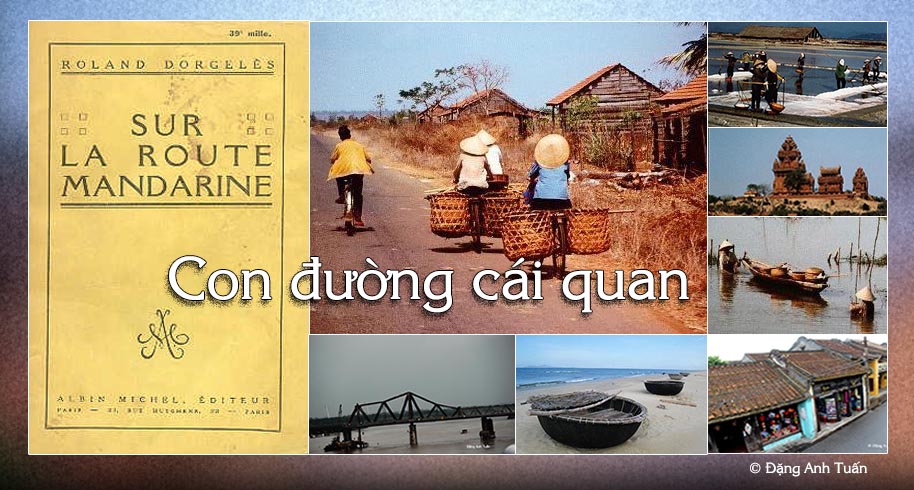

Con đường cái Quan

Nếu du khách có cơ hội đi từ Sài Gòn đến Hà Nội bằng ô tô thì bắt buộc phải đi « con đường cái quan » (hoặc Quốc Lộ số 1) vì đây là tuyến đường duy nhất ở Việt Nam. Tên này có tên là « con đường của các quan » mà người Pháp gọi nó như vậy bởi vì đây là tuyến đường trước đó được các quan lại và các quan chức cao cấp dùng để đi nhanh chóng dễ dàng giữa thủ đô và các tỉnh. Con đường này được sinh ra ở vùng đầm lầy của đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, đầy dãy các muỗi truyền nhiễm. Nó được bắt đầu ở Cà Mau và kết thúc tại đồn Đồng Đăng ở biên giới Trung-Việt gần vùng Lạng Sơn. Nó thường được xem là cột sống của đất nước trông nhìn như hồi hải mã (cá ngựa). Con đường này dài đến 1.730 cây số, nối liền một số thành phố, đặc biệt là Cà Mau, Bạc Liêu, Cần Thơ, Vĩnh Long, Sài Gòn (hay thành phố Hồ Chí Minh), Phan Thiết, Nha Trang, Quy Nhơn, Hội An, Đà Nẵng, Huế, Đồng Hới, Hà Tĩnh, Thanh Hóa, Ninh Bình, Hà Nội, Lạng Sơn.

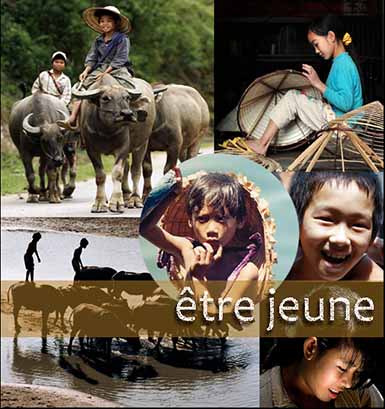

Con đường nầy thường được trán nhựa nhưng trải nhựa rất kém thường bị tắc nghẽn trên vài đoạn đường với một số xe vận tải, xe đạp, các người đi bộ, các đàn trâu, bò và các đàn vịt chạy lon ton. Nhựa đường hay thường bị nổ vỡ, làm cho bà cụ giật mình gác hai chân trên giá hành lý và những đứa trẻ ngồi trên những chiếc xe đạp quá lớn. Đây là những cảnh tượng bất thường hay gặp trên tuyến đường này.

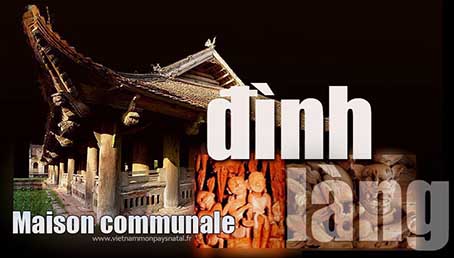

Ngoài ra còn có những mớ lúa hoặc sắn thu thập còn đang phơi khô trên các đường nhựa nung dưới ánh mặt trời ở miền Bắc. Trên con đường này, chúng ta có thể nhìn thấy ở phía Sa Huỳnh, các đầm lầy muối hoặc những ụ muối phủ đầy một lớp lá và được dựng theo dọc đường. Càng đi xa về phía bắc, chúng ta càng có được những quan cảnh yên bình của những cánh đồng lúa ngập nước. Chúng ta thường bắt gặp những đứa trẻ dẫn đầu đàn trâu dính bùn. Ở ngoại ô Hoa Lư, cố đô của Việt Nam, các hình bóng của những ngọn đồi núi đá vôi xuất hiện trong sương mù.Mặc dù tình trạng đường xá rất tồi tệ nhất là ở miền Bắc Việt Nam, nó vẫn tiếp tục là trục đường quan trọng của Việt Nam. Đối với những người thích tìm hiểu về lịch sử Việt Nam, lịch sữ của cuộc Nam tiến, chúng ta cần nên đi theo con đường này bởi vì chúng ta không chỉ thấy các di tích của một nền văn minh bị biến mất trong cơn lốc lịch sử, vương quốc Champa mà còn cả dấu ấn và dấu vết của những người định cư Việt Nam qua nhiều thập kỷ mà họ cố gắng áp đặt trong suốt thời gian họ đi qua. Biết con đường này là không chỉ biết đến những cánh đồng lúa mênh mông, những đồn điền cao su, những góc nhìn tuyệt đẹp dọc theo bờ biển Việt Nam, những toàn cảnh tuyệt vời từ đồng bằng này sang đồng bằng khác, các đèo vô cùng ngoạn mục đặc biệt là đèo Hải Vân, những ngọn đồi rừng rậm, những cánh đồng gần như hoang vắng nhưng cũng có một sức mạnh của đời sống nông nghiệp Việt Nam thông qua các ấp dọc theo con đường.

Biết con đường này là cũng biết đến cầu Hiền Lương. Cầu này do người Pháp xây dựng vào năm 1950, bị không quân Mỹ phá hủy năm 1967, dài được 178 mét, chắc chắn gợi lại một thời mà đất nước còn bị chia đôi với một nửa cầu được sơn màu đỏ và nửa còn lại màu vàng. Nó nằm ở trên vĩ tuyến 17, trong một khu vực có một đoạn đường được biết đến trong thời kỳ chiến tranh Đông Dương dưới cái tên « Đường không vui » vì quân đội Pháp gặp sự kháng cự quyết liệt ở nơi nầy. Biết tuyến đường này là biết đèo Hải Vân. Nó nằm 28 cây số về phía bắc của Đà Nẵng (hoặc Tourane) và chỉ có 496 thước so với mực nước biển. Cũng như tên gọi của nó, nó luôn ở trong mây vì nó rất gần biển, khiến nó lúc nào cũng nhận được một khối lượng lớn không khí ẩm thấp. Thưở xưa, nó đánh dấu biên giới giữa Bắc và Nam mà còn bảo vệ người Chămpa trước dục vọng xâm chiếm lãnh thổ của người dân Việt. Cố nhạc sỹ Phạm Duy có gợi đến con đường này qua tác phẩm được mang tên « Con Đường Cái Quan ».

Si le touriste a l’occasion de voyager de Saïgon à Hanoï en voiture, il est obligé de prendre la « route mandarine » (ou la route No 1) car c’est la seule qui existe sur le réseau routier du Vietnam. Ce nom « route mandarine », on le doit aux Français qui l’ont appelé car c’était la route prise autrefois par les mandarins et les hauts fonctionnaires pour voyager rapidement et aisément entre la capitale et leurs provinces. Cette route est née dans les marécages du delta du Mékong, infestés de moustiques. Elle commence à Cà Mau et se termine au poste de Ðồng Ðan de la frontière sino-vietnamienne dans la région proche de Lạng Sơn. On dit souvent qu’elle est la colonne vertébrale du pays au « look » d’hippocampe. Cette route est longue de 1730 km, reliant plusieurs villes, en particulier Cà Mau, Bạc Liêu, Cần Thơ, Vĩnh Long, Saïgon, Phan Thiết, Nha Trang, Qui Nhơn, Hội An, Ðà Nẵng, Huế, Ðồng Hới, Hà Tịnh, Thanh Hóa et Hanoï.

Elle est recouverte d’une manière générale d’asphalte, mais mal bitumée et encombrée souvent sur certains tronçons d’une multitude de camions, de vélos, de piétons, de buffles et de vaches et de troupeaux de canards qui trottinent. Le bitume explose souvent, faisant tressauter la mamie grimpée en amazone sur un porte-bagages et les mômes juchés sur des vélos trop grands. Ce sont des scènes insolites rencontrées fréquemment sur cette route.

On trouve aussi des récoltes de riz ou de manioc mises à sécher sur l’asphalte chauffée de soleil dans le Nord. Sur cette route, on peut voir du côté de Sa Huynh, des marais salants ou des monticules de sel recouverts de feuillage et dressés le long de la chaussée.

Plus on s’avance dans le Nord, plus on rencontre des paysages paisibles de rizières inondées. On croise souvent des enfants menant des troupeaux de buffles laqués de boue. Aux abords de Hoa Lư, l’ancienne capitale du Vietnam, les silhouettes des collines rocheuses émergent d’une brume bleutée.

Malgré son mauvais état surtout dans le Nord du Vietnam, elle continue à être l’axe routier vital du Vietnam. Pour ceux qui aiment connaître l’histoire du Vietnam, l’histoire de sa longue marche vers le Sud, il est conseillé d’emprunter cette route car on retrouve non seulement les vestiges d’une civilisation disparue dans le tourbillon de l’histoire, le royaume du Champa mais aussi les marques et les traces que les colons vietnamiens, depuis des décennies, arrivèrent à imposer lors de leur passage.

Galerie des photos

Connaître cette route c’est connaître non seulement des rizières immenses, des plantations d’hévéas, de beaux points de vue sur la côte du Vietnam, de très beaux panoramas d’un delta à un autre, de cols superbes (en particulier le col des Nuages ) et de collines boisées, des landes presque désolées mais aussi une intensité de vie agricole vietnamienne à travers les hameaux qui longent la route.

Connaître cette route c’est connaître aussi le pont Hiền Lương. Celui-ci construit par les Français en 1950, détruit par l’aviation américaine en 1967, long de 178m, évoque certainement une époque où le Vietnam était divisé et où la moitié du pont était peinte en rouge et l’autre moitié en jaune. Il est situé au 17ème parallèle, dans une zone où est situé un tronçon, connu lors de la guerre d’Indochine sous le nom « Rue sans Joie » car les troupes françaises y rencontrèrent de farouches résistances.

Quốc lộ số 1

Connaître cette route c’est connaître le col des Nuages. Celui-ci est situé à 28 km au Nord de Ðà Nang (ou Tourane) et seulement 496 m d’altitude. Comme son nom l’indique, il est toujours dans les nuages car il est proche de la mer, ce qui lui permet de recevoir d’importantes masses d’air humide. Autrefois, il marquait la frontière entre le Nord et le Sud et protégeait les Chams des appétits territoriaux vietnamiens.

Le compositeur Phạm Duy a évoqué cette route à travers son œuvre intitulé Con Ðường Cái Quan.

If the tourist has the opportunity to travel from Saigon to Hanoi by car, they must take the « Mandarin Road » (or Route No. 1) because it is the only one that exists on Vietnam’s road network. This name « Mandarin Road » comes from the French who called it that because it was the route formerly taken by mandarins and high officials to travel quickly and easily between the capital and their provinces. This road was born in the mosquito-infested swamps of the Mekong Delta. It starts in Cà Mau and ends at the Đồng Đan post on the Sino-Vietnamese border near the Lạng Sơn region. It is often said to be the backbone of the country with the « look » of a seahorse. This road is 1,730 km long, connecting several cities, particularly Cà Mau, Bạc Liêu, Cần Thơ, Vĩnh Long, Saigon, Phan Thiết, Nha Trang, Qui Nhơn, Hội An, Đà Nẵng, Huế, Đồng Hới, Hà Tịnh, Thanh Hóa, and Hanoi.

It is generally covered with asphalt, but poorly paved and often cluttered on certain sections with a multitude of trucks, bicycles, pedestrians, buffaloes, cows, and herds of ducks trotting along. The asphalt often cracks, causing the grandmother riding sidesaddle on a luggage rack and the kids perched on oversized bicycles to bounce. These are unusual scenes frequently encountered on this road.

You can also find rice or cassava harvests laid out to dry on the sun-heated asphalt in the North. On this road, near Sa Huynh, you can see salt marshes or mounds of salt covered with foliage and lined up along the roadside.

The further north you go, the more you encounter peaceful landscapes of flooded rice fields. You often come across children leading herds of buffaloes coated in mud. Near Hoa Lư, the ancient capital of Vietnam, the silhouettes of rocky hills emerge from a bluish mist.

Despite its poor condition, especially in northern Vietnam, it continues to be the vital road axis of Vietnam. For those who like to learn about the history of Vietnam, the story of its long march to the South, it is recommended to take this route because you not only find the remains of a civilization lost in the whirlwind of history, the Champa kingdom, but also the marks and traces that Vietnamese settlers, over decades, managed to impose during their passage.

Knowing this road means knowing not only vast rice fields, rubber plantations, beautiful viewpoints on the coast of Vietnam, stunning panoramas from one delta to another, magnificent mountain passes (especially the Cloud Pass), and wooded hills, almost desolate moorlands but also an intensity of Vietnamese agricultural life through the hamlets that line the road.

Knowing this road also means knowing the Hiền Lương bridge. This bridge, built by the French in 1950, destroyed by American aviation in 1967, and 178 meters long, certainly evokes a time when Vietnam was divided and half of the bridge was painted red and the other half yellow. It is located on the 17th parallel, in an area where a section, known during the Indochina War as the « Street Without Joy, » was situated because French troops encountered fierce resistance there.

Knowing this road is knowing the Cloud Pass. It is located 28 km north of Đà Nang (or Tourane) and only 496 meters above sea level. As its name suggests, it is always in the clouds because it is close to the sea, which allows it to receive significant masses of moist air. In the past, it marked the border between the North and the South and protected the Chams from Vietnamese territorial ambitions.

The composer Phạm Duy mentioned this road through his work titled Con Đường Cái Quan.