Đi tìm nguồn gốc dân tộc Việt (Phần 2)

In search of the Origin of the Vietnamese people

This remark has been confirmed by what was discovered in the tombs at the Guigi site of Jiangxi: The weapons found bore a symbolic characteristic because they were all made of wood. They did not have an important place in people’s life or after-live. This led to the conclusion that contrary to the society of the folks from the North, that of the Yue was rather more peaceful. That is why they were not able to resist better every time there was an encroachment by the neighbors from the North, the Yi did not stop at nibbling away their territory and pushing them a little farther south at each confrontation. The Yi themselves by their art of making bows and arrows. They were formidable warriors talented in arching and horse riding. Hardened by the roughness of nature, they were used to wrestling with wild animals and other tribes. That gave them at the start a gene of a conqueror and a fighter in their blood.

It was not the case of the folks from the South, the Bai Yue. The wise Confucius had the occasion to compare the forces that the folks from the North and from the South possessed respectively: Courage and power ( Dũng ) for the former and kindness and generosity ( Nhân từ ) for the latter. Again, the word Yi 夷 for origin the picture of a man 人 holding a bow 弓 gives us a pretty good idea on the particularity of the folks from the North. Under the direction of , Houang Di ( Hoàng Ðế ) they have succeeded in pushing back the first tribes of Bai Yue in the territory delimited by the yellow river Huang He and the YangTse river led by Chiyou ( Xi Vưu ) ( or Ðế Lai in Vietnamese ) in alliance with king Lôc Tục ( ou Kinh Dương Vương ) who reigned south of the blue River on a vast country of Xích Qủi ( Country of red demons ). According to a Chinese legend, this confrontation took place at Trác Lộc ( Zhuolu ) in the presently province of Hebei and has permitted the folks from the North to start progressively their expansion to the Blue River. The death of Chiyou marked the first victory of the folks from the North over the Bai Yue people some 3000 years B.C.

At the Shang period, none of the Chinese or Vietnamese historic documents talked about the relationship between the Bai Yue and the Shang besides the Vietnamese legend about « Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương » ( or the heavenly hero of Phù Ðổng village ) which reported a confrontation between the Shang and the Văn Lang kingdom of the Luo Yue. However it was noted that contact was established later between the Zhou dynasty and the king of the Luo Yue ( Hùng Vương ). A silver pheasant ( bach trĩ ) was offered by the latter to the king of Zhou according to the book Linh Nam Chích Quái. At the time of Spring and Autumn, a state of East Yue was known in the Mémoires Historiques by the historiographer of Han empire Si Ma Qian ( Tư Mã Thiên ) . It was the kingdom of the famous lord Gou Jian (Câu Tiễn). At the death of this one, his descendants did not succeed in maintaining hegemony. At the middle course of the Blue River, another kingdom, founded also by one of the Bai Yue tribes ( Bộc Lão ) and known as Chu ( Sở Quốc), took over at the time of Fighting Kingdoms and became one of the seven rival principalities ( Han, Zhao, Wei, Yan, Qi, Qin and Chu ).(Hàn, Triệu, Ngụy, Yên, Tề, Tần và Sỡ).

Terracotta warrior of Qin Shi Huang Di

Before being defeated by the army of Qin, the Chu kingdom has indirectly brought its undeniable contribution in favor of the future formation and unity of the Chinese nation by eliminating in 332 the state of East Yue of Goujian and starting to give a new impulsion to the development of a large state with the reforms of Wu Qi (Ngô Khởi).

The Tong Yue (or the Yue of Gou Jian) began to take refuge in the southern territory of Bai Yue after the annexation of their land by the Chu kingdom. According to Léonnard Aurousseau, after their defeat, the Yue of Gou Jian (or Tong Yue ) found asylum in large number in the following regions: Foujian (Phúc Kiến ), Guangdon ( Quảng Ðông ), Guangxi ( Quảng Tây ) and Jiaozhi ( Giao Chỉ ) and thus became the Man Yue ( Foujian ), Nan Yue (Jiangsu, Jiangxi) and Luo Yue (Quangxi, Jiaozhi). All were « sinisized » as centuries went by except the Luo Yue who were the legitime descendants of the Yue belonging to the Ngeou branch and were known often as Tây Âu (Xi Ngeou).

« There was no doubts on the origin of the Luo Yue », wrote the French scholar Leonard Aurousseau in his work « Notes sur les origines du peuple annamite ( Ghi chép nguồn gốc dân tộc An Nam ) » ( BEFEO, T XXIII, 1923, p.254 ). The other Yue peoples, particularly those living in the Chu kingdom were fast to follow them at the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang Di. This one did not hesitate to banish whoever dare resist his policy of assimilation, particularly the Yue and the Miao to forced labor on the construction of the Great Wall, to burn not only all the works of learned confucianists but also those of other unsubdued people and to maintain his policy of aggression against the Bai Yue as far as Ling Nan ( Linh Nam ). The conquest of the Xi Ou and Luo Yue (Tay Au) territory of Thục An Dương Vương that marked the second confrontation between the Chinese and the Bai Yue, was achieved in 207 with the nomination of two famous governors to the conquered territory: Nhâm Hiếu (Jen Hiao) and his assistant Triệu Ðà (Zhao Tuo).

In spite of the policy of terror and pacification, the Yue continued to run their resistance heroically. They hid in the bush and lived with the animals. No one agreed to become slave of the Chinese. The Yue picked their chiefs among their men of value. Then they attacked the Chinese at night and inflicted them with a great defeat…, that was reported in the translation of Huainan zi (Hoài nam tử) of L. Aurousseau, B.E.F.E.O. XXIII, 1923, p. 176.

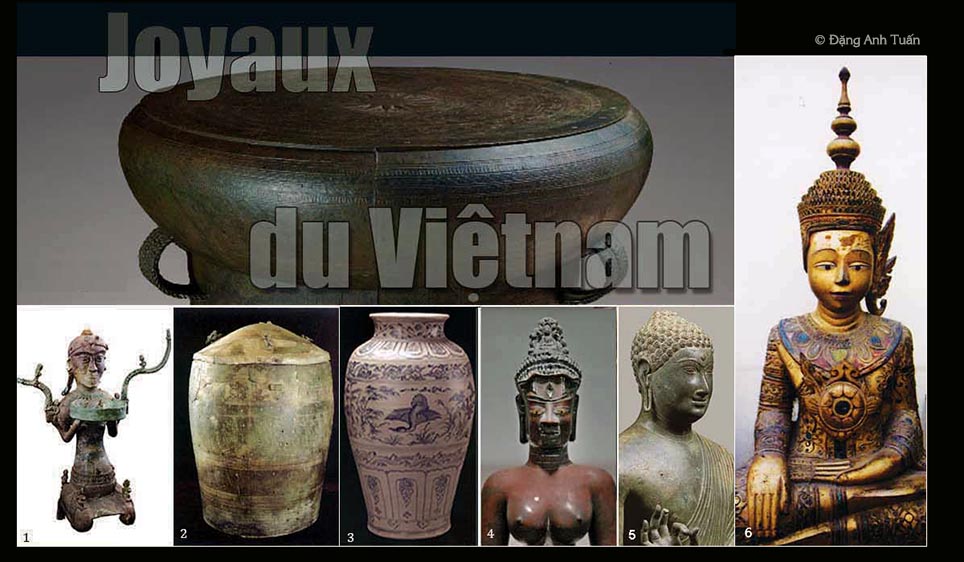

At the death of Nhâm Hiếu, taking advantage of consecutive troubles following the fall of the Qin empire in 207, Triệu Ðà. ( Zhao Tuo ) became allied with other Yue to declare independence fo the Nan Yue kingdom for which he took control of Guilin and Xiang then in 184 B.C., he attacked the Chang Sha region ( Hunan ( Hồ Nam )) . This kingdom was short-lived and fell back in the hands of the folks from the North, the Han in 111 B.C. despite the heroic resistance of Prime Minister Lục Gia. This confrontation, the third one with the people of Bai Yue took away not only their land but also their cultural identity. The sinization began its full steam on the conquered territory ( Foujian (Phuc Kien), Guizhou ( Qui Chau ), Guangdong ( Quảng Ðông ), Guangxi ( Quảng Tây ), Yunnan ( Vân Nam ), Tonkin ( Giao Chỉ ). Many revolts and insurrections broke out during this long period of Chinese domination. But the most dazzling revolt remained the one run heroically by the sisters Trưng Trắc, Trưng Nhị. On appeal of the sisters in 39 A.D., the Yue living in the South of China and a large part of Tonkin joined them. That helped them to stand up with the Han army until 43 A.D. But they were finally defeated by Ma Yuan ( Mã Viện ) a great Chinese marshal at the time. Ma Yuan ( Mã Viện ) assigned by the Han emperor, Guang Wu (Quang Võ) decided to destroy all bronze drums found on the land of the Luo Yue because he knew at the confrontation that those objects had the value as an emblem of power for them. According to what people said, to move back the frontier down to the Nam Quan border gate, he did not hesitate to erect a pillar several meters high made of bronze collected from the drums and bearing this sign:

Ðồng trụ triệt , Giao Chỉ diệt

Ðồng trụ ngã, Giao Chỉ bị diệt.

Bronze pillar falls, Giao Chi disappears

But that did not upset the will and ardor for independence of the Luo Yue ( the Viet ). They decided to consolidate the pillar by throwing a piece of earth around it when they went by, which progressively helped in building up a mound and made disappear the mythical pillar. To deal with any eventuality of revolt, there was also an order from empress Kao (Lữ Hậu) in 179 B.C. providing a ban on delivery of not only plowing and metal instruments but also horses, oxen and sheep to the Barbarians and the Yue. This has been reported by E. Gaspardone in his work titled » Matériaux pour servir à l’histoire de l’Annam » ( BEFEO, 1929 ). Because of this policy, it is not surprising to discover recently a large number of bronze drums burried in Vietnam and in neighboring areas ( Yunnan, Hunan ). The Ðồng Sơn civilization came to an end during the Chinese occupation.

Forced enlistment of the Yue into the army of the conquerors and the contacts they had with the Chinese as the years went by allowed them to know more about warfare technique (Sunzi (Tôn Tử) for example) and to improve their weapons in the struggle against the invaders in the years to come. On the other hand, the Chinese appropriated what belonged to the Yue during their long occupation. The Yue continued to be treated as barbarians despite their undeniable contribution to the radiance of Chinese culture. Those folks from the North could pretend from then on to be the legitimate holders of the Writing of Luo, the theory of Ying and Yang and the 5 elements, even though there exists a large number of incoherence in their mythical made up stories.

Reconstructed model found at the Banpo site

They modified the dragon, the preferred mythical animal of the Bai Yue, which had a start with an alligator’s head and a snake’s body, to fit their temperament of a warrior and their taste by giving it the wings and a horse’s trunk and definitely adopted it as their own symbolic animal even though they had the white tiger in their Turco – Mongol traditions. Their round form house whose model has been reconstructed and found at the Banpo site has been replaced by a spacious house with a roof largely « hollow-back » and overflowing in canopy, that of the Bai Yue. In the turmoil of history, there was no more room for the Bai Yue.

Except the Luo Yue, other peoples of Bai Yue continued to be « sinized » in a way that at the end of 10th century, on their land there were only two peoples face to face, a conquering people (the Han) and the rebellious people ( the Viet ) looking for independence. The states of Gou Yue, Nan Yue, Man Yue etc…thereafter took part in Southern China. Taking advantage of the breaking up of the Tang empire, the Luo Yue declared independence with Ngô Quyền. The Vietnamese nation began to see the day. One should not believe that everything went really smoothly and harmoniously. It cost such sacrifices in order for the folks from the North to accept the reality. That is how the history page of the Bai Yue was mixed up with that of the Luo Yue.

Have recent scientific discoveries radically changed the view about the Bai Yue and particularly their history? They have called into question he idea of cultural diffusionism originated from the North. More ancient vestiges than those at Hemudu have been discovered recently in the middle Blue river at Pentoushan ( Hunan ) . Could one continue to consider the Miao 苖, the Bai Yue as « barbarian » folks? Nevertheless the word Miao (or Miêu in Vietnamese) which is made of a ricefield picture ( Ðiền 田) added on its top the pictogram « Thảo » (cỏ) 艹( herb ) provides evidence how the Chinese depict in their language people knowing how to grow rice. Could we continue to maintain a traditional and obsolete version written by the conquerors to the detriment of the search for historic truth? It turns out indispensable to put the train back on the tracks knowing for sure that the Chinese civilization does not need made up stories because it deserved to appear for a long time among the great civilizations of humanity. It is the ancestors of the Luo Yue that taught the folks from the North the culture of rice and not the other way around as has been written in a large number of Chinese and Vietnamese historic documents. The time has come to give the homage to our ancestors, the Yue, who because of their peaceful nature were forced to be wiped off in front of the use of force in the turmoil of history.

Inheriting a glorious past, embroiled in successive fratricidal and colonial wars and mired in corruption, Luo Yue’s Vietnam needs to pull itself together because it does not deserve to be one of the poorest countries in the world. It is time for it to follow in the footsteps of its ancestors and do better than them.