À quelle date la technique de la laque a-t-

Par contre, on sait que Hunan fit partie du royaume de Chu (Sỡ Quốc) établi sur la fleuve Yangzi (Dương Tử Giang) à l’époque des Royaumes Combattants. Ce dernier fut annexé plus tard par Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng). C’est aussi dans ce royaume de Chu qu’on a découvert les tombes de Mme Dai et de son fils à Mawangdui (Mã Vương Đôi) (Changsa, Hunan), (168 av. J.C.) où l’artisanat local montrait une maîtrise parfaite de la forme et de la couleur, en particulier les boiseries de la laque. Cela nous amène à avoir une idée précise et pouvoir conclure que la technique de la laque venait probablement des Bai Yue car le royaume de Chu était en contact étroit avec ces derniers et en recevait une influence notable en ce qui concerne la soie, la laque, les rites chamaniques des Hmong, les épées etc.

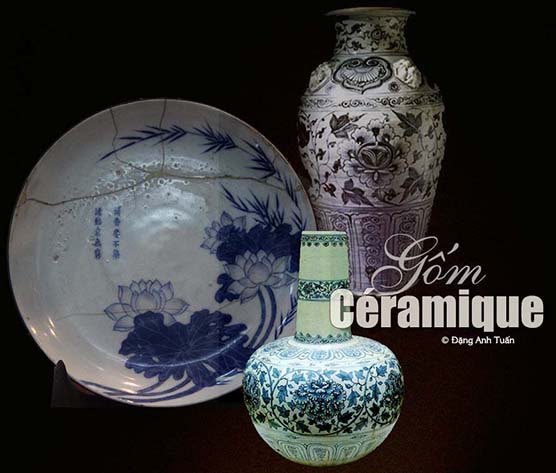

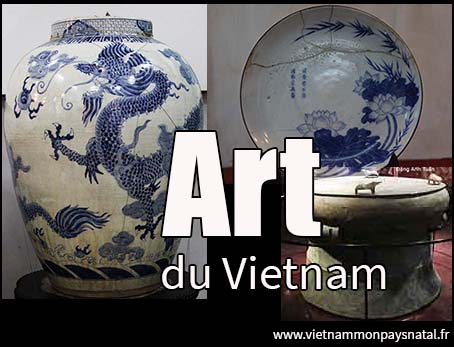

La laque est en fait le suc laiteux obtenu par incision du laquier. Grâce à la solidification à l’air libre et à la résistance à l’acide et aux éraflures, la gomme résineuse constitue une protection idéale pour les bois et pour les bambous. On se sert de cette résine dans la fabrication des objets laqués. Ceux-ci offrent une grande diversité: paravents, coffres, plateaux, vases, échiquiers etc. Le travail de laque nécessite beaucoup de préparations et de soins.

Sơn mài

Kỹ thuật sơn mài đã được du nhập vào Việt Nam từ lúc nào? Câu hỏi nầy vẫn tiếp tục duy trì các cuộc tranh luận và vẫn còn ngày nay là một đề tài bàn cãi. Đối với các nhà khảo cổ học, việc trang sức sơn mài đã bất nguồn từ cuộc xâm nhập đầu tiên của người Trung Hoa nhờ sự khám phá các di vật sơn mài tìm thấy trong các cổ mộ cố có từ thế kỷ 3 và 4 trước Công Nguyên. Còn các nhà nghiên cứu khác thì kỹ thuật sơn mài được du nhập ở thế kỷ 15 bỡi Trần Tường Công. Ông nầy được vua Lê Nhân Tôn (1443- 1460) phái đi sang Trung Quốc làm sứ thần và có trọng trách để tìm một nghề có thể đem lại nguồn lực mới cho người nông dân Việtnam. Ông được kết nạp bước đầu ở các xưởng Trung Hoa ở tỉnh Hồ Nam để thông hiểu kỹ thuật sơn mài. Nhưng ít có người tin về việc nầy cho đến ngày nay nhất là ở thời điểm đó những chuyện bia đặt nầy không thiếu nhằm với chủ đích hợp pháp hóa chính sách xâm lược đất đai và đồng hóa tất cả dân tộc bị cai trị. Ngược lại, chúng ta biết rằng Hồ Nam thuộc về Sở Quốc đựợc thiết lập trên sông Dương Tử thời Chiến Quốc. Sau nầy nước Sở bị Tần Thủy Hoàng thôn tính. Chính ở Sở quốc mà người ta khám phá được các ngôi mộ cổ của bà phu nhân tên Đại và con bà ở Mã Vương Đôi (Trường Sa, tỉnh Hồ Nam), vào thời nhà Hán (năm 168 trước Công Nguyên) mà thủ công nghệ đia phương biểu hiện sự khéo léo về màu sắc cũng như về hình dạng nhất là ở các gỗ sơn mài. Nhờ đó chúng ta có một cái nhìn chính xác và có thể kết luận là kỹ thuât sơn mài đến từ đại tộc Bách Việt vì Sở quốc thường có liên hệ thân thiết và nhận đuợc ở đại tộc nầy một ảnh hưởng trọng đại nhất là ở các lĩnh vực như tơ lụa, gươm giáo, nghi lễ đạo saman của dân tộc Hmong vân vân …..Sơn mài thật sự là nhựa sữa được lấy từ cây sơn ta qua các đường rach vào thân cây. Nhờ sự đông đặc ngoài trời và kháng cự hữu hiệu chống axit và các vết trầy nên gôm nhựa rất được thông dụng trong việc bảo vệ thích hợp cho các đồ vật làm bằng cây và tre. Vì vậy chất nhựa nầy được dùng trong việc chế tạo các đồ nội thất như các bình phong, rương, mâm, bình, bàn cờ tướng vân vân… Kỹ thuật sơn mài cần phải có nhiều giai đoạn chuẩn bi và chăm sóc tĩ mĩ.

At what date was the lacquering technique introduced in Vietnam? Its date of introduction continues to sustain debates and always remains the object of discussions. For some archaeologists, the use of lacquer adornment dated back to the first Chinese invasion (discovery of lacquerwares in the tombs of 3rd – 4th centuries of our era). For others researchers, this technique was introduced by Trần Tường Công, an ambassador at the court of China. He was assigned by king Lê Nhân Tôn (1443-1460 ) to find a trade contributing to provide new resources for peasants. He was introduced to the secrets of lacquer in Chinese workshops of Hunan province. Nobody is not really convinced until today because the Chinese pretence did not lack at this time for legitimating the policy of assimilation and territorial conquest vis à vis other people. On the other hand, one knowns Hunan was an integral part of the Chu kingdom (Sở Quốc) established on the Yangzi river (Dương Tử Giang) during the Warring States period. The latter was annexed thereafter by Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng). It is also in the Chu kingdom one has discovered the tombs of Mrs Dai and her son at Mawangdui (Mã Vương Đôi) (Trường Sa, Hồ Nam), (168 before J.C.) where the local craft showed the master’s degree in shape and color, in particular the lacquer panelling. We are brought to have a precise idea and conclude that the lacquering techniques probably came from the Bai Yue because the Chu kingdom was in close contact with the latter and got from which an important influence concerning silk, lacquer, shamanic rites of Hmong people, swords etc.

Lacquer is in fact the milky juice obtained from the incision of the lacquer tree. Thanks to the solidification in open air and the resistance to acid and scratches, the resinous gum constitutes an ideal protection for wood and bamboo. One uses this resin to make lacquerwares. They offer a great diversity: folding screens, chests, trays, vases, chessboard etc. Lacquerwork requires a lot of preparations and care