Thách thức

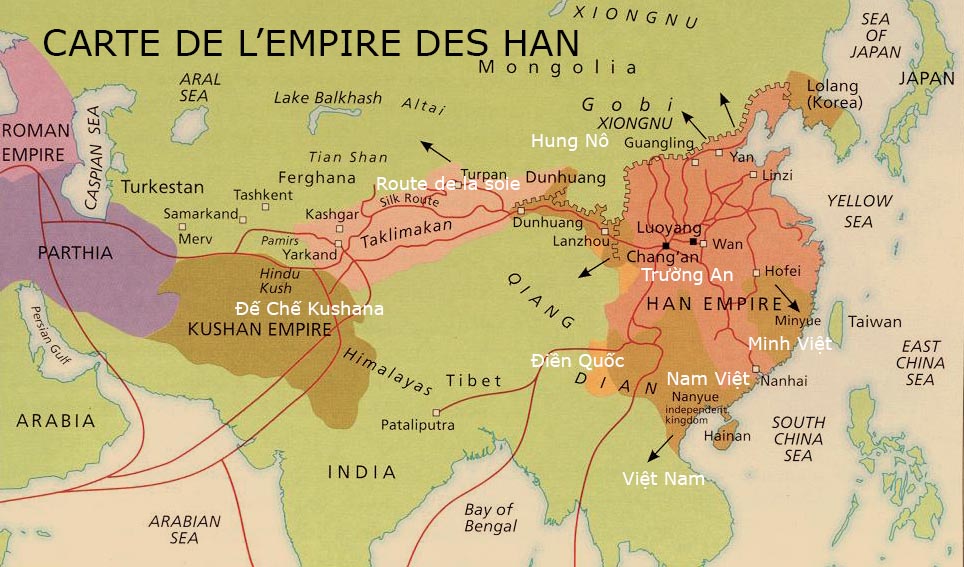

Từ nầy không xa lạ đối với người dân Việt. Mặt khác, nó còn đồng nghĩa với sự kiên trì, kháng cự, khéo léo và đối đầu dành cho những người mảnh khảnh nầy mà chân lúc nào cũng chôn vùi dưới bùn ở các ruộng lúa kể từ buổi ban sơ. Từ thế hệ này sang thế hệ khác, họ đã không ngừng chấp nhận mọi thách thức áp đặt bởi một thời tiết khắc nghiệt của một môi trường sống không bao giờ thuận lợi và một nước Trung Hoa mà họ vừa xem như là một người anh cả láng giềng mà cũng là kẻ thù truyền kiếp của họ. Đối với đế chế Trung Hoa nầy, họ lúc nào cũng có sự ngưỡng mộ đáng kinh ngạc nhưng đồng thời họ thể hiện sự kháng cự không thể tưởng tượng được vì lúc nào ở nơi họ cũng có sự quyết tâm để bảo vệ nền độc lập dân tộc và những đặc thù văn hóa mà họ đã có từ 4 nghìn năm. Đế chế Trung Hoa đã cố gắng hán hóa bao lần Việt Nam suốt thời kỳ Bắc thuộc có đến nghìn năm nhưng chỉ thành công làm mờ nhạt đi một phần nào các đặc điểm của họ mà thôi và nhận thấy mỗi lần có cơ hội thuận lợi, họ không ngớt bày tỏ sự kháng cự và sự khác biệt hoàn toàn. Họ còn tìm cách đương đầu với người Trung Hoa trên lãnh vực văn hóa mà được nhắc lại qua những câu chuyện còn được kể lại cho đến ngày nay trong lịch sử văn học Việt Nam. Theo dao ngôn được truyền tụng trong dân gian, sau khi thành công chế ngự được cuộc khởi nghĩa của hai Bà Trưng (Trưng Trắc Trưng Nhị) và chinh phục xứ Giao Chỉ (quê hương của người dân Việt), Phục Ba tướng quân Mã Viện của nhà Đông Hán truyền lệnh dựng cột đồng cao nhiều thước ở biên thùy Trung-Việt vào năm 43 và có được ghi chép trên cái bảng treo như sau:

Ðồng trụ triệt, Giao Chỉ diệt

Ðồng trụ ngã, Giao Chỉ bị diệt.

Để tránh sư sụp đổ của đồng trụ, người dân Việt cùng nhau vun đấp bằng cách mỗi lần đi ngang qua mỗi người vứt bỏ đi một cục đất nho nhỏ khiến đồng trụ huyền thoại nầy biến mất dần dần theo ngày tháng để trở thành một gò đất. Cố tình trêu nghẹo và mĩa mai trên sự sợ hải và nổi kinh hoàng mất nước của người dân Việt, vua nhà Minh Sùng Trinh ngạo mạng đến nỗi không ngần ngại cho cận thần ra câu đối như sau với sứ thần Việt Nam Giang Văn Minh (1582-1639) trong buổi tiếp tân:

Đồng trụ chí kim đài dĩ lục

Cột đồng đến giờ đã xanh vì rêu.

để nhắc nhở lại sự nổi dậy của hai bà Trưng bị quân Tàu tiêu diệt.

Không lay chuyển trước thái độ lố bịch nầy, sứ thần Giang Văn Minh trả lời một cách thông suốt lạ thường nhất là với lòng quyết tâm cứng cỏi:

Ðằng giang tự cổ huyết do hồng

Sông Bạch Đằng từ xưa vẫn đỏ vì máu

để nhắc nhở lại với vua nhà Minh những chiến công hiển hách của người dân Việt trên sông Bạch Đằng.

Không phải lần đầu có cuộc thi văn học giữa hai nước Trung Hoa và Việt Nam. Ở thời đại của vua Lê Đại Hành (nhà Tiền Lê), nhà sư Lạc Thuận có cơ hội làm cho sứ giã nhà Tống Lý Gi ác tr ầm trồ ngư ỡng mộ bằng cách giã dạng làm người lái đò tiển đưa Lý Giác sang sông. Khi Lý Giác khám phá ra được hai con ngỗng đang đùa cợt trên đỉnh sóng và ngâm hai câu thơ đầu của bài tứ tuyệt như sau:

Ngỗng ngỗng hai con ngỗng

Ngữa mặt nhìn trời xanh

thì Lạc Thuận không ngần ngại đối lại qua hai câu thơ cuối như sau:

Nước biếc phô lông trắng

Chèo hồng sóng xanh khua

Trong bốn câu thơ nầy, người ta nhận thấy không những có sự ứng khẩu nhanh chóng của sư Lạc Thuận mà còn có cả sự tài tình của ông trong việc dàn dựng song song những thuật ngữ và ý kiến tương đồng trong bài tứ tuyệt nầy.

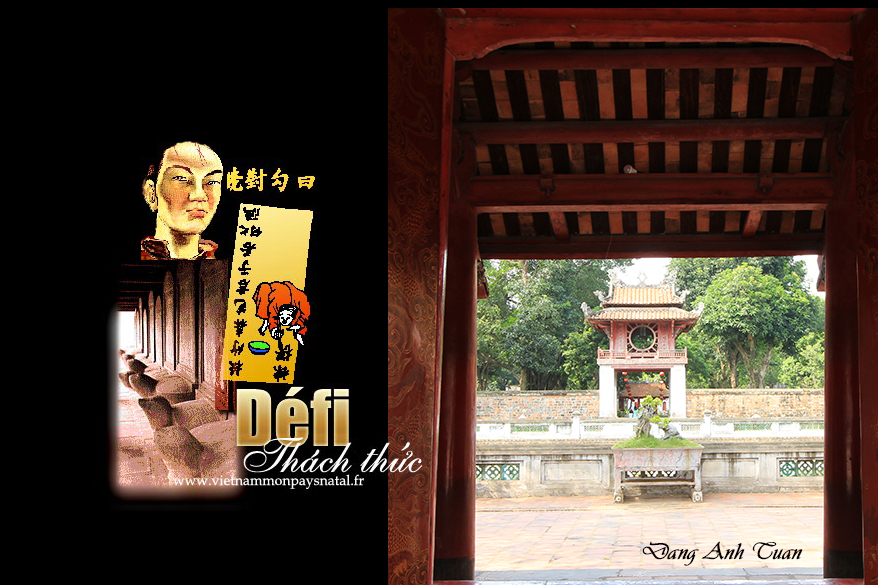

Hình ảnh nhà thờ Giang Văn Minh và văn miếu

Nhưng nói công lao trong việc đối đầu thì phải dành dĩ nhiên cho học giả Mạc Đĩnh Chi vì ông nầy trong thời gian ở Trung Quốc, đã thể thể hiện được khả năng chống cự mà còn có tài năng vô song để biết đối đáp lại một cách khéo léo tất cả mọi câu hỏi và tránh được mọi cạm bẫy. Ông được gửi đi sang Tàu vào năm 1314 bởi vua Trần Anh Tôn sau khi vua đánh bại quân Mông Cổ của Hốt Tất Liệt với tướng Trần Hưng Đạo. Do sự chậm trể vô tình, ông không có đến trình diện đúng giờ trước cổng thành ở biên giới Trung-Việt. Ông quan giữ cỗng thành chịu mở cửa nếu ông trả lời được một cách thích hợp câu hỏi mà người quan nầy đưa ra mà trong câu hỏi đó gồm có bốn chữ “quan”:

Quá quan trì, quan quan bế,

nguyện quá khách quá quan

Qua cửa quan chậm, cửa quan đóng,

mời khách qua đường qua cửa quan.

Không có chút nào nao núng cả trước sự thách thức văn học, ông trả lời ngay cho quan cổng với sự tự nhiên đáng kinh ngạc:

Xuất đối dị, đối đối nan, thỉnh tiên sinh tiên đối.

Ra câu đối dễ, đối câu đối khó

xin tiên sinh đối trước.

Trong lời đối đáp nầy, ông dùng chữ “đối” cũng 4 lần như chữ “quan” và nó được dựng lên ở vị trí của chữ “quan”. Mạc Đỉnh Chi còn điêu luyện biết giữ vần và những luật lệ âm điệu trong thơ để cho quan cổng biết là ông ở trong hoàn cảnh khó xữ với đoàn tùy tùng. Quan cổng rất hài lòng vô cùng. Ông nầy không ngần ngại mở cổng và đón tiếp Mạc Đỉnh Chi một cách linh đình. Chuyện nầy được báo cáo lên triều đình Bắc Kinh và làm nô nức biết bao nhiêu quan lại văn học Trung Hoa muốn đo tài cao thấp với ông trong lĩnh vực văn chương. Một ngày nọ, tại thủ đô Bắc Kinh, ông đang đi dạo với con lừa. Con nầy đi không đủ nhanh khiến làm một người Trung Hoa khó chịu đang theo sát ông trên đường. Quá cáu bởi sự chậm chạp này, quan lại nầy quay đầu nói lại với ông ta với một giọng kiêu ngạo và khinh bỉ:

Xúc ngã ky mã, đông di chi nhân dã, Tây di chi nhân dã?

Chạm ngựa ta đi là người rợ phương Ðông hay là người rợ phương Tây?

Ông quan lại lấy cảm hứng từ những gì ông đã học được trong cuốn sách Mạnh Tử để mô tả người những người man rợ không có cùng văn hóa với đế chế Trung Hoa bằng cách sử dụng hai từ » đông di « . Ngạc nhiên trước lời nhận xét tổn thương này khi ông biết rằng Trung Hoa bị cai trị vào thời điểm đó bởi các bộ lạc du mục (người Mông Cổ), Mạc Đỉnh Chi mới trả lời lại với sự hóm hỉnh đen tối của mình:

Át dư thừa lư, Nam Phương chi cường dư, Bắc phương chi cường dư

Ngăn lừa ta cưởi, hỏi người phương Nam mạnh hay người phương Bắc mạnh?

Một hôm, hoàng đế nhà Nguyên đã không ngần ngại ca ngợi sức mạnh của mình ví nó với mặt trời và làm cho Mạc Đỉnh Chi biết rằng Việt Nam chỉ được so sánh với mặt trăng, sẽ bị hủy diệt và thống trị sớm bởi người Mông Cổ. Điềm nhiên, Mạc Đỉnh Chi trả lời một cách kiên quyết và can đảm:

Nguyệt cung, kim đạn, hoàng hôn xa lạc kim

Trăng là cung, sao là đạn, chiều tối bắn rơi mặt trời.

Hoàng đế Kubilai Khan (Nguyễn Thê ‘Tổ) phải công nhận tài năng của ông và trao cho ông danh hiệu « Trạng Nguyên đầu tiên » (Lưỡng Quốc Trạng Nguyên) ở cả Trung Hoa và Việt Nam, khiến một số quan lại ganh tị. Một trong số người nầy cố tình làm bẽ mặt ông ta vào một buổi sáng đẹp trời bằng cách ví ông ta như một con chim bởi vì âm điệu đơn âm của ngôn ngữ, người dân Việt khi họ nói cho cảm giác người nghe như họ luôn luôn hót líu lo:

Quích tập chi đầu đàm Lỗ luận: tri tri vi tri chi, bất tri vi bất tri, thị tri

Chim đậu cành đọc sách Lỗ luận: biết thì báo là biết, chẳng biết thì báo chẳng biết, ấy là biết đó.

Đây là một cách để khuyên Mạc Ðỉnh Chi nên khiêm tốn hơn và cư xử như một người đàn ông có phẩm chất Nho giáo (Junzi). Mạc Đỉnh Chi trả lời bằng cách ví anh nầy như một con ếch. Người Trung Hoa thường có thói nói to và tóp tép lưỡi qua tư cách họ uống rượu.

Oa minh trì thượng đọc Châu Thư: lạc dữ đọc lạc nhạc, lạc dữ chúng lạc nhạc, thục lạc.

Châu chuộc trên ao đọc sách Châu Thu: cùng ít người vui nhạc, cùng nhiều người vui nhạc, đằng nào vui hơn.

Đó là một cách để nói lại với người quan lại nầy nên có một tâm trí lành mạnh để hành xử một cách công bằng và phân biệt nghiêm chỉnh.

Tuy rằng có sự đối đầu trong văn học, Mạc Đỉnh Chi rất nổi tiếng ở Trung Quốc. Ông được Hoàng đế của nhà Nguyên ủy nhiệm việc sáng tác bài văn tế để vinh danh sự qua đời của một công chúa Mông Cổ. Nhờ sự tôn trọng truyền thống của Trung Hoa dành cho những người tài năng Việt Nam, đặc biệt là các học giả có tài trí thông minh nhanh chóng và học hỏi mau lẹ mà Nguyễn Trãi đã được cứu bởi đại quản gia Hoàng Phúc. Trong tầm mắt của tướng Tàu Trương Phụ, Nguyễn Trãi là người phải giết, một người rất nguy hiễm cho chính sách bành trướng của Trung Hoa ở Việt Nam. Ông bị giam giữ bởi Trương Phụ trong thời gian ở Ðồng Quang (tên xưa của Hànội) trước khi ông theo Lê Lợi về sau ở Lam Sơn. Không có cử chỉ hào hiệp và bảo vệ của hoạn quan Hoàng Phúc, Lê Lợi không thể trục khỏi quân nhà Minh ra khỏi Việt Nam vì Nguyễn Trãi là cố vấn quan trọng và chiến lược gia nổi tiếng mà Lê Lợi cần dựa vào để lãnh đạo cuộc chiến tranh du kích trong thời gian mười năm đấu tranh chống lại Trung Quốc.

Cuộc đối đầu văn học này phai nhạt dần dần với sự xuất hiện của người Pháp tại Việt Nam và chấm dứt vĩnh viễn khi vua Khải Định quyết định chấm dứt hệ thống cuộc thi quan lại ở Việt Nam theo mô hình của người Trung Quốc dựa chủ yếu vào tứ thư Ngũ Kinh của Đức Khổng Tử.

Cuộc thi quan lại cuối cùng được tổ chức tại Huế vào năm 1918. Một hệ thống tuyển dụng kiểu Pháp khác đã được đề xuất trong thời kỳ thuộc địa. Do đó, Việt Nam không còn cơ hội để đối đầu văn học với Trung Quốc nửa và biểu hiện được sự khác biệt cũng như sự phản kháng trí tuệ và các đặc thù văn hóa.