên được nhà địa lý người Pháp-Đan Mạch Conrad Malte-Brun (1775-1826) sử dụng trong tác phẩm « Précis de la Géographie Universelle » xuất bản tại Paris năm 1810. Đây cũng là cách thức mà nhà địa lý Pháp dùng để nói đến ảnh hưởng của hai nền văn hóa quan trọng Ấn Độ và Trung Quốc đối với các dân tộc và quốc gia ở lục địa Đông Nam Á (Miến Điện, Cao Miên, Lào, một phần Mã Lai, Tân Gia Ba, Thái lan và Vietnam). Dựa trên dữ liệu khảo cổ học, chúng ta đã thấy rằng từ thế kỷ thứ 1 sau Công nguyên, người Ấn Độ đã bắt đầu dùng thuyền đi dọc theo bờ biển Đông Nam Á đến quần đảo Sunda.

Nguyên nhân của các cuộc phiêu lưu trên biển nầy có một phần không ít từ việc truyền giáo của Phật giáo bởi vì những người Ấn Độ nầy phần đông là cư dân thủy thủ ở vùng Amaravati, những người sùng bái Đức Phật Dipankara, người bảo vệ họ tránh khỏi những nguy hiểm của biển cả mà cũng có thể đến từ việc giao thương nhất là viên hoa tiêu người Hy Lạp Hippale đã phát hiện ra sự luân định kỳ của gió mùa vào khoảng giữa thế kỹ thứ 1 sau Công Nguyên khiến có sự tăng trưởng kỳ diệu các thương mại đường biển giữa Ấn Độ và các cảng biển thuộc Hồng Hải, cửa ngõ của phương Tây. Thời đó, hoàng đế Auguste của thành phố La Mã xa hoa muốn có vàng và những sản phẩm ở Ấn Độ như trầm hương, quế, hạt tiêu, đinh hương, bạch đậu khấu, sừng tê giác và ngà voi. Ấn Độ thời đó có liên hệ thương mai trực tiếp với Trung Ðông và gián tiếp với các nước vùng Ðịa Trung Hải như Ðế quốc La Mã.

Nhưng tiếc thay những sản phẩm nầy trở thành khan hiếm ở lục địa Ấn Độ buộc cư dân ở đây phải đi tìm những sản phẩm này từ xa và bằng mọi giá. Khi đến gần những bờ biển xa lạ của Đông Nam Á và sau đó họ phải tiến sâu trên đất liền qua thảm thực vật ngột ngạt để họ có thể đến được gặp những cư dân đầu tiên sống trên vùng cao nguyên. Họ cần phải thuyết phục những người nầy để được có những vật phẩm mà họ cần mua với sự thương lượng giá cả một cách công bằng. Tất cả những điều này họ phải mất nhiều năm.

Họ buộc lòng phải thành lập các trạm giao dịch thực sự nhất là các chuyến đi biển về phía Đông của họ cũng cần được điều chỉnh theo gió mùa. Có những lúc họ phải chờ có đủ những sản phẩm hàng hóa hiếm có trước khi quay về Ấn Độ nên có thể mất cả năm nhất là phải đợi lúc thời tiết thuận tiện. Còn các thực phẩm mà họ cần dùng không thể vận chuyển trong những khoang tàu buộc lòng họ phải nghĩ cách bố trí các cánh đồng lúa ngập nước trên đất màu mỡ ở các đồng bằng châu thổ nơi họ đổ bộ để mua các sản phẩm hiếm có và nơi họ có thể dễ dàng canh tác nhất là họ rất sành sỏi trong kỹ thuật thoát nước và tưới tiêu (như ở Phù Nam). Như vậy họ có thể quay về khi thu hoạch được thực hiện và các khoang tàu được chứa đầy.

Chính nhờ vậy mà tư tưởng Ấn Độ đã được đưa đến để bồi đắp toàn bờ biển phía nam của Đông Dương; từ đồng bằng ven biển An Nam đến đồng bằng Mã Lai và từ đồng Ménam đến đồng bằng sông Mê Kông. Cũng nhờ đó người dân miền Nam Đông Dương đã học được tất cả các yếu tố của một nền văn minh cao hơn: viết ngôn ngữ của họ bằng nhờ bảng chữ cái Ấn Độ, nó vẫn còn tồn tại cho đến ngày hôm nay ở các nước Miến Điện, Thái Lan, Cao Miên và Ai Lao và dùng một dụng cụ vô song để suy nghĩ, đó là tiếng Phạn giống như vai trò dùng tiếng La Tinh ở Châu Âu vào thời Trung Cổ. Các văn bản thiêng liêng, các sử thi của Ấn Độ được đánh giá cao đến mức được du nhập vào mỗi quốc gia.

Ta còn chưa kể đến hiệu quả của các kỹ thuật khai thác đất đai và sản xuất thủ công và thiên văn học có khả năng tính toán lịch chính xác hơn bất kỳ các lịch nào mà ta biết đến, theo nhà khảo cổ Pháp Bernard Philippe Groslier. Chính Ấn Độ đã truyền bá không những hệ thống chính trị tập trung xung quanh nhà vua và tín ngưỡng tôn giáo mà luôn cả nghệ thuật.

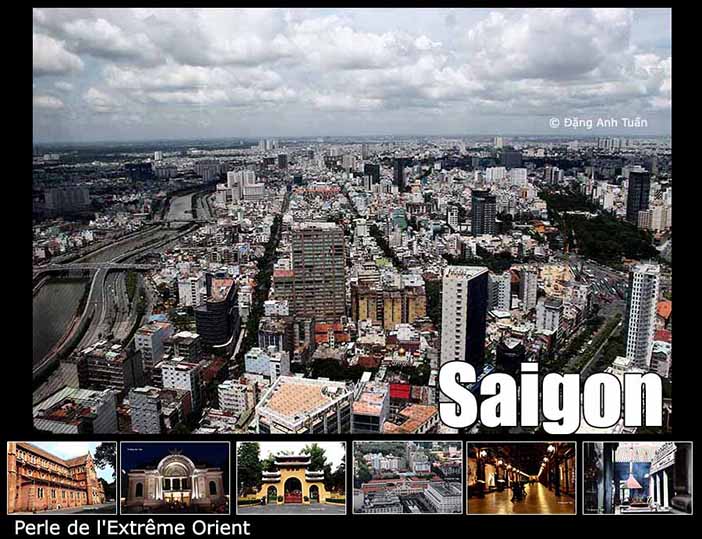

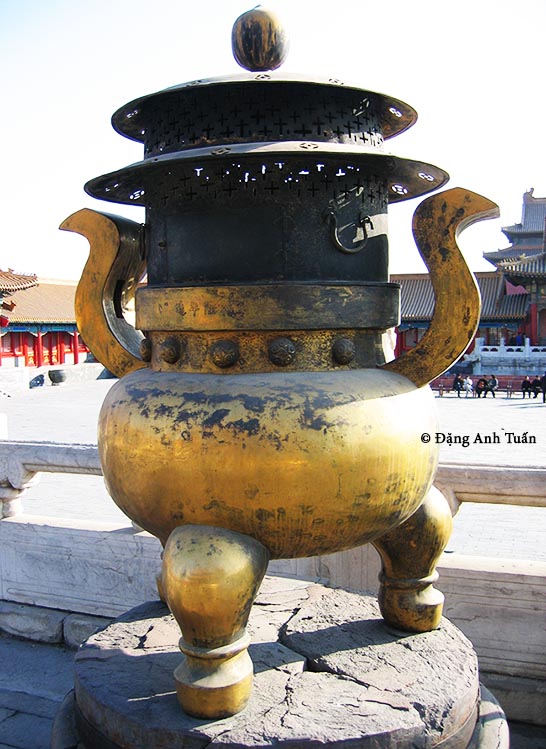

Các quốc gia này chưa bao giờ tự giam hảm mình trong một khuôn mẫu đóng kín và bất biến. Đông Nam Á sẽ được hình thành theo trường phái Bà La Môn thậm chí còn nhiều hơn theo mô hình Phật giáo. Trong những thế kỷ đầu của thời đại chúng ta, ở các quốc gia Ấn Độ Hóa, đồ đồng chỉ là những bản sao đơn giản và thuần túy của các tượng Phật Ấn Độ. Sau đó, giữa thế kỷ thứ 4 và thế kỷ thứ 5, các đồ đồng cho chúng ta thấy có sự tiến hóa và cách diễn giải riêng biệt, có thể xem đây là các tác phẩm địa phương nhưng vẫn còn chịu ảnh hưởng rõ ràng của Ấn Độ nhất là các trường phái phía bắc, điều này cũng rất bình thường nhất là có sự ưu việt của nền văn hóa Gupta ở thời kỳ này. Nổi tiếng nhất là bức tượng Phật bằng đồng tráng lệ được tìm thấy ở Đồng Dương, miền trung Việt Nam và được lưu giữ tại Bảo tàng Quốc gia Sàigon ngày nay. Chúng ta cũng có thể trích dẫn những tượng được tạc giống nhau như vậy ở Thái Lan tại Korat và Nakon Pathom (nền văn minh Môn Dvaravati).

Nhưng sau đó vào thế kỷ thứ 6 khi có những biến động chính trị và các cuộc xâm lăng man rợ cắt đứt con đường tơ lụa và gia vị khiến người Ấn Độ không còn mạo hiểm phiêu lưu trên biển. Họ cũng không còn nhớ đến sự tồn tại của các trạm giao dịch cũ của họ và trong các văn bản của họ, sử thi thương mại cũng được nhắc đến một cách qua loa. Sự xâm nhập và thẩm thấu của người Ấn Độ hình như lúc nào cũng mang tính chất hoà bình và nhờ đó các cư dân sống ở bờ biển phía nam mới thoái khỏi sự cô lập và được hình thành dựa trên văn hóa của người Ân Độ mà tạo ra được các nền văn minh mới và độc đáo như nền văn minh Óc Eo, Angkor Wat hay Chămpa. Người Ấ Độ không hề đi kèm theo phương thức chinh phục và thôn tính như người Trung Hoa với Việt Nam ở Đông Dương.

Qua truyền thuyết, nước ta khởi đầu có tên là Xích Qủy, một liên bang của người Bách Việt dưới quyền cai trị của Kinh Dương Vương Lộc Tục, cha của Lạc Long Quân ở phía nam sông Dương Tử (văn hóa Lương Chữ và Thạch Gia Hà) rồi sau đó có tên là Văn Lang của các vua Hùng đóng đô ở Phong Châu, có đất đai rộng lớn giáp ranh bắc đến hồ Động Đình, nam giáp nước Hồ Tôn (Chiêm Thành), đông giáp biển Nam Hải, tây nước Ba Thục (Tứ Xuyên). Nước Văn Lang bị thôn tính về sau bởi An Dương Vương, Thục Phán, người Tày ở Cao Bằng và trở thành sau đó vương quốc Âu Lạc đóng đô ở Cổ Loa huyện Đông An, Hà Nội khoảng chừng 3 thế kỷ trước Công Nguyên. Rồi Âu Lạc bị thôn tín về sau bởi Triệu Đà, một tướng lãnh của nhà Tần (Trung Hoa) và người sáng lập ra nước Nam Việt. Mặc dầu có các cuộc nổi dậy của hai Bà Trưng năm 39-43 SCN (sau Công Nguyên), Bà Triệu năm 225-248 SCN và Lý Bổn (Lý Nam Đế) năm 544 SCN, nước ta (Tonkin) vẫn tiếp tục dưới ách thống trị của Trung Hoa cho đến năm 938.

Người Hoa cố tình hủy diệt các trống đồng của người Việt để có thể đồng hóa được người dân Việt. Sự Hán hóa do đó lan truyền bằng cách hành động gương mẫu mà cũng bằng cách dùng vũ lực ense et aratro: bằng kiếm và lưỡi cày giống như cách người La Mã khuất phục châu Âu. Đất nước ta (Giao Chỉ) được tổ chức theo mẫu hình Trung Quốc: tỉnh, quận, phủ tạo thành khuôn khổ hành chính, nơi có quyền lực và thậm chí cả quyền lực cao nhất được giao phó cho người bản xứ nhưng được thực thi theo luật lệ Trung Quốc và tất cả đều tùy thuộc ở hoàng đế, người có thẩm quyền tối cao. Tiếng Hán trở thành ngôn ngữ chính thức và được sử dùng từ nay ở khắp đất nước.

Việt Nam tuy là một tỉnh lị của Trung Hoa vào thời đó (từ -111 đế n 938) nhưng Việt Nam vẫn còn là một trạm tiếp nối thật sự giữa Trung Hoa và Ấn Độ. Việt Nam được tiếp thu rất sớm Phật pháp từ đầu thế kỷ thứ nhất của kỷ nguyên Tây lịch vì Việt Nam nằm ở bên cạnh các nước như Phù Nam và Chiêm Thành thường thông dùng chữ Phạn của các kinh Phật và còn đươc các thương gia Ấn Độ ở lại để nghĩ, cung cấp và trao đổi hàng hóa. Chính vì vậy Phật giáo ở Giao Châu do từ Ấn Độ truyền sang trực tiếp chớ không phải đến từ Trung Hoa.

Nói tóm lại, việc Hán Hóa nhằm để mở rộng đế chế Trung Hoa chớ có bao giờ người Hoa nghĩ rằng việc Hán Hóa Việt Nam sẽ gieo mầm cho sự tiến hóa tiếp theo của toàn cả Đông Dương. Người Hoa muốn tạo con người Việt theo hình ảnh của họ nhưng họ đâu ngờ họ biến người dân Việt thành một dân tộc kiên trì, sẳn sàng chờ đợi thời điểm thích hơp để dành lại độc lâp nhất là họ đến từ văn hóa rực rỡ Lương Chữ và Thạch Gia Hà và thông thạo binh pháp của Tôn Tử cũng như người Hoa.

Được xem như những người báo hiệu của nền văn hóa Trung Hoa, người dân Việt chinh phục về sau bán đảo, đồng hóa và sau đó tiêu diệt các nước Ấn Độ hóa (Chân Lạp, Chiêm Thành) một cách triệt để giống như cách họ đã bị thôn tính bởi người Trung Hoa lúc ban đầu.

Bởi vậy ta thường nghe câu nói của các nhà khảo cổ về bán đảo Đông Dương như sau: Trung Quốc thống trị và đồng hóa, Ấn Độ gieo mầm của những bông hoa nhân văn phong phú. Đông Dương đã có thể hưởng lợi từ những bài học của những bậc thầy vô song Trung Quốc và Ấn Độ, mỗi nước để lại cho bán đảo một hệ thống chính trị và một dấu ấn riêng biệt và khó phai mờ theo dòng lịch sử.

Từ đó bán đảo mới có tên là Đông Dương do nhà địa lý người Pháp-Đan Mạch Conrad Malte-Brun đề xướng nhưng đọc giả đừng có nhầm lẫn với Đông Dương thuộc Pháp.(Indochine Française).

Version française

Le terme « Indochine » a été utilisé pour la première fois par le géographe franco-danois Conrad Malte-Brun (1775-1826) dans son œuvre intitulé « Précis de la Géographie Universelle », publié à Paris en 1810. C’est également ainsi que le géographe français désignait l’influence de deux cultures importantes, l’Inde et la Chine, sur les peuples et les nations de l’Asie du Sud-Est continentale (Birmanie, Cambodge, Laos, une partie de la Malaisie, Singapour, Thaïlande et Vietnam). Les données archéologiques montrent qu’à partir du Ier siècle de notre ère, les Indiens ont commencé à utiliser des bateaux pour longer les côtes de l’Asie du Sud-Est jusqu’aux îles de la Sonde.

La cause de ces aventures maritimes n’était pas seulement due à la prédication du bouddhisme, car ces Indiens étaient pour la plupart des marins de la région d’Amaravati, dévots du Bouddha Dipankara, qui les protégeait des dangers de la mer, mais aussi au commerce, en particulier au navigateur grec Hippale, qui découvrit la rotation périodique des moussons vers le milieu du premier siècle après J.-C., ce qui conduisit à la croissance miraculeuse du commerce maritime entre l’Inde et les ports de la mer Rouge, porte d’entrée de l’Occident.

À cette époque, l’empereur Auguste de la luxueuse cité romaine, souhaitait s’approvisionner en or et en produits d’Inde, tels que le bois d’aigle, la cannelle, le poivre, le clou de girofle, la cardamome, la corne de rhinocéros et l’ivoire. L’Inde entretenait alors des relations commerciales directes avec le Moyen-Orient et indirectes avec les pays méditerranéens, comme l’Empire romain.

Malheureusement, ces produits se raréfièrent dans le sous-continent indien, obligeant ainsi les habitants de ce pays à les rechercher de loin et à tout prix. Lorsqu’ils approchèrent des rivages étranges de l’Asie du Sud-Est, ils durent s’enfoncer dans les terres à travers une végétation étouffante pour atteindre les premiers habitants des hautes terres. Il leur fallut convaincre ces derniers de leur fournir les articles dont ils avaient besoin et négocier des prix équitables. Tout cela leur prit de nombreuses années.

Ils furent contraints d’établir de véritables comptoirs commerciaux, d’autant plus que leurs voyages maritimes vers l’Est devaient être modulés en fonction des moussons. Il leur fallait parfois attendre l’arrivée de denrées rares avant de rentrer en Inde, ce qui pouvait prendre une année entière, surtout si le temps était favorable. Quant à la nourriture dont ils avaient besoin, impossible à transporter dans les cales des navires, ils furent contraints de penser à mettre en place des rizières inondées sur les terres fertiles des deltas où ils débarquaient pour acheter des denrées rares et où ils pouvaient les cultiver plus facilement, car ils maîtrisaient parfaitement les techniques de drainage et d’irrigation (comme au Funan). De cette façon, ils pouvaient rentrer lorsque la récolte était terminée et que les cales étaient bien remplies.

C’était ainsi que les idées indiennes ont été introduites et ont fertilisé toute la côte sud de l’Indochine, des plaines côtières d’Annam à celles de la Malaisie, du delta du Ménam à celui du Mékong. C’est aussi par ce biais que les peuples du sud de l’Indochine ont appris tous les éléments d’une civilisation supérieure: ils ont écrit leur langue grâce à l’alphabet indien, qui existe encore aujourd’hui en Birmanie, en Thaïlande, au Cambodge et au Laos, et ils ont utilisé un instrument incomparable à penser, le sanscrit, similaire au rôle du latin en Europe moyenâgeuse. Les textes sacrés, les épopées de l’Inde, étaient si prisés qu’ils ont été introduits dans chaque pays.

On oublie de parler de l’efficacité des techniques d’aménagement du territoire, de l’artisanat et de l’astronomie, permettant de calculer les calendriers avec une précision inégalée, selon l’archéologue français Bernard Philippe Groslier. C’est aussi l’Inde qui a propagé non seulement un système politique centré autour du roi et des croyances religieuses, mais aussi les arts.

Ces nations ne se sont jamais cantonnées à un modèle fermé et immuable. L’Asie du Sud-Est sera davantage façonnée par l’école brahmanique que par le modèle bouddhiste. Aux premiers siècles de notre ère, dans les pays indianisés, les bronzes étaient de simples et pures copies des images du Bouddha indien.

Puis, entre le IVe et le Ve siècle, les bronzes témoignent d’une évolution et d’une interprétation distinctes. On peut les considérer comme des œuvres locales, mais toujours clairement influencées par l’Inde, notamment par les écoles du Nord, ce qui est d’ailleurs tout à fait normal compte tenu de la prédominance de la culture Gupta à cette époque. Le plus célèbre est le magnifique Bouddha en bronze découvert à Đồng Dương au centre du Vietnam, et conservé aujourd’hui au Musée national de Saïgon. On peut également citer des sculptures similaires en Thaïlande, à Korat et Nakon Pathom (civilisation Môn Dvaravati).

Mais au VIe siècle, lorsque les bouleversements politiques et les invasions barbares coupèrent les routes de la soie et des épices, les Indiens cessèrent de s’aventurer en mer. Ils oublièrent également l’existence de leurs anciens comptoirs commerciaux et, dans leurs écrits, l’épopée du commerce fut également évoquée d’une manière sommaire. La pénétration et l’influence des Indiens semblèrent toujours pacifiques, ce qui permit aux habitants de la côte sud de sortir de l’isolement et de créer ainsi des civilisations nouvelles et uniques comme Oc Eo, Angkor Vat ou Champa en se formant à partir de leur culture. Ils n’ont pas suivi la méthode de conquête et d’annexion comme les Chinois avec le Vietnam en Indochine.

Selon la légende, notre pays s’appelait à l’origine Xích Qủy (Pays des démons rouges), une fédération des Bai Yue sous le règne de Kinh Dương Vương (ou Lộc Tục) , père de Lạc Long Quân au sud du fleuve Yangtze (cultures de Lianzhou et Shijiahé). Puis il fut nommé d’abord Văn Lang des rois Hùng avec la capitale se trouvant à Phong Châu et ayant un grand territoire bordé au nord par le lac Dong Dinh, au sud par le pays Hồ Tôn (Champa), à l’est par la mer de Chine méridionale et à l’ouest par le royaume Ba Thục (Sichuan). Il fut annexé ensuite par An Dương Vuong, de nom Thục Phán issu des minorités Tày à Cao Bằng et devint plus tard le royaume Âu Lạc dont la capitale se trouvait à Cổ Loa, dans le district de Đồng An, Hanoï vers 3 siècles avant J.C.

Ce dernier fut ensuite annexé par Zhao To (Triệu Đà), un général de la dynastie des Qin (Chine) et fondateur du royaume Nan Yue. Malgré les soulèvements des deux sœurs Trưng (39-43 apr. J.-C.), Dame Triệu (225-248 apr. J.-C.) et de Lý Bổn (ou roi Lý Nam Đế) en 544 apr. J.-C., notre pays (le Tonkin) resta sous domination chinoise jusqu’en 938.

Les Chinois détruisirent délibérément tous les tambours de bronze vietnamiens afin d’assimiler le peuple vietnamien. La sinisation s’étendit ainsi par l’exemple autant que par la force, ense et aratro : par le glaive et le soc de charrue, exactement de la même façon que les Romains soumirent l’Europe. Notre pays (Jiaozhi) était organisé selon le modèle chinois : provinces, districts et préfectures formaient le cadre administratif, où le pouvoir, et même le plus haut, était confié aux autochtones, mais il s’exerçait selon la loi chinoise et dépendait entièrement de l’empereur représentant l’autorité suprême. Le chinois devint la langue officielle et fut désormais utilisé dans tout le pays.

Bien que le Vietnam fût le protectorat chinois (de -111 à -938), il était pourtant le véritable relais entre la Chine et l’Inde. L’implantation du bouddhisme fut très tôt dans ce pays au début de l’ère chrétienne car le Vietnam était non seulement à côté des pays se servant de sanskrit pour les textes bouddhiques comme le Founan (Phù Nam) et le Champa mais aussi le point de passage obligatoire pour les commerçants indiens. Ceux-ci avaient besoin de se reposer, approvisionner la nourriture et échanger les marchandises.

En somme, la sinisation visait à agrandir l’empire chinois, mais les Chinois n’ont jamais pensé que la sinisation du Vietnam allait semer les graines de l’évolution future de l’Indochine tout entière. Les Chinois voulaient créer le peuple vietnamien à leur image, mais ils ne s’attendaient pas à ce qu’ils transformaient, les Vietnamiens en un peuple opiniâtre, prêt à attendre le moment propice pour recouvrer son indépendance, d’autant plus qu’ils étaient issus de la brillante culture de Liangzhu et qu’ils connaissaient parfaitement l’art de guerre de Sun Tzu comme eux.

Étant considérés comme les fourriers de la culture chinoise, les Vietnamiens vont gagner la péninsule, assimiler puis détruire les pays indianisés (Chenla, Champa) aussi radicalement qu’ils avaient été eux-mêmes conquis par les Chinois en premier lieu.

C’est pourquoi les archéologues sont habitués à faire la remarque suivante à propos de la péninsule indochinoise: la Chine a dominé et assimilé, l’Inde a semé les germes des plus riches floraisons humanistes. L’Indochine a pu bénéficier des leçons des maîtres incomparables de la Chine et de l’Inde, qui ont laissé chacun, un système politique et une empreinte distincte et indélébile au fil des siècles.

Dès lors, la péninsule fut nommée Indochine par le géographe franco-danois Conrad Malte-Brun, mais les lecteurs ne doivent pas la confondre avec l’Indochine française.

English version

The term “Indochina” was first used by the Franco-Danish geographer Conrad Malte-Brun (1775-1826) in his work entitled “Précis de la Géographie Universelle” (Summary of Universal Geography), published in Paris in 1810. This is also how the French geographer referred to the influence of two important cultures, India and China, on the peoples and nations of mainland Southeast Asia (Burma, Cambodia, Laos, a part of Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam). Archaeological data show that from the 1st century AD, Indians began to use boats to sail along the coasts of Southeast Asia to the Sunda Islands.

The cause of these maritime ventures was not only due to the preaching of Buddhism, as these Indians were mostly sailors from the Amaravati region, devotees of the Buddha Dipankara, who protected them from the dangers of the sea, but also to trade, particularly to the Greek navigator Hippalus, who discovered the periodic rotation of the monsoons around the middle of the first century AD, which led to the miraculous growth of maritime trade between India and the ports of the Red Sea, the gateway to the West.

At that time, Emperor Augustus of the luxurious Roman city wished to procure gold and products from India, such as eaglewood, cinnamon, pepper, clove, cardamom, rhinoceros horn, and ivory. India then maintained direct trade relations with the Middle East and indirect ones with Mediterranean countries, such as the Roman Empire. Unfortunately, these products became scarce in the Indian subcontinent, forcing the inhabitants of this country to seek them from afar and at any cost. When they approached the strange shores of Southeast Asia, they had to venture inland through dense vegetation to reach the first inhabitants of the highlands. They had to convince the latter to supply them with the items they needed and negotiate fair prices. All this took them many years.

They were forced to establish genuine trading posts, especially since their maritime voyages to the East had to be adjusted according to the monsoons. Sometimes they had to wait for the arrival of rare goods before returning to India, which could take an entire year, particularly if the weather was favorable. As for the food they needed, which was impossible to transport in the ship’s holds, they were compelled to consider setting up flooded rice paddies on the fertile lands of the deltas where they landed to buy rare goods and where they could cultivate them more easily, as they had mastered drainage and irrigation techniques perfectly (as in Funan). In this way, they could return when the harvest was finished and the holds were well filled.

This is how Indian ideas were introduced and fertilized the entire southern coast of Indochina, from the coastal plains of Annam to those of Malaysia, from the Menam delta to that of the Mekong. It is also through this channel that the peoples of southern Indochina learned all the elements of a superior civilization: they wrote their language using the Indian alphabet, which still exists today in Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, and they used an incomparable instrument for thinking, Sanskrit, similar to the role of Latin used in medieval Europe. The sacred texts, the epics of India, were so prized that they were introduced into every country.

We forget to talk about the effectiveness of land management techniques, craftsmanship, and astronomy, which allowed calendars to be calculated with unparalleled precision, according to the French archaeologist Bernard Philippe Groslier. It is also India that spread not only a political system centered around the king and religious beliefs but also the arts.

These nations never confined themselves to a closed and immutable model. Southeast Asia would be shaped more by the Brahmanical school than by the Buddhist model. In the early centuries of our era, in the Indianized countries, the bronzes were simple and pure copies of Indian Buddha statues.

Then, between the 4th and 5th centuries, the bronzes show an evolution and a distinct interpretation. They can be considered local works, but still clearly influenced by India, particularly by the Northern schools, which is quite normal given the predominance of Gupta culture at that time. The most famous is the magnificent bronze Buddha discovered in Đồng Dương in central Vietnam, now preserved at the National Museum of Saigon. Similar sculptures can also be found in Thailand, in Korat and Nakon Pathom (Mon Dvaravati civilization).

But in the 6th century, when political upheavals and barbarian invasions cut off the silk and spice routes, the Indians stopped venturing out to sea. They also forgot the existence of their ancient trading posts, and in their writings, the epic of commerce was only mentioned in a summary manner. The penetration and influence of the Indians always seemed peaceful, which allowed the inhabitants of the southern coast to come out of isolation and thus create new and unique civilizations such as Oc Eo, Angkor Wat, or Champa, forming from Indian culture. The Indians did not follow the method of conquest and annexation like the Chinese did with Vietnam in Indochina.

According to legend, our country was originally called Xích Qủy (Land of the Red Demons), a federation of the Bai Yue under the reign of Kinh Dương Vương (or Lộc Tục), father of Lạc Long Quân, south of the Yangtze River (Lianzhou and Shijiahé cultures). Then it was first named Văn Lang under the Hùng kings, with the capital located at Phong Châu and a large territory bordered to the north by Dong Dinh Lake, to the south by the Hồ Tôn country (Champa), to the east by the South China Sea, and to the west by the Ba Thục kingdom (Sichuan). It was later annexed by An Dương Vương, named Thục Phán from the Tày people in Cao Bằng, and later became the Âu Lạc kingdom with its capital at Cổ Loa, in the Đồng An district, Hanoi, around the 3rd century BC.

The latter was then annexed by Zhao To (Triệu Đà), a general of the Qin dynasty (China) and founder of the Nanyue kingdom. Despite the uprisings of the Trưng sisters (39-43 AD), Dame Triệu (225-248 AD), and Lý Bổn (or Lý Nam Đế) in 544 AD, our country (Tonkin) remained under Chinese domination until 938.

The Chinese deliberately destroyed all Vietnamese bronze drums in order to assimilate the Vietnamese people. Sinicization thus spread both by example and by force, ense et aratro: by the sword and the plowshare, exactly in the same way the Romans subdued Europe. Our country (Jiaozhi) was organized according to the Chinese model: provinces, districts, and prefectures formed the administrative framework, where power, even the highest, was entrusted to the locals, but it was exercised according to Chinese law and depended entirely on the emperor representing the supreme authority. Chinese became the official language and was henceforth used throughout the country.

Although Vietnam was a Chinese protectorate (from 111 BC to 938 AD), it was nonetheless the true link between China and India. Buddhism was established very early in this country at the beginning of the Christian era because Vietnam was not only adjacent to the countries using Sanskrit for Buddhist texts such as Funan (Phù Nam) and Champa but also the mandatory passage point for Indian merchants. They needed to rest, supply food, and exchange goods.

In short, sinicization aimed to expand the Chinese empire, but the Chinese never thought that the sinicization of Vietnam would sow the seeds of the future evolution of the entire Indochina. The Chinese wanted to create the Vietnamese people in their own image, but they did not expect that they would transform the Vietnamese into a stubborn people, ready to wait for the right moment to regain their independence, especially since they came from the brilliant Liangzhu culture and were as well versed in Sun Tzu‘s art of war as they were.

Being considered as the suppliers of Chinese culture, the Vietnamese would enter the peninsula, assimilate, and then destroy the Indianized countries (Chenla, Champa) as radically as they themselves had first been conquered by the Chinese.

This is why archaeologists are accustomed to making the following observation about the Indochinese peninsula: China dominated and assimilated, India sowed the seeds of the richest humanistic flourishing. Indochina was able to benefit from the lessons of the incomparable masters of China and India, each of whom left behind a political system and a distinct and indelible imprint over the centuries.

From then on, the peninsula was named Indochina by the Franco-Danish geographer Conrad Malte-Brun, but readers should not confuse it with French Indochina.

Bibiographie:

Georges Cœdès : Cổ sử các quốc gia Ấn Độ Hóa ở Viễn Đông. Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới 2011

Bernard Groslier : Indochine. Carrefour des Arts. Editions Albin Michel 1960.