The exact date of the introduction of Buddhism to Vietnam is not known. According to the Vietnamese scholar Phan Lạc Tuyên, Indian monks came to Vietnam at the beginning of the Christian era based on the story of Chu Đồng Tử, who was initiated into Buddhism during his encounter with an Indian monk. This was also the period of the Three Kingdoms (Tam Quốc) when Vietnam was a Chinese province called Jiaozhi (Giao Châu) under the governance of Shi Xie (Sĩ Nhiếp). At that time, Vietnam belonged to the kingdom of Wu (Đông Ngô) led by Sun Quan (Tôn Quyền), whose mother, a fervent disciple, brought monks from Luy Lâu to Jianye (the capital of the kingdom of Wu), which corresponds to the current city of Nanjing (Nam Kinh), to ask them to preach and comment on Buddhist sutras.

The Buddhist center Luy Lâu became so prestigious and important that it soon attracted many famous Indian or foreign monks such as Ksudra (Khâu Đà Là), Mahajivaca (Ma Ha Kỳ Vực), Kang-Sen-Houci (Khương Tăng Hội), Dan Tian (Đàm Thiên). Being the senior monk of the Sui dynasty, the latter, upon his return to China, had the opportunity to report to Emperor Sui Wendi (Tùy Văn Đế) on the development of Vietnamese Buddhism: the province of Giao Châu had adopted Buddhism before us because, in addition to the construction of 20 pagodas, it had more than 500 monks and 15 collections of translated sutras.

This undeniably proves that Buddhism was flourishing at that time in Vietnam. It is important to recall that in the Chinese annals, there is mention of the pillaging by the Chinese army under General Lieou Fang (Lưu Phương) of the Sui dynasty (nhà Tùy). This general devastated the capital of Champa, Điển Xung (Kandapurpura), under the reign of King Sambhuvarman (Phạm Phạn Chí in Vietnamese) and took with him 1,350 Buddhist texts compiled in 564 volumes. Champa very early on promoted the establishment of Buddhism, as it was already mentioned by the famous monk Yijing (Nghĩa Tịnh) upon his return from his maritime journey in the Insulinde as one of the Southeast Asian countries that held the Buddha’s doctrine in high esteem at the end of the 7th century under the reign of Wu Ze Tian (Vũ Tắc Thiên) of the Tang dynasty (Nhà Đường).

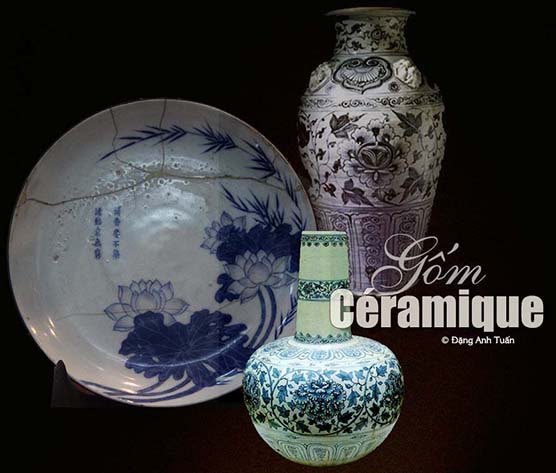

Although Vietnam was a Chinese protectorate (from 111 BC to 931 AD), it was nevertheless the true relay between China and India. The establishment of Buddhism was very early in this country at the beginning of the Christian era because Vietnam was not only next to countries using Sanskrit for Buddhist texts such as Founan (Phù Nam) and Champa but also the mandatory passage point for Indian merchants. They needed to rest, replenish food supplies, and exchange goods (silk, spices, eaglewood, cinnamon, pepper, ivory, etc.).

At that time, India had established trade relations directly with the Middle East and indirectly with Mediterranean countries such as the Roman Empire. Mahayana Buddhism flourished in India with the centers of Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda in the coastal region of southeastern India (Andhra Pradesh). This encouraged Indian monks to accompany sailors along the coasts of Malaysia, Funan, and Vietnam with the intention of spreading the faith. That is why it can be said that Vietnamese Buddhism came directly from India with Indian monks, but in no way was it brought by the Chinese.

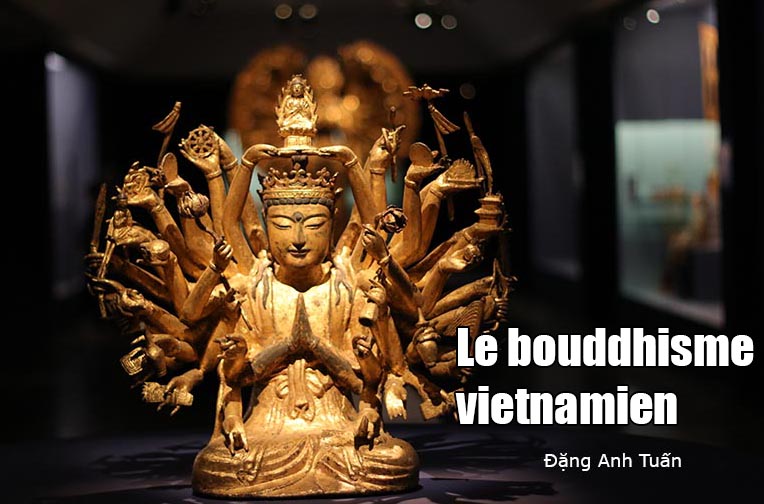

Vietnamese Buddhism, whose current is Mahayana, takes more into account collective salvation than individual salvation, whereas Theravada Buddhism considers salvation as the result of efforts made by the individual to achieve enlightenment and become a bodhisattva. At the beginning of its establishment, Buddhism encountered no resistance from the Vietnamese because it easily accepted their traditional paganism. It only had some simple and modest religious activities such as the veneration of the Buddha, offerings, acts of mercy, etc. Buddha was none other than Quán Thế Âm (Avalokitesvara) and Nhiên Đăng (Dipankara) because these figures protected sailors during sea voyages. The first Vietnamese Buddhist legends, Thích Quang Phật and Man Nương Phật Mẫu, also appeared at this time with the arrival of the monk Ksudra, also known as Kalacarya (the Black Master), in Vietnam.

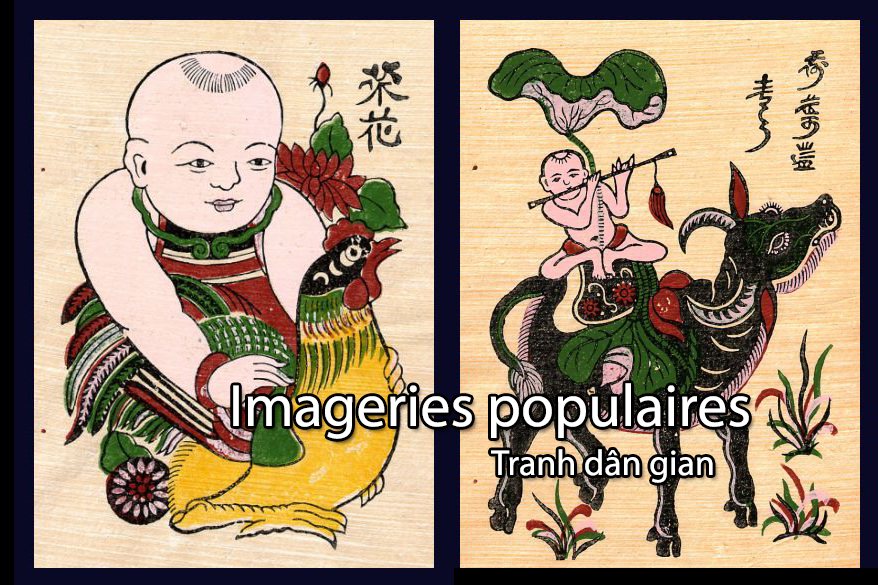

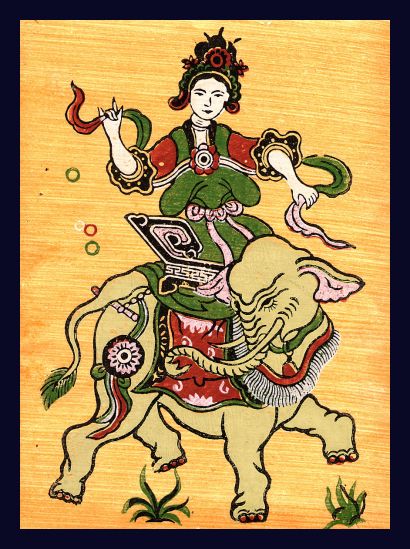

It is through these legends that Man Nương, upon her death, became an object of worship under the name « Mother Buddha or Phật Mẫu » by the Vietnamese. These legends thus testify to the ease of integrating popular beliefs into Buddhism. Furthermore, this religion, imported early on, was under Indian influence which, according to researcher Hà Văn Tấn, lasted until the 5th century.

The Chinese governor Sĩ Nhiếp (177-266) was often accompanied in the city by religious figures coming from India (người Hồ) or Central Asia (Trung Á) on each outing. The number of foreign monks was so significant that Giao Châu became a few years later the center for translating sutras, among which was the famous Saddharmasamadhi sutra (Pháp Hoa Tam Muội) translated by the monk Chi Cương Lương Tiếp (Kalasivi) in the course of the 3rd century.

It is also important to note that in a short period of six years (542-547), King Lý Nam Đế (Lý Bí) of the early Lý dynasty succeeded in freeing Vietnam from Chinese domination and ordered the construction of the Khai Quốc pagoda (Foundation of the Nation), which today is the famous Trấn Quốc pagoda in Hanoi. According to the Zen monk Thích Nhất Hạnh, it was mistakenly believed in the past that the Indian monk Vinitaruci introduced Vietnamese dhyana Buddhism (Thiền) at the end of the 6th century. During his stay in Lũy Lâu in the year 580, he resided in the Pháp Vân monastery belonging to the dhyana school. It was also at this time that the dhyana monk Quán Duyên was teaching dhyana there. Other Vietnamese monks had gone to China to teach dhyana before the arrival of the famous monk Bodhidharma, recognized as the patriarch of the Chinese dhyana school and the patriarch of Kungfu.From now on, it is known that it was the monk Kang-Sen-Houci of Sogdian origin (Khương Tăng Hội), instead of Vinitaruci (Ti Ni Lưu Đà Chi), who deserves the credit for introducing dhyana Buddhism to Vietnam.

Vietnamese Buddhism began to flourish and reach its golden age when Vietnam succeeded in regaining independence under General Ngô Quyền. Under the Đinh, Early Lê, Lý, and Trần dynasties, Buddhism was recognized as the state religion.