Portail du village Đường Lâm

Version vietnamienne

English version

Pictures Gallery

Ayant occupé à peu près 800 ha, le village Đường Lâm est localisé approximativement à 4km à l’ouest de la ville provinciale Sơn Tây. Il est consacré pratiquement à l’agriculture. Il est rare de trouver encore aujourd’hui l’un des villages ayant conservé les traits caractéristiques d’un village traditionnel vietnamien. Si la baie de Hạ Long est l’œuvre de la nature, Đường Lâm est par contre l’ouvrage crée par l’homme. Il est plus riche de signification que la baie de Hạ Long. C’est ce qu’a remarqué le chercheur thaïlandais Knid Thainatis. Effectivement Đường Lâm est riche non seulement en histoire mais aussi en tradition.

Dans les temps anciens, il s’appelait encore Kẻ Mia (pays de la canne à sucre). Selon une légende populaire, le métier de fabriquer de la mélasse de canne à sucre à Đường Lâm rapportait comment la princesse Mi Ê a trouvé une plante semblable à un roseau. Elle a pris une section de cette plante et a senti sa douceur fraîche et son goût aromatique. Elle a tellement aimé cette plante si bien qu’elle a conseillé aux gens de la cultiver. Au fil du temps, la canne à sucre poussait tellement dense qu’elle couvrait une grande surface comme le bois. La population locale a commencé à produire de la mélasse ainsi que des bonbons à partir de celle-ci. D’où le nom « Kẻ Miá ».

Grâce aux fouilles archéologiques aux alentours des contreforts de la montagne Ba Vi, on découvre que Đường Lâm était le territoire des Proto-Vietnamiens. Ces derniers y vivaient en grande concentration à l’époque de la civilisation de Sơn Vi. Ils continuaient à s’y établir encore durant les quatre cultures suivantes: Phùng Nguyên (2000-1500 BC), Đồng Dậu (1500-1000 BC), Gò Mun (1000-600 BC) et Đồng Sơn (700 BC-100 AD).

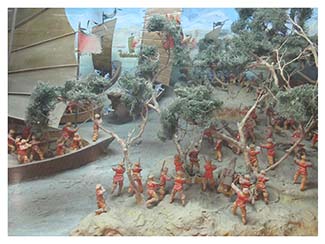

Le village est aussi la terre de deux rois célèbres Phùng Hưng et Ngô Quyền. Le premier, connu sous le nom « Bố Cái Đại Vương » (ou Grand roi père et mère du peuple) est adulé comme le libérateur de la domination chinoise à l’époque des Tang tandis que le deuxième a réussi à mettre fin à l’occupation chinoise de 1000 ans en défiant la flotte des Han du Sud (Nam Hán) sur le fleuve de Bạch Đằng. C’est aussi ici qu’on retrouve l’autel dédié à l’ambassadeur Giang Văn Minh auprès de la cour de Chine. Ce dernier fut tué par l’empereur des Ming Zhu Youjian (Sùng Trinh) car il a osé l’affronter en lui répondant du tac au tac avec le vers mémorable suivant:

Ðằng giang tự cổ huyết do hồng (Bạch Đằng từ xưa vẫn đỏ vì máu)

Le fleuve Bạch Ðằng continue à être teinté avec du sang rouge.

pour lui rappeler les victoires éclatantes et décisives des Vietnamiens contre les Chinois sur le fleuve Bạch Ðằng, suite au vers arrogant qu’il a reçu de la part de l’empereur chinois:

Đồng trụ chí kim đài dĩ lục (Cột đồng đến giờ vẫn xanh vì rêu).

Le pilier en bronze continue à être envahi par la mousse verte. (évoquant ainsi la période de pacification du territoire vietnamien par le général chinois Ma Yuan à l’époque des Han).

Làng cổ Đường Lâm

L’une des caractéristiques de ce village antique réside dans la préservation de son portail (porte principale) par lequel tout le monde doit passer. Le visiteur peut s’égarer facilement s’il n’arrive pas à repérer la maison communale Mông Phụ. Celle-ci est un bâtiment colossal édifié au centre du village avec son imposante charpente en bois de fer (gỗ lim). La plupart des maisons sont protégées par des blocs de murs en latérite et leurs porches sont parfois des petits chefs-d’œuvre qui ne peuvent pas laisser indifférent le visiteur. Le village Đường Lâm continue à garder son charme séculaire face à l’urbanisation galopante qu’on ne cesse pas de voir dans d’autres villages.

Có khoảng chừng 800 mẫu, làng cổ Đường Lâm nằm cách chừng 4 cây số về phiá tây của thị xã Sơn Tây. Làng nầy chuyên sống về canh nông. Rất hiếm còn tìm lại được ngày nay một trong những làng cổ còn giữ được những nét cá biệt của một làng Việtnam truyền thống. Nếu vịnh Hạ Long là một tác phẩm của tạo hóa thì làng cổ Đường Lâm ngược lại là một sản phẩm do con người tạo ra. Nó còn giàu có ý nghĩa nhiều hơn vịnh Hạ Long. Đây là sự nhận xét của nhà nghiên cứu Thái Knid Thainatis. Thật vậy Đường Lâm rất phong phú không những về lịch sữ mà còn luôn cả tập quán.

Thời xưa, Đường Lâm vẫn được gọi là Kẻ Mia (vùng đất trồng mía). Theo truyền thuyết, nghề làm mật mía ở Đường Lâm liên quan đến việc công chúa Mi E tìm thấy một loại cây giống cây sậy. Cô lấy một phần của cây này và ngửi thấy vị ngọt và hương vị thơm mát của nó. Cô rất yêu thích loài cây này nên đã khuyên mọi người nên trồng nó. Theo thời gian, cây mía mọc rậm rạp phủ kín cả một vùng rộng lớn như rừng. Người dân địa phương bắt đầu sản xuất mật mía cũng như kẹo từ nó. Do đó nó có tên là « Kẻ Miá« .

Nhờ các cuộc khai quật khảo cổ xung quanh ở chân núi Ba Vi, người ta phát hiện ra Đường Lâm là lãnh thổ của người Việt cổ. Những người sau này sống tập trung ở đây trong thời kỳ của nền văn hóa Sơn Vi. Họ vẫn tiếp tục định cư ở nơi nầy tiếp theo cho bốn nền văn hóa sau đây: Phùng Nguyên (2000-1500 TCN), Đồng Dậu (1500-1000 TCN), Gò Mun (1000-600 TCN) và Đồng Sơn (700 TCN-100 SCN).

Nơi nầy cũng là đất của hai vua cự phách Phùng Hưng và Ngô Quyền. Vua đầu tiên thường gọi là « Bố Cái Đại Vương » rất đuợc ngưỡng mộ vì ông là lãnh tụ khởi cuộc nổi dậy chống lại sự đô hộ của nhà Đường còn Ngô Quyền thì có công trạng kết thúc sự đô hộ quân Tàu có gần một thiên niên kỹ qua cuộc thách thức hải quân Nam Hán trên sông Bạch Đằng. Cũng chính nơi nầy mà cũng tìm thấy nhà thờ của thám hoa Giang Văn Minh. Ông đuợc đề cử sang Tàu xưng phong dưới thời Hậu Lê. Ông bị trảm quyết bỡi vua Tàu Minh Tư Tông Chu Do Kiểm (tức hoàng đế Sùng Trinh) vì ông không để vua Tàu làm nhục Việtnam dám đối đáp thẳng thắn với một vế đối lại như sau: Ðằng giang tự cổ huyết do hồng (Bạch Đằng từ xưa vẫn đỏ vì máu) nhắc lại những chiến công hiển hách trêng sông Bạch Đằng khi nhận một vế ngạo mạn của vua Tàu: Đồng trụ chí kim đài dĩ lục (Cột đồng đến giờ vẫn xanh) vì rêu ám chỉ đến cột đòng Mã Viện , thời kỳ quân Tàu đô hộ nước Việt dưới thời Đông Hán.

Một trong những đặc trưng của làng cổ nầy là sự gìn giữ cái cổng làng mà bất cứ ai đến làng cũng phải đi qua cả. Người du khách có thể bị lạc đường nếu không nhận ra hướng đi đến đình Mông Phụ. Đây là một toà nhà to tác được dựng ở giữa trung tâm của làng với một mái hiên oai vệ bằng gỗ lim. Tất cả nhà ở làng nầy phân đông được bảo vệ qua các bức tường bằng đá ong và các cổng vào thường là những kiệc tác khiến làm du khách không thể thờ ơ được. Làng cổ Đường Lâm tiếp diễn giữ nét duyên dáng muôn thưở dù biết rằng chính sách đô thị hoá vẫn phát triển không ngừng ở các làng mạc khác.

Occupying about 800 hectares, the village of Đường Lâm is located approximately 4 km west of the provincial town of Sơn Tây. It is practically dedicated to agriculture. It is rare to still find today one of the villages that has preserved the characteristic features of a traditional Vietnamese village. While Ha Long Bay is the work of nature, Đường Lâm, on the other hand, is a creation made by man. It is richer in meaning than Ha Long Bay. This is what the Thai researcher Knid Thainatis noticed. Indeed, Đường Lâm is rich not only in history but also in tradition.

In ancient times, it was still called Kẻ Mia (land of sugarcane). According to a popular legend, the craft of making sugarcane molasses in Đường Lâm tells how Princess Mi Ê found a plant resembling a reed. She took a section of this plant and felt its fresh sweetness and aromatic taste. She liked this plant so much that she advised people to cultivate it. Over time, the sugarcane grew so densely that it covered a large area like a forest. The local population began to produce molasses as well as candies from it. Hence the name « Kẻ Miá« .

Thanks to archaeological excavations around the foothills of Ba Vi mountain, it was discovered that Đường Lâm was the territory of the Proto-Vietnamese. They lived there in large concentrations during the Sơn Vi civilization period. They continued to settle there during the following four cultures: Phùng Nguyên (2000-1500 BC), Đồng Dậu (1500-1000 BC), Gò Mun (1000-600 BC), and Đồng Sơn (700 BC-100 AD).

The village is also the land of two famous kings, Phùng Hưng and Ngô Quyền. The first, known as « Bố Cái Đại Vương » (or Great King Father and Mother of the People), is revered as the liberator from Chinese domination during the Tang dynasty, while the second succeeded in ending 1,000 years of Chinese occupation by defeating the Southern Han fleet on the Bạch Đằng River. It is also here that the altar dedicated to ambassador Giang Văn Minh to the Chinese court is found. He was killed by the Ming emperor Zhu Youjian (Sùng Trinh) because he dared to confront him with a sharp retort in the memorable verse:

Ðằng giang tự cổ huyết do hồng (The Bạch Đằng River has always been red because of blood)

The Bạch Đằng River continues to be stained with red blood.

This was to remind him of the brilliant and decisive victories of the Vietnamese against the Chinese on the Bạch Đằng River, following the arrogant verse he received from the Chinese emperor:

Đồng trụ chí kim đài dĩ lục (Cột đồng đến giờ vẫn xanh vì rêu).

The bronze pillar is still green because of moss.

The bronze pillar continues to be overgrown by green moss. (thus evoking the period of pacification of the Vietnamese territory by the Chinese general Ma Yuan during the Han dynasty).

One of the characteristics of this ancient village lies in the preservation of its main gate through which everyone must pass. Visitors can easily get lost if they fail to locate the Mông Phụ communal house. This is a colossal building erected at the center of the village with its imposing ironwood frame (gỗ lim). Most houses are protected by laterite wall blocks, and their porches are sometimes little masterpieces that cannot leave visitors indifferent. The Đường Lâm village continues to retain its centuries-old charm in the face of the rampant urbanization that is constantly seen in other villages.

Bibliographie:

Lê Thanh Hương: An ancient village in Hanoi, Thế Giới publishers, Hànôi 2012