Tại sao chọn gọi là Đất Rồng và Huyền Thoại ?

Version française

English version

Thư viện hình

Việt Nam là một quốc gia ở Đông Dương mà người dân rất yêu chuộng hoà bình, độc lập và tự do. Là người dân Việt thì phải có khả năng kháng cự lại trước hết việc đồng hóa hay là tư tưởng ngoại bang và hảnh diện có mang ở trong tĩnh mạch dòng máu của cha Rồng. Đối với người dân Việt, không còn sự hoài nghi nào cả vì qua truyền thuyết Con Rồng Cháu Tiên có từ thuở nào, họ là con cháu của cha Rồng mặc dầu họ biết rõ từ nay nguồn gốc qua các công trình khoa học di truyền. Họ là người thừa kế của nền văn hóa Hòa Bình và văn hóa Phùng Nguyên và thuộc về đại tộc Bách Việt, những bộ tộc sống rải rác ở phía nam sông Duơng Tử (Văn hóa Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà). Nuớc ở nơi nầy nó thấm nhuần với đất vì có thể là vậy nên quốc gia của họ thường được gọi là Đất Nước.

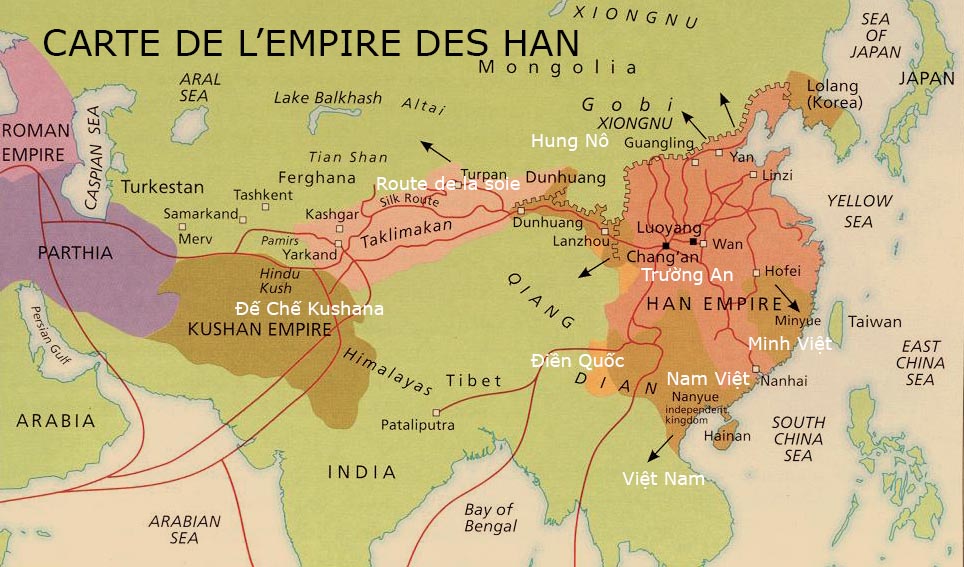

Cũng trên mãnh đất của đồng bằng sông Hồng nầy đã qua bao nhiêu thế kỷ trước Công Nguyên có một vương quốc sáng lâp một triều đại với các vua Hùng huyền thoại (nước Văn Lang). Sau đó được thay thế bởi nước Âu Việt của An Dương Vương (Thục Phán) mà thành trì Cổ Loa là thủ đô, một bằng chứng cụ thể của vương quốc nầy bị thôn tính về sau bởi Triệu Đà, một danh tướng của hoàng đế Trung Hoa Tần Thủy Hoàng. Ông nầy sáng lập ra nước Nam Việt (Nan Yue) lại bị thôn tính lúc đầu bởi Hán Vũ Đế và về sau bởi quân Tàu của danh tướng Mã Viện (Ma Yuan) dưới thời Hán Quang Vũ Đế (Guang wudi) với một nghìn năm bắc thuộc trước khi có cuộc chiến tranh giải phóng dân tộc của tuớng Ngô Quyền với chiến thắng rực rỡ trên vịnh Hạ Long, một trong di sản thế giới của Việt Nam.

Trong thời kỳ đô hộ, văn hóa Đồng Sơn bị hủy diệt. Người ta tìm thấy trong văn hóa nầy các thạp đồng và nhất là cái trống đồng uy nghiêm biểu hiệu quyền lực và đặc tính của dân tộc Việt đã bao lần suýt bị hủy diệt bởi đế chế Trung Hoa theo dòng lich sử. Đây không phải là lịch sử của các triều đại vua chúa (Đinh, Tiền Lê, Lý, Trần, Hậu Lê, Nguyễn vân vân…) hay các phong trào tư tưởng mà chính đây là lịch sử của dân tộc nông dân bền bỉ từ biên cương Việt Trung (Cao Bằng) đến mũi Cà Mau, vất vã khó nhọc để lại dấu ấn cho quang cảnh của mãnh đất nầy. Sự hy sinh của họ không phải là một từ vô ích. Các hào kiệt của họ thà làm qủi phương nam thay vì làm các vương công phương Bắc. Còn các nữ hào kiệt cũng không ngần ngại đáp lời sông núi. Đó là hai bà Trưng Trắc Trung Nhị, Dương Vân Nga, Triệu Ẩu, Ỷ Lan, Nguyễn Thị Giang (Cô Giang), Nguyễn thị Minh khai vân vân. Không người con Việt nào có thể quên câu nói bất diệt của Nguyễn Thái Học trước cái chết :

Chết vì Tổ Quốc.

Đây là số mệnh quá cao thượng, đáng khen

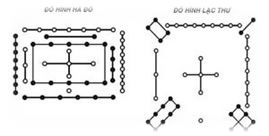

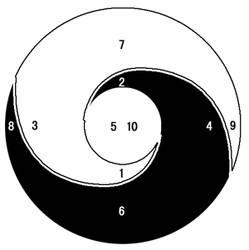

Trên chiến trường, không có lực luợng ngoại bang nào có thể đánh bại khi có chạm trán với người dân Việt. Chính họ dành được sự thắng lợi nhờ ba yếu tố nầy: Thiên Thời, Đia Lợi và Nhân Hòa. Chính yếu tố sau cùng nầy nó đem lại sự khác biệt trong cuộc chiến tranh tiêu hao. Nguyễn Trãi đã có dip nói rằng thà chinh phục nhân tâm hơn là chiếm đoạt thành trì. Hiên ngang trước quân giặc mạnh hơn họ thì họ cần phải kiên nhẫn nghĩ đến các thể thức thường được áp dụng trong lý thuyết Âm Dương : Lấy Yếu chống Mạnh hay Lấy Cụt chống Dài. Chính nhờ mưu lược nầy mà được Thống soái Trần Hưng Đạo sử dụng để chống lại hạm đội xâm lược Nguyên-Mông của Hốt Tất Liệt trong trận chiến sông Bạch Đằng năm 1288 và sau đó sĩ phu Nguyễn Trãi dành phần thắng lợi trong cuộc chống giặc nhà Minh của hoàng đế Vĩnh Lạc, người xây dựng Cố Cung ở Bắc Kinh được thiết kế bởi người Việt tên là Nguyễn An (Ruan An) và xua đuổi quân Tàu ra khỏi Việt Nam vào năm 1428.

Dùng chiến thuật di quân (Dương) trước sự bất động của quân nhà Thanh (Âm) phù hợp hoàn toàn với địa lợi, vua Quang Trung đánh bại chớp nhoáng quân địch vào năm 1788 trong 5 ngày Tết để lấy lại Thăng Long. Chính cũng Quang Trung lợi dụng sự không biết đia thế của quân địch mà dành phần thắng lợi thần tốc ở rạch Gầm-Xoài Mút (Mỹ Tho) với quân Xiêm La (Thái Lan) của tướng Chakri khi ông nầy gởi sang 50 vạn binh tiếp viện cho vua Gia Long. Không có dân tộc nào có thể cưởng lại trước sự bành trướng của người dân Việt trong cuộc Nam Tiến đến mũi Cà Mau. Đó là trường hợp của hai vương quốc Chămpa ở miền trung và Chân Lạp ở đồng bằng sông Cửu Long.

Dù bị nghìn năm bắc thuộc và có sự đóng góp văn hóa ngọai bang, những người nông dân con Việt mảnh khảnh nầy, chân vùi dưới bùn ở giữa các ruộng lúa, đã gìn giữ được những gì qúi giá nhất của các dân tộc trên thế giới. Đó là những truyền thống ( ca dao chẵng hạn) và tiếng Việt dựa trên chữ Hán sau nầy dùng chữ Latinh với ông thầy tu dòng tên là Alexandre de Rhodes. Chỉ còn bộ tộc Lạc Việt duy nhất thuộc đại tộc Bách Việt không bị hán hóa qua nhiều thế kỷ. Chính Đức Khổng Tử đã có từng so sánh sinh lực có ở nơi người Trung Hoa và người Lạc Việt, tổ tiên của người Việt Nam ngày nay: can đảm và vũ lực thuộc về người Trung Hoa, còn Lạc Việt thì khoan dung và nhân từ.

Tuy nhiên người dân Việt luôn luôn gắn bó sâu đậm với đất nước khiến họ không nhường bộ trong cuộc đấu tranh vì thế theo sự suy luận của một nhóm người, họ là những kẻ đi chinh phục tàn nhẫn và đáng sợ nhưng còn nhóm người khác thì họ là những người bảo vệ chính đáng trong công cuộc chiến dành lại độc lập và tư do. Dù sao họ đã hy sinh quá nhiều trong quá khứ về sinh mạng cho hai khái niệm: độc lập và tự do mà họ không có quen để lựa chọn hay tách biệt. Chính vì vậy họ vẫn trong tình trạng khổ tâm không ít. Rồi họ cũng có lần lượt hai khái niệm nầy với cái giá mạng người quá đắt. Việc ý thức tập thể bất đầu thành hình qua nhiều năm với Nguyễn An Ninh.

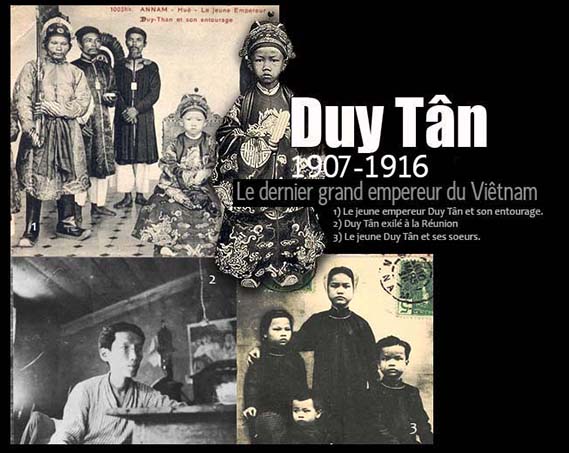

Mặc dầu ba vị vua trẻ Việt Nam Hàm Nghi, Thành Thái và Duy Tân bị lưu đày ở Algérie và La Réunion và việc xử trảm nhiều nhà cách mạng trong đó có một chàng trai trẻ tài ba Nguyễn Thái Học, người dân Việt vẫn không mất nhuệ khí trong các cuộc nổi dậy và dành lại độc lập với chiến thắng ở Điên Biên Phủ vào năm 1954. Việc thả ba trăm tấn bom (265 kí cho mỗi người dân Việt) và 60 triệu lít chất làm rụng lá cũng không làm nản lòng người dân Việt trên con đường thống nhất lại đất nước với sự sụp đổ chính quyền Saïgon vào năm 1975 sau đó dẫn đến việc đày biết bao nhiêu người lính miền nam đến trại học tập và cuộc di tản chưa từng thấy, có rất nhiều người thuyền nhân chết đuối và bị hảm hại bởi hải tặc ở biển Đông và vịnh Thái Lan để đi tìm tự do.

Theo lời tường thuật của nhiều tác giả Tây Âu, (Barry Wain, Magali Barbieri) có dịp nghiên cứu về vấn đề nầy thì có ít nhất tổi thiểu là 250.000 người Việt vượt biên chết ở biển. Theo sự dự tính của cơ quan HCR (Haut Commissariat pour les Réfugiés), từ 1975 đến 1991, trong 16 năm, có gần một triệu người dân Việt mà trong đó có 8 trăm nghìn người di tản đã lìa bỏ Việt Nam. Con đường hòa giải dân tộc rất còn xa vời vì nó đầy gian nan, cạm bẩy và vụng về sau ba thập niên chiến tranh và đau khổ.

Một trang lịch sữ đã khép lại nhưng Việt Nam phải trả giá rất đắt không những trên phương diện con người và môi trường bởi vì vẫn tiếp tục nhận những hậu quả không ước lượng nổi của bao nhiêu thập niên chiến tranh (chất độc da cam chẵng hạn). Theo tờ báo thông tin của Unesco ghi lại tháng năm năm 2000, một tổ chức làm việc dưới sự bảo hộ của Liên Hiệp Quốc, ước tính có một phần năm rừng ở miền nam bị hủy hoại bởi các thuốc diệt cỏ của Hoa Kỳ.

Người trai nước Việt ngày nay không biết hận thù và cũng không có nỗi buồn chiến tranh của nhà văn Bảo Ninh. Nhưng thách thức nghèo đói vẫn còn rình rập đeo đuổi. Bóng ma chiến tranh nó vẫn còn đó theo dòng ngày tháng ở biển Đông với các đảo Hoàng Sa bị cưởng đoạt năm 1974 và Trường Sa gần đây bởi người phương Bắc mà mối đe dọa càng ngày càng quá khiêu khích. Trước tham vọng quá đỗi của Trung Quốc, bài thiên sữ thi « Nam Quốc Sơn Hà » của tướng Lý Thường Kiệt phá Tống bình Chiêm, khẳng định lại chủ quyền của Việt Nam, nó trở lại ám ảnh tâm trí và vang âm trong trái tim của người con Việt.

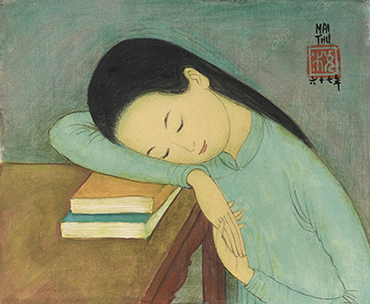

Tuy rằng với bao nỗi lo âu và cuộc sống quá tồi tệ, không ai có thể quên đi được mãnh đất nầy mà người con Việt thường gọi là Quê Hương vì chỉ ở nơi nầy có thể tìm lại kỷ niệm của tuổi ấu thơ, mái trường xưa, nguồn gốc và quá khứ. Mặc dầu mãnh đất nầy nó đồng nghĩa với chữ nghèo nàn và khổ cực, nó là lý lẽ sống đấy vì ông cha ta tranh đấu và giành được từ khi lập nước với mồ hôi, nước mắt và xương máu. Cũng như mẹ, mỗi người con dân Việt chỉ có một người mẹ duy nhất trong đời không ai có thể thay thế được. Ngoài làng ra, hình ảnh đình làng, con trâu, nón lá hay cây tre không bao giờ xoá mờ trong kí ức tập thể của người con Việt cả. Đối với những người con Việt viễn xứ, đây chỉ là một khoảng thời gian tạm thời thôi chớ nó không phải là một kết cục chính. Hình bóng Quê Hương nó vẫn đeo đuổi mãi họ như chiếc đòn gánh trên vai của người bán hàng rong với biết bao nhiêu trìu mến và luyến tiếc.

-

- Tàn tích của chế độ mẫu hệ của tộc Việt.

- Anh Cả anh Hai

- Đi tìm nguồn gốc dân tộc Việt

- Văn hóa Việt có phải là bản sao của văn hóa Tàu không?

- Tại sao Việt Nam không bị đồng hóa bởi người Hoa?

- Chim Lạc có phải vật tổ của người dân Việt không?

- Giải mã những thông điệp mà người Việt cổ để lại trong truyền thuyết.

- Nam Tiến: sự kết thúc nước Chiêm Thành (Fin du Champa)

- Tục lệ thờ cá Ông (Le culte de la baleine)

- Làng Việt Nam (Village vietnamien)

- Thiền Tông Việt Nam (Le zen vietnamien)