Since the beginning of time, the Vietnamese were used to living in an inhospitable environment. Their living conditions were very hard and nature is extremely tough and pitiless. They must learn how to live with wild animals, tricking them and beating them. From that came a number of prejudices and superstitions. It is found in popular songs not only a kind of experience lived by the Vietnamese in the animal reign but also a certain philosoply sometimes just and simple. Based on observations and behavior found in the animal world, they succeeded in enriching their popular songs giving them a more invigorating, humorous, attractive and moralizing characteristic. Without referring to these wild and familiar creatures, popular songs would probably have lost their attractiveness they have kept so far. The following example indisputably illustrates this agreement borrowed from the animal reign:

Chim khôn tiếc lông

Người khôn tiếc lời

An intelligent bird keeps it feathers,

Wise people do not waste their words.

Without alluding to the bird and its feathers, the second verse would probably not have its significant range of subtlety. Likewise, in a concise manner, the following proverb depicts and sums up everything :

Một con quạ, đồn ba con ác

Rumor turns a crow into three magpies

to refer to a brag.

Instead of using the word « quạ » to mean a crow, the word « ác » is prefereed because in Chinese-Vietnamese dictionary « ac » also means evil. By its pronunciation and connotation, it brings us into inescapably thinking of something harmful while keeping intact the significant range of the proverb. It is not surprising to see a crow here because it is the bird the Vietnamese hate and spit upon. Thanks to this detestable bird, the degree of importance can be measured given the reflection contained in the proverb.

By using popular songs, proverbs and legends, the Vietnamese have on several occasions shown their opinion on the animal reign. Certain wild animals are respected and sacred, others are not. Having to share the same environment with wild animals, they do not hesitate to associate them in their daily life, to reserve a particular regard to each of them, and to give them a hierarchic classification to the image of the Vietnamese society. All that has unquestionably been dictated by their live observations and experiences that with the flow of time become transmitted from generation to generation and anchored intimately in their mind.

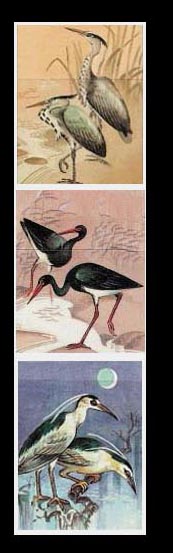

The egret is a kind of heron that we used to see in company with the peasants on rice fields. Leaning on its long legs, she ceaselessly tiptoes quietly there in search of food or advances seriously in long strides.

This picture is not foreign to the impression the Vietnamese give to this creature. Is she the mysterious wader that we see carved on the bronze drums of Ðồng Sơn. In anyway, she is the symbol of purity and sacrifice. That is what we found in the following popular song:

Con cò lặn lội bờ ao

Tôi có tội nào ông sáo với măng

Có sào thì sáo nước trong

Chớ sáo nước đục đau lòng cò con !

The egret searching for food at night time

Landing on a weak branch, she tumbles in the pond.

Sir, please fish me out of here,

If I am unfaithful you may want to cook me with bamboo shoot.

Cooking me you have to use clear water,

Don’t use dirty water, it hurt the feeling of this tiny egret!

She is also evoked in another song, identifying herself to a Vietnamese woman:

Con cò lặn lội bờ sông,

Gánh gạo đưa chồng tiếng khóc nĩ non,

Nàng về nuôi cái cùng con,

Ðể anh đi trãy nước non Cao-Bằng.

Like an egret wading at the river side,

Hauling rice accompanying her husband she sobs:

I am returning home to take care of mother and children,

So you may rest assured trekking the Cao Bang rugged terrain.

The egret is appreciated such that in some regions of Vietnam it is given the title of nobility: Mister Farmer ( Ong Nông ). This respect may probably be due to its beautiful plumage and its imposing look in the middle of the rice fields. Being alongside with it, the peasants consider it as a companion that know how to participate in their daily occupations. The same for the heron ( vạc) who is synonymous with elegance and longevity. We use to say : Cưỡi hạc chầu trời to allude to an old person who passes away. On the contrary, a crow is seen unfavorably. Because of its black feathers, this creature is synonymous with misfortune. Its sudden appearance in front of the house or on the way calls for a bad omen. To blame the public for having an erroneous opinion, we borrow this proverb:

Quạ ăn dưa bắt cò phơi nắng

Nghĩ lại sự đời quạ trắng cò đen

The crow eats the melon but the egret is punished by having to stay in the sun

Reflecting on life gives the feeling that the crow is white and the egret is black.

Likewise, the bear is not so much favorite. It is called « Cha Cụ » or « Cha Gấu ( father bear ). The term « Cha » is very derogatory. It is seen in this designation a contemptible and ridiculous character. The allusion is probably made to show someone who, even he is the head of the family, does not live up to his role and deserve a particular regard. Would it have anything to do with the weight and slowliness of this plantigrade in its gait? In spite of that unjustified appellation, the bear is not as unfortunate as other creatures against whom the discrimination is even more visible. The pelican (chim bồ nông ), despite its respectable size and its extensible pouch where fish are stored for feeding its chicks, receives only a little title « thằng bè » ( or the heavy guy ). The teal ( con le le ) is often called » thằng bồng » while the kingfisher ( chim bói cá ) is often labeled as « thằng chài » ( the one who fishes with a net ).

For the latter, there is no doubt on the choice of this attribution which is probably tied to the agility of this bird in its dive and capture of fish. The term « thằng » is intentinonally used to show a state of inferiority of the creature or the person in question in relation with other species or individuals. It is also the case of the loon that is often called « thằng cộc » thằng cha cộc ». Some birds are bluntly feminized because we grant them the title « mệ »( grandma ) or « mạ » ( mother ). It is the case of the heron ( con diệc ) that we use to called « mạ diệc » ( mother heron ). Another creature of the same family as the heron, the squacco heron, receives the title « mệ thợm » ( the crabeating gossiper ).

Some creatures are considered as those who come from Heaven living in open sky. The word « Trời » ( or sky, heaven ) is found in their names. It is the case of « vịt trời » ( wild duck ) « ngỗng trời »( wild goose ) or ngựa trời ( religious mantis ) or horse from the sky.On the other hand, the Vietnamese think that other creatures can capture their thoughts, and out of fear and reprisals they pay respect to those creatures in order to escape their mortal traps. That is why the word « Thiêng » is used to depict supernatural creatures.

It is the case of the little mouse ( con chuột ). They dare not call it by its name despite its minuscule size. They prefer to give it the tittle » Ông Thiêng » ( or Mister Sacred ) because it is capable of carrying out reprisals and of knowing all the secrets and privacy in their house. Likewise, the sparrow ( chim se sẽ ) receives the same honor as the mouse’s. By its supernatural force the sparrow can escape from the trap and cause big damages by destroying their rice stocks. The ant takes part in the supernatural creatures the same way as the elephant ( ông voi) and the tiger ( ông cọp, ông Ba Mươi ). The latter two have the capability of listening to their conversations, which makes them known as « ông Thính » ( Mister Listener ).The ant takes part in the supernatural creatures the same way as the elephant ( ông voi) and the tiger ( ông cọp, ông Ba Mươi ) . The latter two have the capability of listening to their conversations, which makes them known as « ông Thính » ( Mister Listener ).It is attributed to the tiger the aptitude of bearing on its shoulder the soul of its victim. This one, wandering and known under the term « Ma » ( ghost ) compels the tiger to return to where the victim lived in search for offerings. It is the way to interpret the return of the tiger around the area where the victim was devoured in order to catch another prey.

That is why it is very necessary to find at any costs what belongs to the victim, burn it together with a double made of paper and that of the tiger and bury them carefully in order to return the soul indefinitely into the tomb. It is ceaselessly believed that the tiger’s whiskers possess a character harmful to health. That is why in order to avoid the damages that may be caused by these whiskers, they decide to burn them immediately at the capture of this tiger.

For most Vietnamese, the tiger is sometimes feared and revered. For fear of reprisals, they keep not only signs of respect but also temples and altars dedicated in its honor and scattered here and there in the forest. Even before killing it after capturing it, they do not even forget to give it the last homage in holding a preliminary ceremony. They use to compare themselves with the tiger by means of the following maxim:

Hùm chết để da, người chết để tiếng.

Le tigre mort laisse sa peau et l’homme décédé sa réputation.

and to grant the king of the animals an irreproachable veneration. Despite that, the animal the most preferred remains the dragon. This one is part of the four animals with supernatural power ( Tứ Linh ) ( the dragon ( rồng, long ) , the unicorn ( lân ), the turtle ( quy, rùa ) and the phoenix ( loan, phượng, phụng ) ) and occupies the first place. It is the emblematic animal traditionally chosen by the king on his clothes. It appears as a key element of the Vietnamese mythology. All Vietnamese strongly believe they are descendents of this fabulous and mythical animal. The unicorn is synonymous with happiness. As for the turtle, it is not only the symbol of longevity but also that of the transfer of spiritual value in the Vietnamese tradition. Its presence has been mentioned many times in the history of Vietnam by means of legends. ( The magic crossbow offered by the golden turtle god to king An Dương Vương in his struggle against Chinese general Triệu Ðà ( Zhao Tuo ), the return of the sword to the turtle god by the future king Lê Lợiafter his shining victory over Chinese invaders, the Ming at the Hoan Kiem lake). The phoenix always identifies with beauty. This mythical bird is often referred to in marriage. Someone having the profile of the son of Heaven ( tướng thiên tử ) is depicted as having the nose of the dragon and the eyes of the phoenix ( mũi rồng mắt phượng).

To separate the lovers, it is said: Chia loan rẽ phượng. Loan is the meaning of the female phoenix while phượng is used for the male one.

Besides these mythical animals, there is another one often spoken of in Vietnamese annals and that is the water dragon ( con thuồng luồng ). It is a serpent resembling an eel, which has been described in P. Genibrel’s dictionary. To protect themselves against the water dragons, the Vietnamese used to tattoo their body so that they would not look different and be killed by these animals when they go fishing. This custom disappeared only during the reign of Trần Anh Tôn who himself renounced this practice. The water dragon is also the subject of the following proverb:

Thuồng luồng không ở cạn

The water dragon don’t live in the places where there is no water.

to mean that people of quality do not associate with lower people.

In the coastal regions, the animal the most revered remains the whale (or cá voi, cá ông). It is not surprising to see in each village along the coast, springing up an altar dedicated for this mammal. The profound attachment to this cetacean from Vietnamese fishermen is due to a great number of blessings it brought them.

Altar reserved for the whale.( Poulo Cham)

In Vietnam, attention is made to precursor of natural phenomena seen in the behavior of wild creatures. Out of the roar of a tiger in search for food, the dry and staccato sound made by a deer or the squeal of a squirrel, a change of weather could be forecast (incoming wind or rain from the north). The hooting of a rooster of pagoda ( chim bìm bịp ) is a sign of an incoming flood. Seeing the ants building their big earthen nests in a hurry in the trees along the riverside, it would be possible to predict that a rise in water level is imminent. The unjustified song of a rooster predicts a bad news. The nibbling of mice in the house is not a good omen at all. The hooting of an owl near the house announces the imminent death of the sick if any in it. The drop of a spider from the ceiling is a mark of an infidelity in the household. The flight of a dragonfly on the ground level signals the imminent arrival of sunshine or rain. It is said in the following little saying:

Chuổn chuổn bay thấp thì mưa

Bay cao thì nắng, bay vừa thì râm

The dragonfly flying low brings rain

Flying high gives sunshine, flying average height predicts shadow.

A scientific explanation can be provided to that saying because the dragonfly possesses a pouch of water enabling it to regulate the altitude of its flight in function with air humidity. It is the application of the Archimedean push in air that we find in this behavior.

This superstition has been exploited in the past with ingenuity by a great number of Vietnamese leaders to consolidate their legitimacy in the conquest of power. It becomes a formidable and efficient weapon in the struggles against foreign invaders. It can be said that it was at the time what we have now with psychological warfare. The credulity has been put in evidence several times in the history of Vietnam. To facilitate access to the throne of the young virtuous Lý Công Uẩn, the future king of the Lý dynasty, the erudite monk Vạn Hạnh decided to mark discreetly the word » thiên tử » ( son of Heaven ) on the back of a white dog in the village Cổ Pháp and spreaded the rumor that in the current year of the Dog, there will be a new king born under the sign of the Dog to bring peace to people. That was why people did not contest the legitimacy of Lý Công Uẩn the day he took power and ascended the throne in the year of the Dog ( Canh Tuất 1010 ) under the pressure of Ðào Cam Mộc and his close relations led by monk Vạn Hạnh because people thought everything was decided in advance and that he was sent by Heaven to become king and that he was born in the year of the Dog (Giap Tuat) in 974. To shelter the capital from the caprices of the Red river, Lý Công Uẩn, heeding the advice of geomancers, intended to move the capital to Thăng Long ( or later Hà Nội). For this moving, it was necessary to make people believe that he had seen in his dream a golden dragon flying over this locality. That would help him neutralize peacefully any ideas of contestation and revolt. Likewise, several centuries later, it is not surprising to see the building of a fantastic story of the legend on the character of Lê Lợi, a rich Mường farmer at Lam Sơn in the goal of unifying all the Vietnamese people facing their destiny and of stopping all claims of submission in the struggle against Chinese invaders ( the Ming ). It was also the resistance led by a Vietnamese of Muong origin for the first time in the history of Việtnam. It was successful to make people believe that before Lê Lợi’s birth, there was a black tiger roaming around his village. Since his birth, the tiger was no longer seen in the area. It was attributed to Lê Lợi the reincarnation of that king of animals. It was Nguyễn Trãi, his political and military counsel that described it in his work « Lam Sơn Thục Lục using the following terms:

Vua Lê vai tả có bảy nốt ruồi, long lá đầy người, tiếng như chuông lớn, ngồi như hổ ….

King Lê has 7 moles on his right shoulder, a hairy body, a voice that sounds like a big bell, a look like a tiger when seated.

It was also Nguyen Trai’s clever idea to spread for several months the following message written with toothpicks and honey on leaves that people found nibbled by ants:

Lê Lợi vì dân, Nguyễn Trãi vì thân

Lê Lợi for the people, Nguyễn Trãi for Lê Lợi

in the goal of showing the people that it was Heaven’s will and that Le Loi was designated as the sole and legitimate heir in the struggle against the Ming invaders.

To make disappear the visible affliction of a great number of people before the fate reserved for Gia Long’s foes, especially the family of emperor Quang Trung ( beheading king Cảnh Thinh, exhuming his tomb, torturing by means of elephant stamping on all his people and relatives ) and to legitimize his grab of power, many of legends around Gia Long have been brought into daylight. First is the story of encounter with his eunuch general Lê Văn Duyệt. This one, known by his courage and strength, having up until then led a hidden and reserved life with his mother in a remote corner of South Vietnam, did not hesitate to kill anyone who dared disturb him. Having known this motto and been pursued relentlessly by the Tây Sơn ( the Peasants of the West ), Nguyễn Ánh, the future emperor Gia Long decided to go see him and make friend with him. With his lieutenant Nguyễn Văn Thành, he found his house but Lê Văn Duyệt was absent at the moment. His mother invited them for lunch but advised them go withdraw immediately because she knew well the character of her son. Seeing the strangers in his house, he would not hesitate to kill them. Facing Nguyen Anh’s resolution to see her son, she was obliged to let them stay overnight. On his returning home, Le Van Duyet was annoyed by the presence of strangers in his home. But he noticed hat the young man was surrounded by a snake whose head leaned on his chest. Troubled by this protection, he timidly asked his mother: Who is the person protected by the snake? Surprised by his question, she went to the room where Nguyen Anh was sleeping. She found no snake. Only Lê Văn Duyệt had seen that scene. For him there is no doubt that he was face to face with the person uncommon and under divine protection. He went to wake him up and asked him of the news. Lê Văn Duyệt became from that day one of his best and brilliant faithful in the conquest of power. According to the French erudite Léopold Cadière, the fabulous animal resembling the dragon found on Gia Long’s imperial costume or on the stage of his throne would probably evoke the snake’s protection that Nguyen Anh benefited during his years of vicissitude. Another time when he had to take refuge on the Phú Quốc island, Nguyen Anh was almost captured by the Tay Son if his boat was not held back and hampered by crocodiles. Intrigued by this omen, he knelt at the front of his boat and called upon Heaven:

If the enemies are hanging a trap at the mouth of river Ông Ðốc , please let me know by making disappear and reappear these crocodiles three times at once, if not, let me go now because time is very important for me.

Effectively, the disappearance and reappearance of the reptiles took place three time at once. Witnessing this unusual phenomenon responding to his wish, he did not want to go. To make sure of the presence of the enemies, a scout was sent out immediately. There was no more doubt that the enemies were waiting for him outnumbered on that day. If we do not know whether Nguyen Anh were under divine protected, then by means of historical stories we notice that he was a young prince, very courageous and intrepid. He was once chased by his enemies. He was compelled to swim across a river despite a great number of crocodiles. He had to resort to a buffalo to wade at the riverside in order to make the crossing.

The Vietnamese man is born with this belief. Without it, it would appear hard for him to overcome his daily life difficulties encountered in his inhospitable environment where fatality is in place. If superstition bears a certain image of pusillanimity, it remains nevertheless a effective weapon that the Vietnamese man does not miss an occasion to use in forging his destiny and purpose. He does not let himself being dragged too much into Cartesian mind to refute what belongs to the heritage of beliefs of his people.