Version française

English version

Văn hóa Phùng Nguyên

Tìm về cội nguồn của dân tộc Việt.

Phùng Nguyên là tên một làng ở xã Phùng Nguyên, huyện Lâm Thao, tỉnh Phú Thọ, nơi mà tìm ra các di chỉ của nền văn hóa nầy. Được biết ngày nay văn hoá Đồng Sơn là văn hóa của người Lạc Việt tức là tổ tiên của người Việt hiện đại qua các cuộc khai quật những địa điểm quan trọng có nhiều tầng văn hóa dày thì các nhà khảo cổ phát hiện không có lớp trống nào ngăn cách chẳng hạn như ở địa điểm Đình Chàng thuộc xã Đồng Anh (Hànội). Nơi nầy ở trong di chỉ Gò Mun thì thấy có các ngôi nhà mộ của văn hóa Đồng Sơn mà dưới lớp văn hóa Gò Mun thì lại có văn hóa Đồng Đậu và Phùng Nguyên. Như vậy cho thấy không có sự phá vỡ tính liên tục giữa các văn hoá và cũng nhờ đó mà chúng ta được thấy phổ hệ Phùng Nguyên-Đồng Đậu-Gò Mun-Đồng sơn mà các nhà khảo cổ học dựng lên rất là chính xác nhất là thêm vào đó còn có sự xác nhận bằng các niên đại carbon phóng xạ. Các nền văn hoá nầy được nối tiếp nhau trong thời gian có nghĩa là từ mỗi nền văn hóa nầy được phát triển thành văn hoá tiếp theo và được phân bố ở trong vùng trung du và lưu vực sông Hồng như các tỉnh Phú Thọ, Hà Nội, Vĩnh Phúc, Bắc Ninh, Ninh Bình vân vân … mà có thể nói là vùng đất thiêng liêng cội nguồn của dân tộc Việt.

Theo giáo sư khảo cổ học Hà Văn Tấn thì các văn hóa nầy có thể phân biệt dễ dàng qua đồ gốm. Muốn biết nguồn gốc người dân Việt hiện đại chúng ta cần phải đi ngược lên đến văn hóa Phùng Nguyên cách đây chừng 4.000 năm. Đấy là thời kỳ nước ta tên là Văn Lang được cai trị bởi các vua Hùng trong truyền thuyết. Theo sự nhận xét của giáo sư Hà văn Tấn, các bộ lạc của văn hoá Phùng Nguyên là cái lõi đầu tiên trong quá trình hình thành dân tộc Việt-Mường và xây dựng nền quốc gia. Lúc đầu, các di vật Phùng Nguyên tìm thấy ở trong các cuộc khai quật đã đạt được đến mức độ rất tinh xão như ngọc, đá, gốm, xương, sừng khiến ai cũng xác định thuộc về thời kỳ giai đoạn hậu kỳ đá mới nhất là trong kỹ thuật chế tác đá và chế tác gốm nhưng về sau với sự hiện diện của một số cổ vật đồng thau được tìm thấy thì các nhà nghiên cứu như Hà Văn Tấn, Trần Quốc Vượng cũng thống nhất quan điểm cho rằng văn hóa Phùng Nguyên là khởi nguồn của thời kỳ đồ đồng tại miền Bắc Việt Nam và có ảnh hưởng về sau đến nhiều vùng Đông Nam Á qua văn hóa Đồng Sơn.

Cư dân văn hoá Phùng Nguyên có phải là người Lạc Việt, tổ tiên của người Việt (Kinh) hiện đại hay là họ chỉ là tộc Việt hay là những người từ đâu đến định cư ở vùng sông Hồng? Họ đến từ Mã Lai hay sông Dương Tử chăng? Nguồn gốc của người Việt rất mơ hồ trong lịch sử bởi vì chỉ dựa trên truyền thuyết đôi khi còn làm ta khó tin và phi lý như truyền thuyết « Lạc Long Quân-Âu Cơ » với cái bọc nở ra một trăm trứng. Đối với nhà nghiên cứu Paul Pozner [1], thuật chép sử Việt Nam đều dựa trên truyền thống lịch sử lâu dài và vĩnh cửu và được thể hiện bởi một truyền thống truyền miệng kéo dài từ thế kỷ thứ 3 đến nửa thế kỷ thứ nhất của thiên niên kỷ đâu tiên dưới hình thức các truyền thuyết lịch sử ở trong các đền thờ cúng tổ tiên.

Trăm năm bia đá thì mòn

Ngàn năm bia miệng vẫn còn trơ trơ.

Hai câu trong ca dao trên đây cũng biểu lộ được một phần nào sự khôn khéo của người dân Việt trong việc bảo vệ nền văn hóa mà họ có từ thời đại Hồng Bàng trước sự đàn áp không ngừng của Trung Hoa khi thôn tính đựơc đất nước chúng ta.

Từ việc tướng Mã Viện của nhà Đông Hán gom nhiều trống đồng và nấu chảy chúng để đúc ngựa và dâng cho Hán đế đến việc phá chùa, đốt sách, bắt bớ và lưu đày hơn 10 000 người Việt tài năng trong đó có Nguyễn An, người thiết kế Tử Cấm Thành Bắc Kinh dưới thời Vĩnh Lạc Chu Đệ (nhà Minh) thì cho ta thấy chính sách bài bản và thâm độc của người Hoa Hạ (Trung Hoa) nhầm để đồng hóa tộc Lạc Việt, một tộc duy nhất trong đại tộc Bách Việt còn có nền độc lập vững chắc cho đến ngày nay. May thay chỉ có hơn 20 năm gần đây từ 1998 nhờ các công trình nghiên cứu về phát sinh chủng loại phân tử của các nhóm khảo cứu ở Mỹ và Âu Châu nhất là có sự tiến bộ của kỹ thuật phân tích DNA trong ngành nhân học mà chúng ta có được dữ liệu trên toàn bộ gen cùng với dữ liệu về các bộ DNA một cách chính xác hơn khiến chúng ta không còn những khúc mắc lịch sử và được thấy rõ ràng hơn nguồn gốc dân Việt hiện đại.

Khi tách rời Châu Phi, cư dân cổ di cư ở khắp mọi nơi với hai làn sóng, một làn sóng di cư đi đến vùng Đông Nam Á gồm có Vietnam qua ven biển Ấn Độ vào khoảng 60.000-30.000 năm trước Công Nguyên (TCN) trước khi đến Úc Châu và đi ngược lên Bắc Mỹ qua eo Bering. Còn một làn khác đi lên đến Trung Cận Đông và Trung Á, men theo dãy núi Himalaya tới Đông Nam Á, trong đó có Việt Nam vào khoảng 30.000 năm TCN nhờ các dữ liệu di truyền được biết. Dựa trên các tài liệu nghiên cứu di truyền, một số các tác giả Việt như Cung Đình Thanh, Hà Văn Thùy, Lang Linh hay Hoàng Nguyễn đưa ra một giã thuyết vô cùng tương hợp với truyền thuyết, lịch sử cùng các cuộc khai quật trong thời gian qua ở Việt Nam.

Chính lúc thời gian ở Đông Nam Á mà người cổ (chủng cổ Mã Lai)(Indonésien) từ sự hoà hợp của hai đại chủng Mongolid và Australoid để lại dấu ấn ở lưu vực sông Hồng với nền văn hóa nổi tiếng đó là văn hóa Hòa Bình (18000-10000 TCN) mà nhà nữ khảo cổ Pháp Madeleine Colani khám phá được vào năm 1922. Đây cũng là một nền văn hoá khởi nguồn cho văn minh của người Việt cổ. Nó được lan truyền và ảnh hưởng đến các nền văn hóa đồ đá mới của Trung Hoa như văn hóa Ngưỡng Thiều (Sơn Tây) và Hồng Sơn. Nhà vật lý người Anh Stephen Oppenheimer đã có tầm nhìn xa hơn những gì người ta chưa nghĩ đến ở thời điểm đó bằng cách chứng minh bằng phương pháp khoa học và hợp lý rằng cái nôi của nền văn minh nhân loại nằm ở Đông Nam Á trong tác phẩm » Địa đàng ở phương Đông ».

Theo tài liệu nghiên cứu di truyền của McColl cùng nhóm đồng nghiệp [2] thì người Hoà Bình lúc đó có gen gần nhất với gen của người Onge sống ở trên đảo Andama và chưa có hoà huyết với các sắc dân tộc khác. Đây là loại người da đen tóc quắn, tầm vóc thấp mà ta nhận diện được với người Hoà Bình. Họ là những người đầu tiên biết rõ về kỹ thuật trồng lúa nước và nông nghiệp khác như ngũ cốc vân vân…(Hang Ma chẳng hạn) thế mà qua sự mô tả của các nhà khảo cổ phương Tây thì họ chỉ là những người sống bằng nghề đánh cá, săn bắn và hái lượm. Còn tệ hơn nửa là trong Hậu Hán Thư còn cho rằng các quan thái thú Trung Hoa Tích Quang (Si Kouang) và Nhâm Diên (Ren Yan) dạy tổ tiên ta mới biết trồng lúa. Thật là phi lý và hoang đường.

Sau đó có một trận lụt lớn đã xảy ở thời điểm 12000 năm trước khiến làm một phần lớn đất đai mà các nhóm cư dân tiền sử sinh sống như lưu vực sông Hồng đã chìm xuống dưới biển khiến buộc l òng họ phải mạo hiểm di tản khắp mọi nơi phía nam ở Châu Đại Dương, phía đông ở Thái Bình Dương hoặc phía tây ở Ấn Độ hay phía bắc ở vùng sông Dương Tử mang theo đặc trưng văn hóa Hòa Bình với di chỉ Tiên Nhân động (Xian Ren Dong) chẳng hạn ở Giang Tây (Jiangxi). Theo các công việc nghiên cứu di truyền thì họ là cư dân Đông Nam Á cổ (hay người Hoà Bình) có dừng chân ở lưu vực sông Dương Tử vì nơi nầy thuận lợi ở thời điểm đó cho việc phát triển triển trồng lúa nước. Còn có một nhóm người vẫn tiếp tục hành trình đi lên vùng Đông Á, đem theo lúa đã được họ thuần hóa (di chỉ Thượng Sơn, Shangshan) qua ngã Chiết Giang (Zhe Jiang) và kê để rồi định cư không những ở đồng bằng sông Hoàng Hà mà còn lên đến tận vùng sông Liêu (Nội Mông).

Chính họ hợp nhất ở nơi nầy vớí cư dân cổ Bắc Á, những người du mục có dấu tích ở hang Devil’s Gate thuộc vùng lãnh thổ Nga giáp ranh giới với Triều Tiên (Tây Bá Lợi Á) mà tạo ra người Mongoloid phương Bắc điển hình và văn hoá Hồng Sơn được tìm thấy từ khu Nội Mông đến Liêu Ninh. Những người Mông Cổ phương Bắc còn tiến xuống vùng sông Hoàng Hà, nơi có người Miêu tộc cư trú và gỉỏi về làm ruộng. Họ được gọi là bộ tộc « Yi ». Bởi vậy chữ tượng hình Yi 夷 được có nguồn gốc từ hình chữ người 人 có mang một cây cung 弓 Họ được nổi bật trong việc cởi ngựa bắn cung và họ rất thiện chiến. Bởi vậy họ dành thắng lợi với Hoàng Đế (Yandi) trong cuộc chiến tranh với người Miêu tộc do Xi Vưu (Chiyou) cầm đầu tại Trác Lộc (Zhuolu) ở Hà Bắc (Hebei) vào năm 2704 TCN và với Viêm Đế (Thần Nông) 3 lần khiến dẫn đến sự thành hình nền văn minh Hoa Hạ (Ngưỡng Thiều (Yangshao) và Đại Vấn Khẩu (Dawenkou)) và tạo ra chủng Mongoloïd phương Nam với cư dân cổ Đông Nam Á. Người Mongoloïd phương Nam càng ngày càng tăng số lượng và trở thành chủ thể của lưu vực Hoàng Hà từ đó mà cũng là tổ tiên của người Hán hiện đại.

Ngược lại cũng có cư dân tiền Nam Đảo và Tai-Kadai có nguồn gốc cũng từ vùng Đông Nam Á di cư lên sau và định cư sau đó ở trong vùng Sơn Đông. Rồi lại từ đó họ lại xuống định cư về sau ở vùng sông Dương Tử vào khoảng 6000 năm trước mang cả kê được tìm thấy sớm nhất ở di chỉ Tanshishan có niên đại 3500 TCN trong vùng Phúc Kiến [3] theo các dữ liệu nghiên cứu di truyền [4][5]. Người Nam Đảo thì họ tiếp tục di cư sang đảo Đài Loan và phân tán ra sau đó ở vùng Đông Nam Á hải đảo.

Ở lưu vực sông Dương Tử có sự thành hình cộng đồng tộc Việt Tai-Kadai từ sự gần gũi của các cư dân bản địa thuộc hệ ngữ Nam Á và cư dân tiền Nam Đảo, Tai-Kadai đến sau. Từ các yếu tố di truyền do sự hoà huyết giữa các cư dân bản địa và di cư mới đến với các làn sóng di cư từ Bắc Á xuống Nam Á và ngược lại qua cả nghìn năm khiến có sự thay đổi ở trong cấu trúc của gen nhất là có sự ảnh hưởng của môi trường sinh sống khiến có sự thay đổi dĩ nhiên về dáng vóc cũng như màu da và dẫn đến sự thành hình người Hoa Bắc, Hoa Nam cùng người Việt thuộc chủng Nam Á. Chủng nầy là chủng tộc hợp nhiều sắc tộc ở Đông Á. Cả tiếng nói cũng vay mượn từ việc sinh sống chung của các tộc Việt với nhau ở khu vực sông Dương Tử nên có sự xuất hiện ngữ hệ Nam Á. Các nhà ngôn ngữ học người Mỹ Mei Tsulin và Norman Jerry [6] đã xác định có 15 từ mượn từ ngữ hệ Nam Á trong các văn bản tiếng Trung Hoa dưới thời nhà Hán. Đây là trường hợp điển hình của các chữ Hán tự như từ jiang 囝 (là sông, giang trong tiếng Việt) hay từ nu 弩 (là ná trong tiếng Việt). Họ kết luận rằng có sự tiếp xúc giữa hai ngôn ngữ Trung Quốc và Nam Á ở vùng phía nam của Trung Quốc ngày nay. Chính cũng ở nơi nầy mà tộc Việt nhận thức họ khác biệt rõ ràng với các tộc du mục ở khu vực sông Hoàng Hà. Họ tự xưng họ là Yue.

Chữ « Việt (Yue (rìu)) » mà họ dùng để tự xưng họ là cư dân sống ở khu vực sông Dương Tử hay có thói quen dùng chiếc rìu để canh tác trồng trọt và tự vệ khi có sự xâm lựợc của người Hoa Hạ chớ những người nầy lúc nào vẫn xem họ là Man Di. Chính họ đã dẫn đến sự thành hình các nền văn hóa lớn như Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà. Chính nhờ những cuộc khai quật khảo cổ ở phía hạ lưu sông Dương Tử vào thập kỷ 1970 mà chúng ta được biết đến văn hóa Lương Chử. Văn hoá nầy còn tiến bộ hơn nhiều lần so với văn hoá Ngưỡng Thiều vì nó có đến 3.300 năm TCN với sự khám phá chữ tượng hình được khắc trên đá, yếm rùa, xương thú trong bói toán và cúng tế. Chữ nầy có sớm hơn Giáp cốt văn Ân Khư 2.000 năm. Được biết người cư dân Lương Chử có một lối sống định cư ổn định cùng một hệ thống tưới tiêu bằng nguồn nước lưu giữ qua kênh mương và một tổ chức xã hội cần nhiều nhân lực cho việc sản xuất và phân phối.

Có Man Di hay không nhưng ý thức dân tộc của tộc Việt được thấy rõ và được tìm thấy sớm ở trên một hiện vật của văn hóa Lương Chử vào khoảng 3300 năm TCN có ghi khắc 4 biểu tượng bằng chữ viết mà nhà nghiên cứu Trung Quốc, Đổng Sở Bình đã giải mã ý nghĩa là “Phương Việt hội thi” có thể hiểu là “Liên minh quốc gia Việt ».

Vì vậy người Hoa Hạ đã tiếp nhận cách tự nhận của người Việt để chép vào Giáp Cốt văn nhà Thương và còn dùng rìu trong việc tế lễ theo lời nhận xét của nhà khảo cổ Pháp Corinne Debaine-Francfort. Được xem là văn hóa ngọc thạch, văn hóa Lương Chử gồm có rất nhiều các đồ tạo tác từ ngọc thạch như rìu ngọc, cong, đĩa bích tế trời, ngọc tông vân vân… được phát hiện trong các ngôi mộ của tầng lớp cai trị và quý tộc còn các người nghèo thì được chôn cất với đồ gốm. Rìu ngọc vừa là lễ khí mà còn là vật biểu dương quyền lực mới chỉ bắt đầu được trông thấy ở văn hóa Lương Chử ở vùng Thái Hồ (Giang Tô, Jiangsu) trong địa bàn của nước Xích Quỷ của vua Kinh Dương Vương, thủy tỗ của tộc Việt và cha của Lạc Long Quân trong truyền thuyết. Theo nhà văn người Việt Nguyên Nguyên [7] thì Kinh Dương Vương 涇陽王 có thể dịch là vua Việt trịnh trọng. Việc truyền thuyết ghi Kinh Dương Vương lên ngôi, lập nhà nước Xích Quỷ năm 2879 TCN sau khi nhà nước Lương Chử hình thành từ 3300 năm TCN, cho thấy nước Xích Quỷ ra đời đúng vào thời kỳ sung mãn của Lương Chử. Chủ nhân của nền văn hóa nầy ghép cho vật tổ là chim và thú. Như vậy có liên hệ mật thiết đến Hồng Bàng là Chim và Rắn tức là Tiên và Rồng.

Do nước biển dâng lên cao nên tộc Việt phải dời đến vùng trung lưu của sông Dương Tử xung quanh Động Đình Hồ, nơi mà được tiếp nối bởi văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà (Shijahe) 2600-2000 năm TCN. Đây là một nền văn hóa ở cuối thời đại đồ đá ở Hồ Bắc với 1000 hiện vật được tìm thấy. Tương tự thành phố Lương Chử, thành phố Thạch Gia Hà có một hệ thống kênh mương được đào xung quanh các khu đô thị và kết nối với các con sông gần đó. Trong số các hiện vật được tìm thấy, có một hiện vật cần có sự chú ý của mọi người đó là chiếc bình gốm lại có hình một thủ lỉnh mà trên đầu có cái gù trang sức với lông chim rất phù hợp với hình người nhảy múa mặc bộ đồ bằng lông chim trên các trống đồng (Ngọc Lũ chẳng hạn) của văn hoá Đồng Sơn. Đây chính là biểu tượng của tộc Việt. Thạch Gia Hà nằm ở trong địa bàn của nước Văn Lang tộc Việt. Qua sự mô tả địa lý trong truyền thuy ết thì được bi ết nước Văn Lang thời đó có đất đai rộng lớn giáp ranh bắc đến hồ Động Đình, nam giáp nước Hồ Tôn (Chiêm Thành), đông giáp biển Nam Hải, tây đến Ba Thục (Tứ Xuyên) và có nhiều bộ tộc Việt sống rải rác từ trung lưu đến hạ lưu sông Dương Tử.

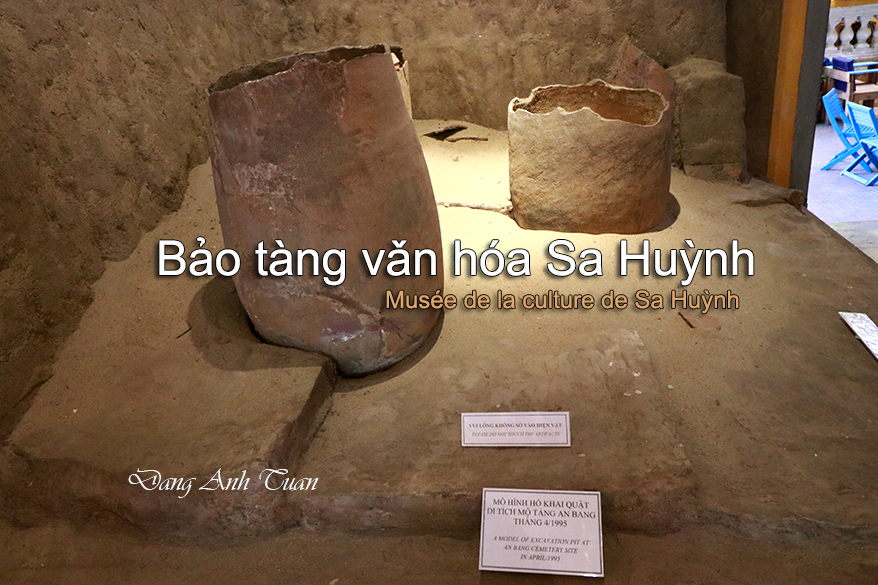

Tên Văn Lang có nguồn gốc từ tiếng Việt cổ là Blang hay Klang mà các dân tộc miền núi thường dùng để ám chỉ vật tổ, có thể đây là một loài chim nước thuộc họ chim Diệc. Có thể xem thời đó nước Văn Lang như một liên bang của các cộng đồng tộc Việt. Đây cũng là nhà nước đầu tiên của tộc Việt theo truyền thuyết trong lịch sử Việt Nam. Có một điều đáng làm ta chú ý đến là ở văn hoá Thạch Gia Hà nầy có một hiện vật được gọi là nha chương mà nó có ý nghĩa là cái răng bằng ngọc dùng để tế núi và tế sông và được phát hiện sớm nhất ở di chỉ Nhị Lý Đầu (Erlitou) thuộc văn hóa nhà Thương mà được các nhà khảo cổ công nhận hiện nay. Mà trong truyền thuyết thì có nói đến giặc Ân qua chuyện Thánh Gióng. Như vậy có sự tiếp xúc giữa nước Văn Lang với văn hóa Ân Thương phải chăng đã nói lên cái lõi sự thật của truyền thuyết nhất là tìm được một số nhà chương không ít ở hai làng cổ Phùng Nguyên và Xóm Rền, hai nơi nầy là di chỉ của văn hóa Phùng Nguyên.

Đến thời điểm 2000 TCN thì có hạn hán ở vùng trung lưu của sông Dương Tử qua các cuộc nghiên cứu khảo cổ và khí tượng khiến làm cư dân ở Thạch Gia Hà cũng như ở Lương Chử buộc lòng phải di tản vì không còn tiếp tục hoạt động trồng lúa được nửa. Dựa trên các nghiên cứu gen của Hugh McColl và các đồng nghiệp thì cư dân nông nghiệp ngữ hệ Nam Á lại di cư trở về lại Đông Nam Á cách đây 2000 năm TCN và hoà hợp một số ít với dân cư bản xứ sống hái lượm săn bắn. Liên bang của các tộc Việt ở sông Dương Tử cũng bị tan rã. Sự việc nầy làm biến mất đi hai nền văn hóa Lương Chữ và Thạch Gia Hà. Có thể xem sự tan rã nầy nó rất phù hợp với truyền thuyết Lạc Long Quân Âu Cơ lúc chia tay: 50 đứa con theo cha đi xuống đồng bằng (Lạc Việt), 50 đứa con theo mẹ Âu Cơ lên núi (Âu Việt). Được cai trị bởi các Hùng Vương, nước Văn Lang cũng bị thu hẹp lại với 15 bộ lạc từ 1879 TCN.

Còn ở châu thổ của sông Hoàng Hà thì có ba triều đại ra đời được kế tiếp nhau: Hạ (2000-1600 TCN), Ân Thương (1600-1050 TCN) và Châu (1050-221 TCN) và đánh dấu sự kết thúc của thời tiền sử và sự khởi đầu cho nền văn minh ở Trung Quốc. Còn ở lưu vực sông Dương Từ có sự thành hình nhiều tiểu quốc tộc Việt lúc đầu, rồi từ từ thôn tính lẫn nhau để thành hình các nước lớn mà chúng ta được biết qua sử Trung Hoa như nước Ngô Việt của Ngũ Tử Tư (Wu Zixu) hay nước Việt của Câu Tiễn (Goujian) ở thời Xuân Thu và Chiến Quốc (770–221 TCN) rồi sau đó bị nước Sở thuộc đại tộc Bách Việt thôn tính nhờ Ngô Khởi (Wu Qi) trước khi Tần Thủy Hoàng diệt Sở thống nhất Trung Hoa.

Tóm lại, những cư dân nông nghiệp tộc Việt lại trở về lại Đông Nam Á và châu thổ sông Hồng là những người hậu duệ của những người tiền sử từ Đông Nam Á di cư lên khu vực sông Dương Tử cách đây 12000 năm trước.

Họ là tổ tiên của người Việt hiện đại. Chính nhờ các đặc điểm nhân chủng và di truyền, phong tục tập quán và ngôn ngữ, chúng ta có quyền khẳng định giờ đây chúng ta là người Việt phương nam thuộc ngữ hệ Nam Á mặc dù chỉ còn lại ở nơi ta truyền thuyết để xác minh nguồn gốc sau 1000 năm đô hộ của người Hoa Hạ.

Version française

Culture Phùng Nguyên

À la recherche de l’origine du peuple vietnamien.

Phùng Nguyên est le nom d’un village portant le même nom dans le district de Lâm Thao de la province de Phú Thọ où se trouvent les vestiges de cette culture. On sait aujourd’hui que la culture de Đồng Sơn est la culture des Lo Yue qui sont les ancêtres des Vietnamiens d’aujourd’hui. Grâce aux fouilles archéologiques entamées dans les endroits importants ayant plusieurs couches culturelles, les archéologues vietnamiens ont découvert qu’il n’y a aucun creux les séparant comme c’est le cas du site Đình Chàng dans la commune de Đồng Anh (Hanoi). C’est à l’intérieur du site Gò Mun qu’on trouve les tombes funéraires de la culture Đồng Sơn mais sous la couche de la culture Gò Mun, il y a les cultures Đồng Đậu et Phùng Nguyên. Cela montre qu’il n’y a pas de rupture dans la continuité entre ces cultures. Grâce à cela on peut voir la généalogie Phùng Nguyên-Đồng Đậu-Gò Mun-Đồng sơn que les archéologues ont établie de manière très précise avec la confirmation de plus des datations au radiocarbone. Ces cultures se succèdent dans le temps. Cela signifie qu’à partir de chacune d’elles, on retrouve son développement dans la suivante et sa répartition dans la Moyenne région du Fleuve Rouge où se trouvent les provinces de Phú Thọ, Hà Nội, Vĩnh Phúc, Bắc Ninh, Ninh Bình etc…On peut dire que c’est le territoire originel sacré du peuple vietnamien.

Selon le professeur d’archéologie Hà Văn Tấn, ces cultures peuvent se distinguer facilement grâce à leur céramique. Pour connaître l’origine du peuple vietnamien, il faut remonter à la culture Phùng Nguyên il y a environ 4000 ans. C’est à l’époque où notre pays Văn Lang était gouverné par les rois Hùng dans les légendes. Selon l’observation du professeur d’archéologie Hà văn Tấn, les tribus de la culture Phùng Nguyên constituent le premier noyau dans le processus de formation du groupe ethnique Việt-Mường et celui de construction de la nation. Au début, les artefacts de Phùng Nguyên trouvés dans les fouilles ont atteint un niveau très sophistiqué: le jade, la pierre, la céramique, l’os, la corne que tout le monde a identifiés comme appartenant à la fin du Néolithique, notamment dans les techniques de fabrication de la pierre et de la céramique. Mais en présence d’un certain nombre d’objets en bronze trouvés plus tard, les chercheurs tels que Hà Văn Tấn, Trần Quốc Vượng étaient d’accord de reconnaître que la culture de Phùng Nguyên était à l’origine de l’âge du bronze au nord du Vietnam et qu’elle avait une influence notable plus tard dans de nombreuses régions de l’Asie du Sud-Est par l’intermédiaire de la culture Đồng Sơn.

Les habitants de la culture Phùng Nguyên sont-ils les Luo Yue, les ancêtres des Vietnamiens d’aujourd’hui (les Kinh), ou sont-ils simplement un groupe ethnique Yue ou bien les gens venus de quelque part pour s’installer dans la région du Fleuve Rouge? Sont-ils venus de la Malaisie ou du fleuve Yangtsé ? L’origine du peuple vietnamien est très confuse dans l’histoire car en se fiant uniquement à des légendes, il nous est difficile de croire et d’accepter le caractère irrationnel dans la légende du « Lạc Long Quân-Âu Cơ » avec une poche faisant éclore une centaine d’œufs. Pour le chercheur Paul Pozner [1] l’historiographie vietnamienne se base sur une très longue et permanente tradition historique, laquelle est représentée par une tradition historique orale durant le 3ème – 1ère moitié du premier millénaire avant notre ère sous forme de légendes historiques dans les temples des cultes des ancêtres.

Les deux vers suivants:

Trăm năm bia đá thì mòn

Ngàn năm bia miệng vẫn còn trơ trơ.

Avec cent ans, la stèle de pierre continue à se détériorer

Avec mille ans, les paroles des gens continuent à rester en vigueur

témoignent de la pratique menée sciemment par les Vietnamiens dans la préservation de la culture dont ils ont hérité durant la période de Hồng Bàng face à la répression incessante de la Chine au moment de l’annexion de leur pays.

De la confiscation de nombreux tambours en bronze par le généralissime Ma Yuan de la dynastie des Han de l’Est pour les faire fondre en chevaux offerts à son empereur jusqu’à la destruction systématique des pagodes, l’autodafé des livres, l’arrêt et la condamnation à l’exil plus de 10 000 vietnamiens talentueux dont Nguyễn An (ou Ruan An), l’architecte en chef de la Cité Interdite à Pékin sous le règne de Yongle (dynastie des Ming), cela nous a montré que les Chinois tentaient d’assimiler d’une manière méthodique et malveillante les Luo Yue, la seule ethnie dans les « Cent Yue » gardant encore l’indépendance jusqu’à ce jour. Heureusement, c’est seulement au cours des vingt dernières années depuis 1998 que les recherches sur la phylogénétique moléculaire effectuées par les groupes de recherche aux États-Unis et en Europe, avec notamment l’avancement des techniques d’analyse de l’ADN en anthropologie, nous facilitent d’obtenir les données sur l’ensemble des gènes et sur les molécules ADN de manière plus précise. Cela permet de n’avoir plus des accrocs historiques et de connaître plus clairement l’origine des Vietnamiens.

En quittant l’Afrique, les hommes préhistoriques avaient effectué la migration en deux vagues. La première vague s’orientait vers l’Asie du Sud-Est, y compris le Vietnam à travers la côte orientale de l’Inde vers 60 000-30 000 ans avant J.C. avant d’atteindre l’Australie et de remonter vers l’Amérique du Nord via le détroit de Béring et la deuxième vague tentait de remonter vers le Moyen-Orient et l’Asie centrale et de longer l’Himalaya jusqu’en Asie du Sud-Est, y compris le Vietnam, vers 30 000 ans avant J.C. grâce à des données génétiques connues. En se basant sur les documents des travaux de recherche génétique, un certain nombre d’auteurs vietnamiens (Cung Đình Thanh, Hà Văn Thùy, Lang Linh ou Hoàng Nguyễn) ont suggéré une théorie tout à fait compatible avec les légendes, l’histoire et les fouilles archéologiques entamées dans le passé au Vietnam.

C’est à l’époque en Asie du Sud-Est que les hommes préhistoriques (groupe Indonésien) issus de la fusion des deux races importantes mongoloïde et Australoïde, avaient laissé leur empreinte dans le bassin du Fleuve Rouge avec la célèbre culture Hoà Bình (18000-10000 B.C.) que l’archéologue française Madeleine Colani découvrit en 1922. C’est aussi la culture qui était à l’origine de la civilisation des Proto-Vietnamiens. Elle s’était répandue et avait influencé les cultures néolithiques de la Chine telles que les cultures Yangshao (Shanxi) et Hongshan. Le physicien britannique Stephen Oppenheimer est allé au-delà de ce que l’on pensa à cette l’époque en démontrant par des méthodes scientifiques et logiques que le berceau de la civilisation humaine se trouvait en Asie du Sud-Est dans « Paradis à l’Est ».

Selon les documents des travaux de la recherche génétique de McColl et de ses collègues [2], les habitants de Hoà Bình avaient à cette époque des gènes les plus proches de ceux du peuple Onge vivant sur l’île Andaman et n’étant pas encore fusionné avec d’autres groupes ethniques. C’est le type d’homme noir aux cheveux courts et bouclés que nous pouvons identifier avec les habitants de Hoà Bình. Ils étaient les premiers à bien connaître la culture du riz irrigué et d’autres techniques agricoles comme la culture des céréales etc… (La cave des esprits par exemple). Pourtant ils étaient décrits par les archéologues occidentaux comme des gens vivant de pêche, de chasse et de cueillette. Pire encore, dans les « Écrits des Han postérieurs (Hậu Hán Thư) », il est également dit que les gouverneurs chinois Si Kouang (Tich Quang) et Ren Yan (Nham Dien) aviaent appris à nos ancêtres à cultiver le riz. C’est absurde et parano.

Puis il y a une grande inondation (un déluge) qui a eu lieu il y a 12.000 ans. Cela a fait s’enfoncer dans la mer une grande partie des terres habitées par des populations préhistoriques comme le bassin du Fleuve Rouge. Ces dernières étaient obligées de le quitter et de s’enfuir en se réfugiant partout dans le monde: à l’est dans l’océan Pacifique, à l’ouest en Inde ou au nord dans la région du fleuve Yangtsé en emmenant avec elles les objets caractéristiques de la culture Hoa Binh trouvés dans le site Xian Ren Dong (Tiên Nhân động) de la province Jiangxi (Giang Tây) par exemple. D’après les travaux de recherche génétique, il s’agit bien d’anciens habitants de l’Asie du Sud-Est (ou les gens de Hoà Bình) faisant leur arrêt dans le bassin du fleuve Yangtze car cet endroit était propice à l’époque au développement de la riziculture irriguée. Mais il y a encore un autre groupe de personnes qui aimaient à continuer leur migration vers l’Asie de l’Est en emmenant leur riz domestiqué (site de Shangshan, Thượng Sơn) et leur millet et en empruntant le passage à Zhejiang (Chiết Giang) pour s’installer non seulement dans le delta du Fleuve Jaune mais aussi jusqu’à la région du Fleuve Liao dans la Mongolie intérieure de la Chine d’aujourd’hui (Liêu Hà, Nội Mông Trung Hoa).

C’est dans cette dernière qu’ils s’étaient unis aux autochtones nomades de l’Asie du Nord dont les vestiges étaient trouvés dans la grotte de la Porte du Diable sur le territoire russe limitrophe de la Corée (Sibérie occidentale) pour donner naissance à une race mongoloïde du Nord typique et une culture nommée « Hong Shan ( Hồng Sơn) » découverte de la régon de la Mongolie intérieure jusqu’à Liaoning. Ces Mongoloïdes du Nord étaient descendus dans la région du fleuve Jaune où vivaient les Hmongs qui étaient très doués en agriculture. Ils faisaient partie de la tribu Yi. Étant à l’origine le dessin d’un homme 人 portant un arc 弓, ce caractère « Yi » 夷 nous donne une idée précise sur la particularité de ces gens du Nord. Ils se distinguaient par le tir à l’arc et ils étaient très habiles au combat. C’est pourquoi ils réussirent à gagner les victoires contre les Hmong dirigés par leur leader Chiyou (Xi Vưu) à Zhuolu (Trác Lộc) en l’an 2704 B.C. dans la province Hebei (Hà Bắc) et Shennong (Thần Nông) trois fois de suite, ce qui donna naissance ensuite à la civilisation chinoise (Yangshao (Ngưỡng Thiều) et Dawenkou (Đại Vấn Khẩu) et à la nouvelle race mongoloïde du Sud avec les anciens habitants de l’Asie du Sud Est. Étant de plus en plus nombreux, ces nouveaux mongoloïdes du Sud devenaient ainsi les sujets du bassin du fleuve Jaune et les ancêtres des Chinois d’aujourd’hui.

En revanche, il y a aussi les Pré-Austronésiens -Tai-Kadai d’origine de l’Asie du Sud-Est qui avaient migré et s’étaient installés plus tard dans la région de Shandong. Puis à partir de celle-ci, ils étaient descendus dans le bassin du fleuve Yangtsé (ou fleuve Bleu, Dương Tử) il y a environ 6000 ans en emmenant avec eux le millet. Cette céréale a été trouvée sur le site de Tanshishan datant de 3500 ans avant J.C. environ dans la région du Fujian [3] selon les données des travaux de la recherche génétique [4][5].Les Austronésiens continuaient à migrer vers l’île de Taïwan et s’étaient dispersés ensuite dans les îles de l’Asie du Sud-Est.

Dans le bassin du fleuve Yangtsé, la formation de la communauté ethnique Yue-Tai-Kadai avait lieu du fait de la proximité des habitants autochtones de la famille linguistique austroasiatique et des Pré-Austronésiens -Tai-Kadai venus plus tard. Compte-tenu des facteurs génétiques dus à la fusion des autochtones et des nouveaux venus issus des vagues de migration de l’Asie du Nord vers l’Asie du Sud et vice versa sur des milliers d’années, il y a eu des modifications dans la structure des gènes, notamment sous l’influence de l’environnement, cela a provoqué une changement naturel de la taille et de la couleur de la peau et a conduit à la formation des Mongoloïdes du Nord et du Sud et des Yue de la famille austro-asiatique. Celle-ci est constituée de plusieurs ethnies dans l’Asie de l’Est. Même dans leur langue on constate qu’il y a l’emprunt provenant de la coexistence des groupes ethniques Yue dans la région du fleuve Yangtsé. C’est pour cela qu’il y a l’apparition de la famille linguistique austroasiatique. Les linguistes américains Mei Tsulin et Norman Jerry [6] ont identifié 15 mots empruntés de la langue austroasiatique dans les textes chinois sous la dynastie des Han. C’est le cas typique des caractères chinois comme le mot jiang 囝 (ou la rivière en vietnamien) ou le mot nu 弩 (ou ná en vietnamien). Ils sont amenés à conclure qu’il y a un contact entre les deux langues chinoise et austroasiatique dans la partie sud de la Chine actuelle. C’est ici que les Yue se rendaient compte qu’ils sont clairement différents des tribus nomades de la région du fleuve Jaune. Ils se disaient Yue.

Le mot « Yue (hache) » qu’ils utilisaient pour se désigner eux-mêmes en tant que les gens vivant dans la région du fleuve Yangtsé ou ayant l’habitude d’utiliser la hache pour cultiver les céréales et se défendre lorsqu’il y avait l’invasion des gens du Nord (les Chinois). Ceux-ci les considéraient toujours comme des Man Di (des Sauvages). Pourtant ce sont eux qui ont conduit à la formation des grandes civilisations comme Liangzhu et Shijahe. C’est grâce aux fouilles archéologiques entamées dans le cours inférieur du fleuve Yangtsé dans les années 1970 que l’on connaît la culture de Liangzhu. Celle-ci était bien plus avancée que la culture de Yang Shao puisqu’elle remonta à 3300 ans avant J.C. avec la découverte des pictogrammes sculptés sur la pierre, les plastrons de tortue, les os des animaux dans les séances de divination et des offices religieux. Ces dessins figuratifs étaient antérieurs de plus de 2 000 ans aux inscriptions oraculaires des Shang. On sait que les habitants de Liangzhu avaient un mode de vie sédentaire stable avec un système d’irrigation avec de l’eau emmagasinée par des canaux et une organisation sociale nécessitant beaucoup de main-d’œuvre pour la production et la distribution.

Sont-ils les Man Di (sauvages) ou non ? Mais la prise de conscience nationale du peuple Yue est évidente et se retrouve très tôt sur un artefact de la culture de Liangzhu vers 3300 av. J.C., portant l’inscription suivante composée de 4 symboles que le chercheur chinois Đổng Sở Bình a réussi à décoder pour donner la signification suivante: la fédération des communautés Yue (Phương Việt hội thi).

C’est pour cela que les Chinois ont accepté la manière de s’identifier chez les Yue pour en parler dans les inscriptions oraculaires de la dynastie Shang et ont utilisé également des haches cérémonielles yue dans les sacrifices d’humains ou d’animaux selon la remarque de l’archéologue française Corinne Debaine-Fracfort. Étant considérée comme la culture de jade, la culture de Liangzhu avait de nombreux artefacts en jade tels que les haches en jade, les cylindres rituels cong, les disques bi rituels de jade en l’honneur du Ciel, les jades etc. Le tout a été découvert dans les tombes de la classe dirigeante et aristocratique tandis que la céramique a été réservée pour la classe inférieure. La hache cérémonielle en jade était à la fois une arme de cérémonie et un objet de pouvoir qui commença à être découvert à peine dans la culture de Liangzhu à Taihu (Jiangsu) dans l’aire du pays Xích Quỷ du roi Kinh Dương Vương, le premier ancêtre du clan Yue et père de Lạc Long Quân dans la légende. Selon l’écrivain vietnamien Nguyên Nguyên [7], le nom Kinh Dương Vương 涇陽王 peut se traduire en vietnamien: le roi Yue est solennel.

La légende selon laquelle Kinh Dương Vương monta sur le trône et fonda le royaume de Xích Quỷ en 2879 av. J.-C. après la formation de l’État de Liangzhu en 3300 av. J.C., montre que la naissance du royaume de Xích Quỷ correspond bien à la période foisonnante de la culture de Liangzhu. Le propriétaire de cette culture choisit pour son totem l’union d’un oiseau et d’un animal. Il y a ainsi une liaison étroite avec la dynastie des Hồng Bàng évoquant implicitement l’oiseau et le serpent càd la Fée et le Dragon.

En raison de l’élévation du niveau de la mer, les Yue ont dû se déplacer vers le cours moyen du fleuve YangTsé dans la région autour du lac Dongting (Động Đình Hồ). C’est ici qu’on voit la continuité par la naissance de la culture de Shijahe (Thạch Gia Hà) 2600-2000 ans av. J.C. Il s’agit d’une culture à la fin de l’âge de pierre polie à Hubei avec 1000 artefacts trouvés. Semblable à la ville de Liangzhu, la ville de Shijiahe possède un système de canaux creusés autour des zones urbaines et reliés aux rivières voisines. Parmi les artefacts trouvés, il y a un objet retenant l’attention de tout le monde. C’est un vase en céramique avec l’image d’un leader dont la tête est ornée d’une coiffure décorée de plumes d’oiseaux et qui convient parfaitement à la figure dansante portant un costume de plumes sur les tambours en bronze de la culture Dong Son (Ngọc Lũ par exemple). C’est le symbole du peuple Yue. La ville Shijahe est située sur le territoire du royaume Văn Lang. Compte-tenu de la description géographique dans la légende, on sait que ce dernier possède un territoire très vaste bordant au nord le lac Dongting (Động Đình hồ), au sud le Champa (Hồ Tôn) (Chiêm Thành), à l’est la mer de Hai Nan et à l’ouest le royaume Ba Thục (Sichuan), où de nombreuses tribus Yue vivent dispersées du cours moyen jusqu’au cours inférieur du fleuve Yangtse.

Le nom Văn Lang est dérivé de l’ancien mot Yue Blang ou Klang que les montagnards utilisent souvent pour désigner le totem, c’est peut-être un oiseau aquatique de la famille des hérons. Le royaume de Văn Lang peut être considéré à cette époque comme une fédération de communautés ethniques Yue. C’est aussi le premier état de l’ethnie Yue selon la légende de l’histoire vietnamienne. Il y a une chose à laquelle on doit prêter attention c’est que dans cette culture de Shijahe il y a un artefact appelé « Nha Chương » signifiant une dent de jade utilisée pour les cérémonies rituelles en l’honneur des montagnes et des fleuves. Cette lame de cérémonie a été découverte très tôt dans le site d’Erlitou (Nhị Lý Đầu) appartenant à la culture des Shang reconnue aujourd’hui par les archéologues. Mais dans la légende vietnamienne, on se réfère aussi à la confrontation militaire avec les Shang à travers l’histoire mythique du roi céleste Phù Đổng ou Saint Gióng). Donc il y a le contact entre le royaume de V ăn Lang et la culture des Yin-Shang. Cela montre enfin la vérité fondamentale de la légende, notamment avec un nombre assez important des « Nha Chương » découverts dans les anciens villages Phùng Nguyên et Xóm Rền considérés comme des sites appartenant à la culture de Phùng Nguyên.

En l’an 2000 avant J.C., il y avait une sécheresse dans la région du cours moyen du fleuve Yangtsé d’après les études archéologiques et météorologiques. Cela a obligé les habitants de Shijiahe et Liangzhu de migrer car ils ne pouvaient plus continuer les activités agricoles. En s’appuyant sur les travaux de recherche génétique de Hugh McColl et de ses collègues, on sait que la population agraire austro-asiatique a migré vers l’Asie du Sud Est il y a 2000 ans av. J.C. et a fusionné avec la population autochtone vivant de cueillette et de chasse dans une proportion négligeable. La fédération des tribus Yue du fleuve Yangtsé a été dissoute également. Cela a causé aussi la disparition de deux cultures de Liangzhu et Shijiahe. On constate que cette désintégration est très cohérente avec la légende de Lạc Long Quân Âu Cơ au moment de la séparation: 50 enfants ont suivi leur père pour aller à la plaine (Lạc Việt) tandis les 50 autres enfants ont accompagné leur mère Âu Cơ pour s’installer à la montagne (Âu Viet). Sous la gouvernance des rois Hùng, le royaume de Văn Lang se rétrécit aussi en l’an 1879 avant J.C. avec les 15 tribus.

Dans le delta du fleuve Jaune, on compte trois dynasties successives : Xia (2000-1600 avant J.C.), Yin-Shang (1600-1050 avant J.C.) et Zhou (1050-221 avant J.C) marquant enfin la fin de la préhistoire et les débuts de la civilisation chinoise. Dans le bassin du fleuve Yangtsé, de nombreux petits états Yue se sont formés dans un premier temps, puis ils se sont progressivement annexés pour donner naissance à des états importants que nous connaissons à travers l’histoire chinoise comme l’état Wu-Yue de Wu Zixu (Ngũ Tử Tư) ou l’état Yue de Goujian (Câu Tiễn) durant les périodes des Printemps et Automnes et la période des Royaumes combattants (770-221 avant J.C.). Puis ces derniers étaient annexés à leur tour par Ngô Khởi (Wu Qi) de l’état Chu avant l’unification de la Chine par Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng).

En résumé, les habitants agriculteurs Yue qui étaient de retour à cette époque en Asie du Sud-Est et dans le delta du fleuve Rouge sont les descendants des peuples préhistoriques d’Asie du Sud-Est (ou les gens de la culture Hoà Bình) ayant migré vers la région du fleuve Yangtsé il y a 12 000 ans.

Ce sont les ancêtres des Vietnamiens d’aujourd’hui. C’est grâce aux caractéristiques anthropologiques et génétiques, aux coutumes et à la langue que nous avons le droit d’affirmer que nous sommes désormais les Mongoloïdes du Sud appartenant à la famille des langues austroasiatiques malgré qu’il reste seulement en nous des légendes pour prouver notre origine après 1000 ans de domination chinoise.

English version

Phùng Nguyên culture

Tìm về cội nguồn của dân tộc Việt.

Phùng Nguyên is the name of a village with the same name in the Lâm Thao district of Phú Thọ province where the remains of this culture are found. It is now known that the Đồng Sơn culture is the culture of the Lo Yue, who are the ancestors of today’s Vietnamese. Thanks to archaeological excavations carried out in important places with multiple cultural layers, Vietnamese archaeologists have discovered that there is no gap separating them, as is the case with the Đình Chàng site in Đồng Anh commune (Hanoi). It is within the Gò Mun site that the burial tombs of the Đồng Sơn culture are found, but beneath the Đồng Sơn layer, there are the Đồng Đậu and Phùng Nguyên cultures. This shows that there is no break in continuity between these cultures. Thanks to this, we can see the Phùng Nguyên-Đồng Đậu-Gò Mun-Đồng Sơn genealogy that archaeologists have established very precisely with the confirmation of multiple radiocarbon datings. These cultures succeed each other over time. This means that from each of them, their development is found in the next and their distribution in the Middle Red River region where the provinces of Phú Thọ, Hà Nội, Vĩnh Phúc, Bắc Ninh, Ninh Bình, etc. are located. It can be said that this is the sacred original territory of the Vietnamese people.

According to archaeology professor Hà Văn Tấn, these cultures can be easily distinguished by their ceramics. To understand the origin of the Vietnamese people, one must go back to the Phùng Nguyên culture about 4000 years ago. This was the time when our country Văn Lang was ruled by the Hùng kings in legends. According to the observation of archaeology professor Hà Văn Tấn, the tribes of the Phùng Nguyên culture constitute the first core in the process of forming the Việt-Mường ethnic group and the construction of the nation. Initially, the Phùng Nguyên artifacts found in excavations reached a very sophisticated level: jade, stone, ceramics, bone, horn, all identified as belonging to the late Neolithic period, especially in the techniques of stone and ceramic making. But with the presence of a number of bronze objects found later, researchers such as Hà Văn Tấn and Trần Quốc Vượng agreed to recognize that the Phùng Nguyên culture was the origin of the Bronze Age in northern Vietnam and had a notable influence later in many regions of Southeast Asia through the Đông Sơn culture.

Are the inhabitants of the Phùng Nguyên culture, the Luo Yue, the ancestors of today’s Vietnamese (the Kinh), or are they simply a Yue ethnic group or people who came from somewhere else to settle in the Red River region? Did they come from Malaysia or the Yangtze River? The origin of the Vietnamese people is very confusing in history because, relying solely on legends, it is difficult for us to believe and accept the irrational nature in the legend of « Lạc Long Quân-Âu Cơ » with a pouch hatching a hundred eggs. For researcher Paul Pozner [1], Vietnamese historiography is based on a very long and continuous historical tradition, which is represented by an oral historical tradition during the 3rd to the first half of the first millennium BCE in the form of historical legends in the temples of ancestor worship.

The following two verses

Trăm năm bia đá thì mòn

Ngàn năm bia miệng vẫn còn trơ trơ.

With a hundred years, the stone stele continues to deteriorate

With a thousand years, the words of the people continue to remain in force

testify to the practice knowingly carried out by the Vietnamese in preserving the culture they inherited during the Hồng Bàng period in the face of incessant repression from China at the time of the annexation of their country.

From the confiscation of numerous bronze drums by the generalissimo Ma Yuan of the Eastern Han dynasty to melt them into horses offered to his emperor, to the systematic destruction of pagodas, the burning of books, the arrest and exile of more than 10,000 talented Vietnamese including Nguyễn An (or Ruan An), the chief architect of the Forbidden City in Beijing under the reign of Yongle (Ming dynasty), this has shown us that the Chinese attempted to assimilate the Luo Yue in a methodical and malicious manner, the only ethnic group among the « Hundred Yue » still maintaining independence to this day. Fortunately, it is only in the last twenty years since 1998 that research on molecular phylogenetics conducted by research groups in the United States and Europe, notably with advances in DNA analysis techniques in anthropology, has made it easier for us to obtain data on the entire genome and DNA molecules more precisely. This allows us to overcome historical gaps and to understand more clearly the origin of the Vietnamese.

When leaving Africa, prehistoric humans migrated in two waves. The first wave headed towards Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, via the eastern coast of India around 60,000-30,000 years B.C., before reaching Australia and moving up to North America via the Bering Strait. The second wave attempted to move up towards the Middle East and Central Asia and to follow the Himalayas to Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, around 30,000 years B.C., according to known genetic data. Based on genetic research documents, a number of Vietnamese authors (Cung Đình Thanh, Hà Văn Thùy, Lang Linh, or Hoàng Nguyễn) have suggested a theory fully compatible with legends, history, and archaeological excavations carried out in the past in Vietnam.

It was during this time in Southeast Asia that prehistoric humans (the Indonesian group), resulting from the fusion of the two major races Mongoloid and Australoid, left their mark in the Red River basin with the famous Hoà Bình culture (18,000-10,000 B.C.), which the French archaeologist Madeleine Colani discovered in 1922. This culture was also the origin of the Proto-Vietnamese civilization. It spread and influenced the Neolithic cultures of China, such as the Yangshao (Shanxi) and Hongshan cultures. The British physicist Stephen Oppenheimer went beyond what was thought at the time by demonstrating through scientific and logical methods that the cradle of human civilization was located in Southeast Asia in the « Paradise in the East. »

According to the documents from the genetic research work of McColl and his colleagues [2], the inhabitants of Hoà Bình at that time had genes closest to those of the Onge people living on the Andaman Island and who had not yet merged with other ethnic groups. This is the type of black man with short, curly hair that we can identify with the inhabitants of Hoà Bình. They were the first to have a good knowledge of irrigated rice culture and other agricultural techniques such as cereal cultivation, etc. (The cave of spirits, for example). Yet they were described by Western archaeologists as people living by fishing, hunting, and gathering. Worse still, in the « Later Han Writings (Hậu Hán Thư), » it is also said that the Chinese governors Si Kouang (Tich Quang) and Ren Yan (Nham Dien) taught our ancestors to cultivate rice. This is absurd and paranoid.

Then there was a great flood (a deluge) that took place 12,000 years ago. This caused a large part of the lands inhabited by prehistoric populations, such as the Red River basin, to sink into the sea. These populations were forced to leave and flee, seeking refuge all over the world: to the east in the Pacific Ocean, to the west in India, or to the north in the Yangtze River region, taking with them the characteristic objects of the Hoa Binh culture found at the Xian Ren Dong site (Tiên Nhân cave) in Jiangxi province, for example. According to genetic research, these were indeed ancient inhabitants of Southeast Asia (or the Hoa Binh people) who stopped in the Yangtze River basin because this place was favorable at the time for the development of irrigated rice cultivation. But there was also another group of people who liked to continue their migration towards East Asia, bringing their domesticated rice (Shangshan site, Thượng Sơn) and millet, and using the passage through Zhejiang to settle not only in the Yellow River delta but also as far as the Liao River region in Inner Mongolia of present-day China.

It is in this latter group that they had united with the nomadic indigenous peoples of Northern Asia, whose remains were found in the Devil’s Gate Cave on Russian territory bordering Korea (Western Siberia), giving rise to a typical Northern Mongoloid race and a culture named « Hong Shan (Hồng Sơn) » discovered from the Inner Mongolia region to Liaoning. These Northern Mongoloids descended into the Yellow River region where the Hmong lived, who were very skilled in agriculture. They were part of the Yi tribe. Originally, the character for a man 人 carrying a bow 弓, this character « Yi » 夷 gives us a precise idea about the particularity of these Northern people. They were distinguished by archery and were very skilled in combat. That is why they succeeded in winning victories against the Hmong led by their leader Chiyou (Xi Vưu) at Zhuolu (Trác Lộc) in 2704 B.C. in Hebei province (Hà Bắc) and Shennong (Thần Nông) three times in a row, which subsequently gave birth to Chinese civilization (Yangshao (Ngưỡng Thiều) and Dawenkou (Đại Vấn Khẩu)) and to the new Southern Mongoloid race together with the ancient inhabitants of Southeast Asia. Increasing in number, these new Southern Mongoloids thus became the subjects of the Yellow River basin and the ancestors of the Chinese of today.

On the other hand, there are also the Pre-Austronesians – Tai-Kadai of Southeast Asian origin who had migrated and later settled in the Shandong region. From there, they moved down into the Yangtze River basin (or Blue River, Dương Tử) about 6000 years ago, bringing millet with them. This cereal was found at the Tanshishan site dating to around 3500 BC in the Fujian region [3], according to genetic research data [4][5]. The Austronesians continued to migrate to the island of Taiwan and then dispersed into the islands of Southeast Asia.

In the Yangtze River basin, the formation of the Yue-Tai-Kadai ethnic community took place due to the proximity of the indigenous inhabitants of the Austroasiatic language family and the later-arriving Pre-Austronesian Tai-Kadai peoples. Considering the genetic factors resulting from the fusion of the indigenous people and the newcomers from waves of migration from North Asia to South Asia and vice versa over thousands of years, there have been changes in the gene structure, notably influenced by the environment. This caused a natural change in size and skin color and led to the formation of the Northern and Southern Mongoloids and the Yue of the Austroasiatic family. This family consists of several ethnic groups in East Asia. Even in their language, one can observe borrowings resulting from the coexistence of the Yue ethnic groups in the Yangtze River region. This is why the Austroasiatic language family emerged. American linguists Mei Tsulin and Norman Jerry [6] identified 15 loanwords from the Austroasiatic language in Chinese texts under the Han dynasty. This is typically the case with Chinese characters such as the word jiang 囝 (or river in Vietnamese) or the word nu 弩 (or ná in Vietnamese). They are led to conclude that there was contact between the Chinese and Austroasiatic languages in the southern part of present-day China. It is here that the Yue realized they were clearly different from the nomadic tribes of the Yellow River region. They called themselves Yue.

The word « Yue (axe) » that they used to refer to themselves as the people living in the Yangtze River region or who were accustomed to using the axe to cultivate cereals and defend themselves during invasions by people from the North (the Chinese). These were always considered by them as Man Di (Savages). Yet it was they who led to the formation of great civilizations such as Liangzhu and Shijahe. It is thanks to the archaeological excavations begun in the lower course of the Yangtze River in the 1970s that the Liangzhu culture is known. This culture was much more advanced than the Yangshao culture since it dates back to 3300 BC with the discovery of pictograms carved on stone, turtle plastrons, animal bones used in divination sessions and religious ceremonies. These figurative drawings were more than 2,000 years earlier than the oracle inscriptions of the Shang. It is known that the inhabitants of Liangzhu had a stable sedentary lifestyle with an irrigation system storing water through canals and a social organization requiring a lot of labor for production and distribution.

Are they the Man Di (savages) or not? But the national consciousness of the Yue people is evident and can be found very early on an artifact from the Liangzhu culture around 3300 BC, bearing the following inscription composed of 4 symbols that the Chinese researcher Đổng Sở Bình managed to decode to give the following meaning: the federation of the Yue communities (Phương Việt hội thi).

That is why the Chinese accepted the way of identification among the Yue to speak about it in the oracle bone inscriptions of the Shang dynasty and also used Yue ceremonial axes in human or animal sacrifices, according to the observation of the French archaeologist Corinne Debaine-Fracfort. Considered as the jade culture, the Liangzhu culture had many jade artifacts such as jade axes, ritual cong cylinders, ritual bi jade discs in honor of Heaven, jades, etc. All were discovered in the tombs of the ruling and aristocratic class, while ceramics were reserved for the lower class. The ceremonial jade axe was both a ceremonial weapon and an object of power that began to be discovered only in the Liangzhu culture at Taihu (Jiangsu) in the area of the Xích Quỷ country of Kinh Dương Vương, the first ancestor of the Yue clan and father of Lạc Long Quân in legend. According to the Vietnamese writer Nguyên Nguyên [7], the name Kinh Dương Vương 涇陽王 can be translated into Vietnamese as: the solemn king of Yue.

The legend according to which Kinh Dương Vương ascended the throne and founded the kingdom of Xích Quỷ in 2879 BC, after the formation of the Liangzhu State in 3300 BC, shows that the birth of the kingdom of Xích Quỷ corresponds well to the flourishing period of the Liangzhu culture. The owner of this culture chose for its totem the union of a bird and an animal. There is thus a close connection with the Hồng Bàng dynasty, implicitly evoking the bird and the serpent, i.e., the Fairy and the Dragon.

Due to the rising sea level, the Yue had to move to the middle course of the Yangtze River in the region around Dongting Lake (Động Đình Hồ). It is here that continuity is seen with the emergence of the Shijahe culture (Thạch Gia Hà) from 2600-2000 BCE. This is a culture from the late polished stone age in Hubei with 1000 artifacts found. Similar to the city of Liangzhu, the city of Shijiahe has a system of canals dug around urban areas and connected to nearby rivers. Among the artifacts found, there is an object that draws everyone’s attention. It is a ceramic vase with the image of a leader whose head is adorned with a headdress decorated with bird feathers and which perfectly matches the dancing figure wearing a feather costume on the bronze drums of the Dong Son culture (Ngọc Lũ for example). It is the symbol of the Yue people. The city of Shijahe is located in the territory of the Văn Lang kingdom. Considering the geographical description in the legend, it is known that the latter has a very vast territory bordering to the north Dongting Lake (Động Đình hồ), to the south Champa (Hồ Tôn) (Chiêm Thành), to the east the Hai Nan Sea, and to the west the Ba Thục kingdom (Sichuan), where many Yue tribes live scattered from the middle course to the lower course of the Yangtze River.

The name Văn Lang is derived from the ancient word Yue Blang or Klang that the mountaineers often use to designate the totem; it may be a water bird from the heron family. The kingdom of Văn Lang can be considered at that time as a federation of Yue ethnic communities. It is also the first state of the Yue ethnicity according to the legend of Vietnamese history. One thing to pay attention to is that in this Shijahe culture there is an artifact called « Nha Chương, » meaning a jade tooth used for ritual ceremonies honoring the mountains and rivers. This ceremonial blade was discovered very early at the Erlitou site (Nhị Lý Đầu), belonging to the Shang culture recognized today by archaeologists. But in Vietnamese legend, there is also a reference to the military confrontation with the Shang through the mythical story of the celestial king Phù Đổng or Saint Gióng. Thus, there was contact between the kingdom of Văn Lang and the Yin-Shang culture. This finally shows the fundamental truth of the legend, especially with a fairly significant number of « Nha Chương » discovered in the ancient Phùng Nguyên and Xóm Rền villages, considered sites belonging to the Phùng Nguyên culture.

In the year 2000 BC, there was a drought in the middle course region of the Yangtze River according to archaeological and meteorological studies. This forced the inhabitants of Shijiahe and Liangzhu to migrate because they could no longer continue agricultural activities. Based on the genetic research work of Hugh McColl and his colleagues, it is known that the Austroasiatic agrarian population migrated to Southeast Asia around 2000 BC and merged with the indigenous population living by gathering and hunting in a negligible proportion. The federation of the Yue tribes of the Yangtze River was also dissolved. This also caused the disappearance of the Liangzhu and Shijiahe cultures. It is noted that this disintegration is very consistent with the legend of Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ at the time of separation: 50 children followed their father to go to the plains (Lạc Việt) while the other 50 children accompanied their mother Âu Cơ to settle in the mountains (Âu Viet). Under the governance of the Hùng kings, the kingdom of Văn Lang also shrank in the year 1879 BC with the 15 tribes.

In the Yellow River delta, there are three successive dynasties: Xia (2000-1600 BC), Yin-Shang (1600-1050 BC), and Zhou (1050-221 BC), marking the end of prehistory and the beginnings of Chinese civilization. In the Yangtze River basin, many small Yue states initially formed, then gradually annexed each other to give rise to significant states known in Chinese history such as the Wu-Yue state of Wu Zixu (Ngũ Tử Tư) or the Yue state of Goujian (Câu Tiễn) during the Spring and Autumn periods and the Warring States period (770-221 BC). These were then annexed in turn by Ngô Khởi (Wu Qi) of the Chu state before the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng).

In summary, the Yue farming inhabitants who were present at that time in Southeast Asia and in the Red River delta are the descendants of prehistoric peoples of Southeast Asia (or the people of the Hoà Bình culture) who migrated to the Yangtze River region 12,000 years ago.

They are the ancestors of today’s Vietnamese. It is thanks to anthropological and genetic characteristics, customs, and language that we have the right to affirm that we are now the Southern Mongoloids belonging to the Austroasiatic language family, even though only legends remain within us to prove our origin after 1000 years of Chinese domination.

[Return CIVILISATION]

Tài liều tham khảo

Stephen Oppenheimer: Địa đàng ở Phương Đông. Nhà Xuất Bản Lao Động.2005

Hà văn Tấn: Theo dấu các văn hóa cổ. Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội. Hànội 1998.

Corinne Debaine-Francfort : La redécouverte de la Chine ancienne. Editions Gallimard 1998.

Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1.

Bình Nguyên Lộc: Lột trần Việt ngữ. Talawas

[1] Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

[2]. Hugh McColl, Fernando Racimo, Lasse Vinner, et al. (2018). The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia. Science; 361(6397):88-92.

[3] Zuo, Xinxin & Jin, Jianhui & Huang, Yunming & wei, Ge & jinqi, Dai & wei, Wu & fusheng, Li & taoqin, Xia & xipeng, Cai (2021). Earliest arrival of millet in the South China coast dating back to 5,500 years ago. Journal of Archaeological Science

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440321000261

[4] Sun, Jin & Li, Yingxiang & Ma, Pengcheng & Yan, Shi & Cheng, Hui-Zhen & Fan, Zhi-Quan & Deng, Xiao-Hua & Ru, Kai & Wang, Chuan-Chao & Chen, Gang & Wei, Ryan. (2021). Shared paternal ancestry of Han, Tai-Kadai-speaking, and Austronesian-speaking populations as revealed by the high resolution phylogeny of O1a-M119 and distribution of its sub-lineages within China. American journal of physical anthropology. 174. 10.1002/ajpa.24240.

[5] Ko AM, Chen CY, Fu Q, et al. Early Austronesians: into and out of Taiwan. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(3):426-436. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003.

[6] Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin 1976 The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

[7]Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương.