English version

Vietnamese version

La découverte du site Hemudu (Zhejiang) en 1973 fut un grand évènement pour les archéologues chinois car ce site datant plus de 5000 ans témoigne de la trace de la plus ancienne civilisation du riz trouvée jusque là dans le monde. On y a trouvé aussi les restes d’un habitat lacustre en bois monté sur pilotis, un type de construction bien différent des maisons en terre de la Chine du Nord. La population qui vivait là était caractérisée par des traits à la fois mongoloïdes et australo-négroïdes. Comme Zhejiang fait partie des plus belles provinces de la Chine du Sud depuis longtemps, on ne cesse pas d’attribuer aux Chinois cette fameuse civilisation bien qu’on sache que le berceau de leur civilisation est lié étroitement au bassin du fleuve Jaune (ou Huang He) (Hoàng Hà) dont Anyang est le cœur antique. On ne peut pas nier que leur civilisation a trouvé toute sa quintessence dans les cultures néolithiques de Yang-Shao (province de Henan) (5000 ans av J.C.) et Longshan ( province de Shandong ) ( 2500 ans av J.C. ) identifiées respectivement par le Suédois Johan G. Andersson en 1921 et par le père de l’archéologie chinoise Li Ji quelques années plus tard. Grâce aux travaux d’analyse phylogénétique de l’équipe américaine dirigée par le professeur J.Y. Chu de l’université de Texas publiés en Juillet 1998 dans la Revue de l’Académie des Sciences américaine et groupés sous le titre « Genetic Relationship of Population in China » (1) , on a commencé à avoir une idée précise sur l’origine du peuple chinois.

On a relevé deux points importants dans ces travaux:

- 1°) Il est clair que l’évidence génétique ne peut pas soutenir une indépendance originale des Homo -sapiens en Chine. Les ancêtres des populations vivant actuellement dans l’Est de la Chine venaient de l’Asie du Sud Est.

- 2°) Désormais, il est probablement sûr de conclure que les gens « modernes » originaires d’Afrique constituent en grande partie le capital génétique trouvé couramment dans l’Asie de l’Est.

Dans sa conclusion, le professeur J.Y. Chu a reconnu qu’il est probable que les ancêtres des populations parlant des langues altaïques ( ou des Han ) étaient issus de la population de l’Asie du Sud Est et des peuplades venant de l’Asie centrale et de l’Europe.

Cette découverte n’a pas remis en cause ce qu’a proposé il y a quelques années auparavant le professeur d’anthropologie Wilhelm G. Solheim II de l’université Hawaii dans son ouvrage intitulé Une nouvelle lumière dans un passé oublié.(2) Pour cet anthropologue, il n’y avait pas de doute que la culture de Hòa Bình ( 15000 ans avant J.C. ) découverte en 1922 par l’archéologue français Madeleine Colani dans un village proche de la province Hòa Bình du Vietnam avait été la base de la naissance et de l’évolution future des cultures néolithiques de Yang-Shao (Ngưỡng Thiều) et de Longshan (Long Sơn) trouvées dans le Nord de la Chine. Le physicien britannique Stephen Oppenheimer était allé au delà de ce qui n’était pas pensé jusque-là en démontrant dans sa démarche logique et scientifique que le berceau de la civilisation de l’humanité était en Asie du Sud Est dans son ouvrage intitulé Eden dans l’Est: le continent noyé de l’Asie du Sud Est.

Il y a conclu qu’en se basant sur les preuves géologiques trouvées au fond de la mer de l’Est (Biển Đông) et sur les méthodes de datation effectuées avec C-14 sur la nourriture ( patate douce, taro, riz, céréales etc. ) retrouvée en Asie du Sud Est ( Non Nok Tha, Sa Kai ( Thailande ), Phùng Nguyên, Ðồng Ðậu (Vietnam), Indonésie ), un grand déluge avait eu lieu et avait obligé les gens de cette région qui, contrairement à ce que les archéologues occidentaux avaient décrit comme des gens vivant de pêche, de chasse et de cueillette, étaient les premiers sachant maîtriser parfaitement la riziculture et l’agriculture, à émigrer dans tous les azimuts ( soit vers le Sud en Océanie, soit vers l’Est dans le Pacifique , soit vers l’Ouest en Inde ou soit vers le Nord en Chine ) pour leur subsistance. Ces gens étaient devenus les semences des grandes et brillantes civilisations trouvées plus tard en Inde, en Mésopotamie, en Egypte et en Méditerranée.

De cette constatation archéologique et scientifique, on est amené à poser des questions sur tout ce qui a été rapporté et falsifié par l’histoire dans cette région du monde et enseigné jusque-là aux Vietnamiens. Peut-on ignorer encore longtemps ces découvertes scientifiques ? Peut-on continuer à croire encore aux écrits chinois (Hậu Hán Thư par exemple ) dans lesquels on a imputé aux préfets chinois Tích Quang (Si Kouang) et Nhâm Diên (Ren Yan) le soin d’apprendre aux ancêtres des Vietnamiens la façon de s’habiller et l’usage de la charrue qu’ils ne connaissent pas au premier siècle de notre ère? Comment ne connaissent-ils pas la riziculture, les descendants légitimes du roi Shennong (Thần Nông) (3), lorsqu’on sait que ce dernier était un spécialiste dans le domaine agraire? Personne n’ose relever cette contradiction.

Shennong (Thần Nông)

On ne se pose même pas des questions sur ce que les gens du Nord ont donné à ce héros divin comme surnom Yandi (Viêm Ðế) ( roi du pays chaud des Bai Yue ) (3). S’agit -il de leur façon de se référer au roi de la région du Sud car à l’époque des Zhou, le territoire des Yue était connu sous le nom Viêm Bang? Est-il possible aux gens nomades du Nord d’origine turco-mongole, les ancêtres des Han et aux gens du Sud, les Yue d’avoir les mêmes ancêtres? S’agit-il encore d’une pure affabulation édifiée à la gloire des conquérants et destinée à légitimer leur politique d’assimilation?

Toutes les traces des autres peuples, les « Barbares », ont été effacées lors de leur passage. La conquête du continent chinois a commencé aux confins du lœss et de la Grande Plaine et a existé près de quatre millénaires. C’est ce qu’a noté l’érudit français René Grousset dans son ouvrage « Histoire de la Chine » en parlant de l’expansion d’une race de rudes pionniers chinois de la Grande Plaine .

Face à leur brillante civilisation, peu de gens y compris les Européens lors de leur arrivée en Asie ont osé mettre en doute ce qui a été dit jusque-là dans les annales chinoises et vietnamiennes et penser à l’existence même d’une autre civilisation que les dominateurs ont réussi à accaparer et à effacer sur le territoire soumis du peuple Bai Yue. Le nom de l’Indochine a déjà reflété en grande partie cette attitude car pour un grand nombre de gens, il n’y a que deux civilisations méritant d’être citées en Asie: celles de l’Inde et de la Chine. Il est regrettable de constater aussi la même méprise commise par certains historiens vietnamiens imprégnés par la culture chinoise dans leur ouvrage historique. A force d’être endoctrinés par la politique de colonisation des gens du Nord, un certain nombre de Vietnamiens continuent à oublier notre origine et à penser aujourd’hui que nous sommes issus des Chinois. Ceux-ci n’hésitaient pas à mettre en marche leur politique d’assimilation et d’annexion dans les territoires qu’ils avaient réussi à conquérir depuis la création de leur nation. Le succès de la sinisation des Han était visible au fil des siècles lors de leur contact avec d’autres peuples « barbares » . Le processus ne dut pas être différent de celui qui a marqué leur empiétement au XIXème siècle sur la « terre des herbes mongole » et au XXème sur la forêt mandchourienne.

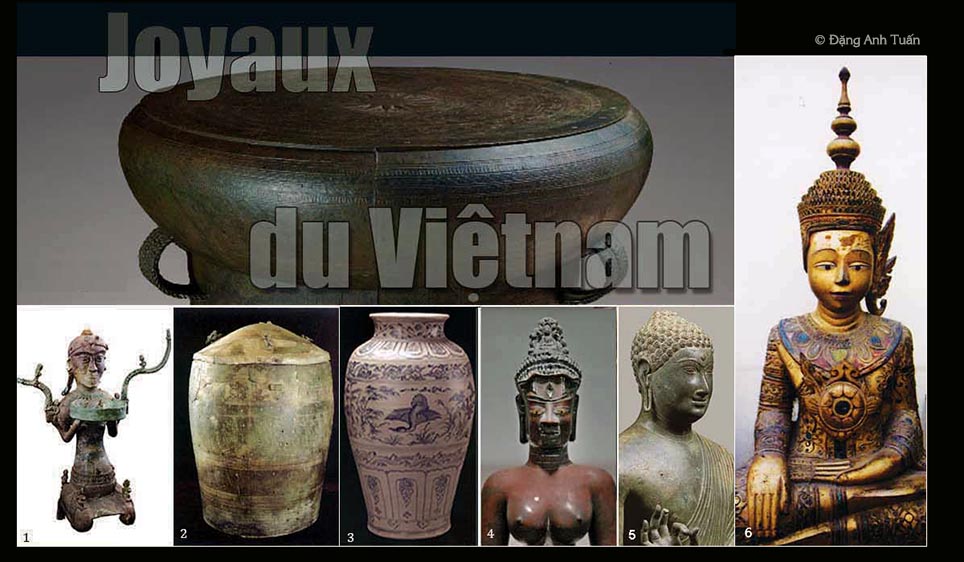

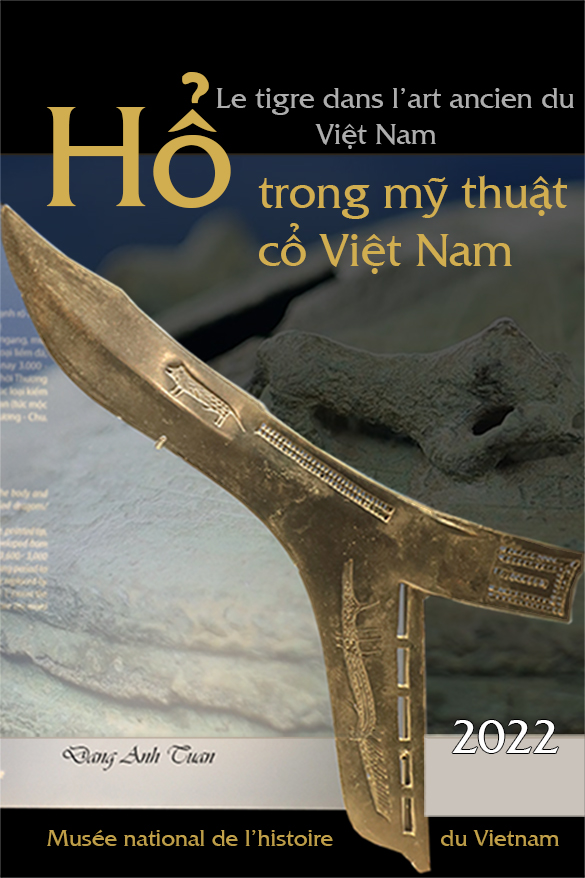

On ne réfute pas à leur brillante civilisation d’avoir un impact indéniable sur le développement de la culture vietnamienne durant leur longue domination mais on ne peut pas oublier de reconnaître que les ancêtres des Vietnamiens, les Luo Yue (ou Lạc Việt) ont eu leur propre culture, celle de Bai Yue. Ils étaient les seuls survivants de ce peuple à ne pas être sinisés dans les tourmentes de l’histoire. Ils étaient les héritiers légitimes du peuple Bai Yue et de sa civilisation agricole. Les tambours en bronze de Ðồng Sơn ont témoigné de leur légitimité car on a trouvé sur ces objets les motifs de décoration retraçant leurs activités agricoles et maritimes de cette brillante époque avant l’arrivée des Chinois sur leur territoire ( Kiao Tche ou Giao Chỉ en vietnamien ).

On sait maintenant que la civilisation agricole de Hemudu a donné naissance à la culture de Bai Yue (ou Bách Việt en vietnamien). Le terme Bai Yue signifiant littéralement les Cent Yue, a été employé par les Chinois pour désigner toutes les tribus croyant appartenir à un groupe, les Yue. Selon l’écrivain talentueux vietnamien Bình Nguyên Lộc, l’outil employé fréquemment par les Yue est la hache (cái rìu en vietnamien) trouvée sous diverses formes et fabriquée avec des matériaux différents (pierre, fer ou bronze). C’est pour cette raison qu’au moment du contact avec les gens nomades du Nord d’origine turco-mongole, les ancêtres des Han (ou Chinois), ils étaient appelés par ces derniers, sous le nom « les Yue », les gens ayant l’habitude de se servir de la hache. Celle-ci prit à cette époque la forme suivante:

et servit de modèle de représentation dans l’écriture chinoise par le pictogramme.![]() Celui-ci continua à figurer intégralement dans le mot Yue auquel on ajoute aussi le radical mễ (米) riz ou gạo en vietnamien) pour désigner les riziculteurs à l’époque de Confucius. De nos jours, dans le mot Yue 越, outre le radical « Tẩu (走) outrepasser ou en vietnamien vượt ) », la hache continue à être représentée par le pictogramme 戉 modifié incessamment au fil des années. Le mot Yue provient peut-être phonétiquement du phonème Yit employé par la tribu Mường pour désigner la hache. Il est important de rappeler que la tribu Mường est celle ayant les mêmes origines que la tribu Luo Yue (ou Lạc Việt) dont les Vietnamiens sont issus. (Les rois illustres vietnamiens Lê Ðại Hành , Lê Lợi étant des Mường). Récemment, l’archéologue et chercheuse du CNRS, Corinne Debaine-Francfort a parlé de l’utilisation des haches cérémonielles yue par les Chinois dans le sacrifice d’humains ou d’animaux, dans son ouvrage intitulé « La redécouverte de la Chine ancienne » (Editeur Gallimard, 1998). Le sage Confucius avait l’occasion de parler du peuple Bai Yue dans les entretiens qu’il a eus avec ses disciples.

Celui-ci continua à figurer intégralement dans le mot Yue auquel on ajoute aussi le radical mễ (米) riz ou gạo en vietnamien) pour désigner les riziculteurs à l’époque de Confucius. De nos jours, dans le mot Yue 越, outre le radical « Tẩu (走) outrepasser ou en vietnamien vượt ) », la hache continue à être représentée par le pictogramme 戉 modifié incessamment au fil des années. Le mot Yue provient peut-être phonétiquement du phonème Yit employé par la tribu Mường pour désigner la hache. Il est important de rappeler que la tribu Mường est celle ayant les mêmes origines que la tribu Luo Yue (ou Lạc Việt) dont les Vietnamiens sont issus. (Les rois illustres vietnamiens Lê Ðại Hành , Lê Lợi étant des Mường). Récemment, l’archéologue et chercheuse du CNRS, Corinne Debaine-Francfort a parlé de l’utilisation des haches cérémonielles yue par les Chinois dans le sacrifice d’humains ou d’animaux, dans son ouvrage intitulé « La redécouverte de la Chine ancienne » (Editeur Gallimard, 1998). Le sage Confucius avait l’occasion de parler du peuple Bai Yue dans les entretiens qu’il a eus avec ses disciples.

Le peuple Bai Yue vivant dans le sud du fleuve Yang Tsé (Dương Tử Giang) a un mode de vie, un langage, des traditions, des mœurs et une nourriture spécifique … Ils se consacrent à la riziculture et se distinguent des nôtres habitués à cultiver le millet et le blé. Ils boivent de l’eau provenant d’une sorte de plante cueillie dans la forêt et connue sous le nom « thé ». Ils aiment danser, travailler tout en chantant et alterner des répliques dans les chants. Ils se déguisent souvent dans la danse avec les feuilles des plantes. Il faut éviter de les imiter . (Xướng ca vô loại).

L’influence confucianiste n’est pas étrangère au préjugé que les parents vietnamiens continuent à entretenir encore aujourd’hui lorsque leurs enfants s’adonnent un peu trop aux activités musicales ou théâtrales. C’est dans cet esprit confucéen qu’on les voit d’un mauvais œil. Mais c’est aussi l’attitude adoptée par les gouverneurs chinois en interdisant aux Vietnamiens d’avoir des manifestations musicales dans les cérémonies et les festivités durant la période de leur longue domination.

L’historien chinois Si Ma Qian (Tư Mã Thiên) avait l’occasion de parler de ces Yue dans ses Mémoires historiques (Sử Ký Tư Mã Thiên) lorsqu’il a retracé la vie du seigneur illustre Gou Jian (Câu Tiễn), prince des Yue pour sa patience incommensurable face au seigneur ennemi Fu Chai (Phù Sai), roi de la principauté de Wu (Ngô) à l’époque des Printemps et Automnes. Après sa mort, son royaume fut absorbé complètement en 332 avant J.C. par le royaume de Chu (Sở Quốc) qui fut annexé à son tour plus tard par Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng) lors de l’unification de la Chine. Il est important de souligner que le site de Hemudu se trouve dans le royaume Yue de Gou Jian.(Zhejiang).

Parmi les groupes partageant la même culture de Bai Yue , on trouve les Yang Yue, les Nan Yue (Nam Việt), les Lu Yue, Les Xi Ou, Les Ou Yue, les Luo Yue (Lạc Việt , les Gan Yue, les Min Yue (Mân Việt), les Yi Yue, les Yue Shang etc. Ils vivaient au sud du bassin du fleuve bleu , de Zhejiang (Chiết Giang) jusqu’au Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ)(le Nord du Vietnam d’aujourd’hui). On retrouve dans cette aire de répartition les provinces actuelles de la Chine du Sud: Foujian (Phúc Kiến), Hunan (Hồ Nam), Guizhou (Qúi Châu), Guangdong (Quảng Ðông), Jiangxi, Guangxi (Quảng Tây) et Yunnan (Vân Nam).

Les Bai Yue étaient probablement les héritiers de la culture Hoà Bình . Ils étaient un peuple d’agriculteurs avertis: ils cultivaient le riz en brûlis et en champ inondé et élevaient buffles et porcs. Ils vivaient aussi de la chasse et de la pêche. Ils avaient coutume de se tatouer le corps pour se protéger contre les attaques des dragons d’eau (con thuồng luồng). En s’appuyant sur les Mémoires Historiques de Si Ma Qian, l’érudit français Léonard Aurousseau a évoqué la coutume des ancêtres de Goujian ( roi des Yue de l’Est) de peindre leurs corps de dragons ou d’autres bêtes aquatiques comme celle trouvée chez les Yue du Sud.

Ils portaient les cheveux longs en chignon et soutenus par un turban. D’après certains textes vietnamiens, ils avaient des cheveux courts pour faciliter leur marche dans les forêts des montagnes. Leurs vêtements étaient confectionnés avec les fibres végétales. Leurs maisons étaient surélevées pour éviter les attaques des bêtes sauvages. Ils se servaient de tambours en bronze comme d’objets rituels utilisés pour les cérémonies d’invocation à la pluie ou comme un emblème de pouvoir utilisé en cas de besoins pour appeler les guerriers au combat. « Les Giao Chỉ ont possédé un sacré instrument : le tambour en bronze. En écoutant la voix du tambour, ils étaient tellement enthousiastes au moment de la guerre etc. », c’est ce qu’on a trouvé dans le premier volume de l’écrit chinois « Hậu Hán Thư (L’écrit de Hán postérieur) . Leurs guerriers étaient vêtus d’un simple pagne et armés de longues lances ornées de plumes. Ils étaient aussi des hardis navigateurs qui, sur leurs longues pirogues, sillonnèrent toute la Mer de l’Est (Biển Đông) et au delà une partie des mers australes. Malgré leur haute technicité et leur maîtrise parfaite en matière d’agriculture et de riziculture, ils étaient un peuple très pacifique. Lire la suite (2ème partie)

(1) Volume 95, issue 20, 1763-1768, 29 July , 1998

(2) National Geographic, Vol 139, no 3

(3) Kinh Dương Vương, étant le père de l’ancêtre des Vietnamiens, Lạc Long Quân et l’arrière petit-fils du roi Shen Nong.